‘Greek fever’ at the Gennadius Library

It may be lacking the glitz and glamour originally envisioned before the pandemic, but the bicentennial of the 1821 Greek Revolution has already served its true purpose by activating a new, more incisive exploration of the country’s past through the prism of the greatest event to define the modern Greek state.

Scientific research into that era has been significantly bolstered and archives delved into to reveal new treasures, though the majority of the many exhibitions organized on the subject have so far only allowed us a brief, remote glimpse into their material. Others are expected to open their doors to the public when restrictions are lifted. These include a show announced recently by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, titled “The Free and the Brave: American Philhellenes and the Glorious Struggle of the Greeks (1776-1866).” Its opening at the Makriyannis Wing of the Gennadius Library has been slated for May 25, but the show will also be available online, according to the ASCSA.

The Gennadius Library’s collection on 1821 contains a wealth of rare publications, pamphlets, memoirs, newspapers, archival material, engravings, travelogues, maps, poems and textbooks that are well-known resources for the history of the Greek Revolution and Philhellenism. Curated by director Maria Georgopoulou, this exhibition is dedicated to American philhellenes and their efforts to convince the public in the United States that Greece, as the birthplace of democracy, deserved to be reborn as a free and independent state. The passion with which many Americans started collecting money, clothing and food in aid of the cause was dubbed “Greek fever” and provided immense relief to the civilian population in war-torn Greece, but also to the newly founded Greek state a few years later. The documents presented in the exhibition are unique and rich in information. With their help, we can unearth precious historical evidence.

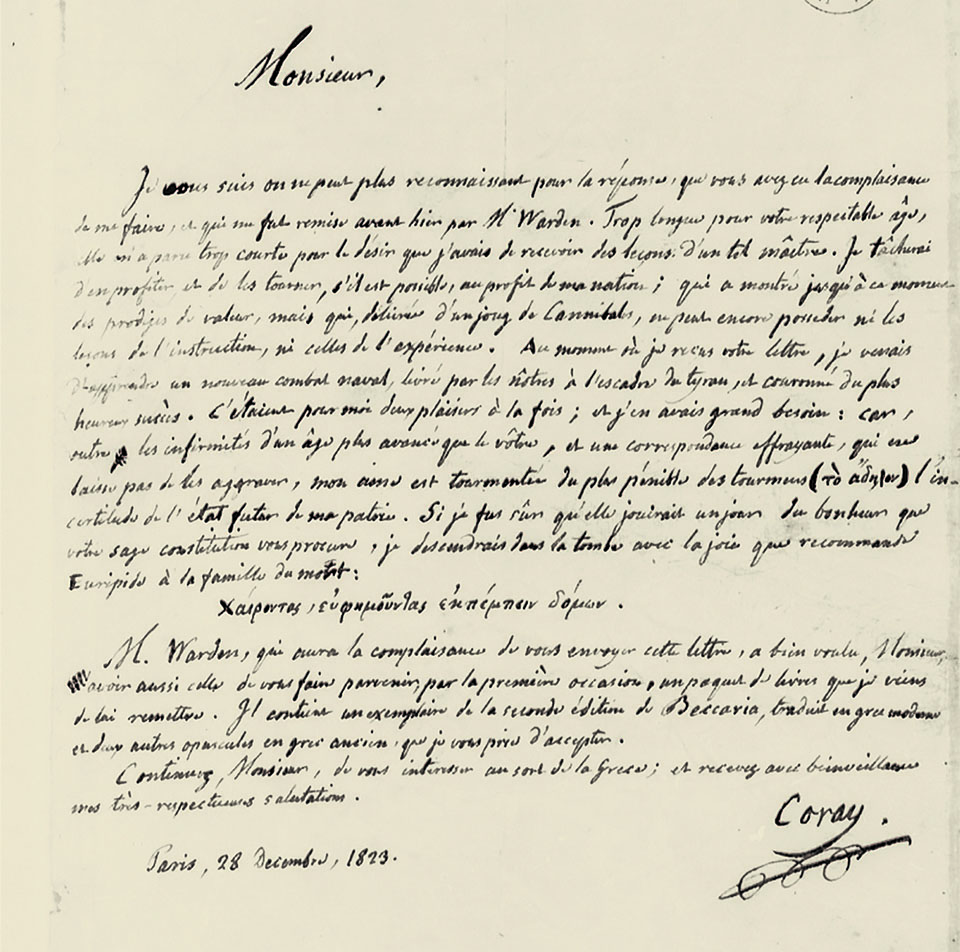

Correspondence

Adamantios Korais, the most significant intellectual of the Greek Enlightenment, envisaged a democratic Greece that would restore the glory of Pericles’ Golden Age. In the process of formulating his political plans, in 1823 he exchanged ideas on the Greek Revolution and the Constitution with the father of American democracy, Thomas Jefferson, who had a strong background in Classical studies. Jefferson also owned a large number of works and translations by Korais. The Classical education and study of Hellenism that flourished in the 18th century in Europe and the US was expressed mainly through literature, art and architecture, and created fertile ground for the support of the Greek revolutionaries. In their correspondence, the two men exchanged views on the War of Independence and the Constitution. Although brief, their communication offers a rare record of the advice given by a state founder to a scholar who dreamed of a new Greece. Korais’ first letter to Jefferson is dated July 10, 1823. The latter responded with a “Letter to Mr A. Korais, October 31, 1823.”

The hero doctor from Boston

Samuel Gridley Howe, a 19th century American physician and abolitionist from Boston, was the most important of the American philhellenes. Immediately after graduating from Harvard in 1824, he came to Greece. He enlisted with the Greek revolutionaries and for six years served as a soldier and chief surgeon. In 1827 he returned to the US to take over the administration of the Perkins School for the Blind, but remained forever devoted to Greece and its struggle. He managed to raise about 60,000 dollars, which he spent on supplies and clothing. When the region of Corinthia was liberated, Howe established a model rural community in the village of Examilia, which he named Washingtonia, and financed the construction of a supply depot to relieve nearby refugees. In 1866 he returned to Greece with his wife to support the Cretan uprising.

‘The Greek Slave’

Hiram Powers was one of the first American sculptors to gain international recognition. He reached the peak of his fame in the late 1840s with “The Greek Slave,” a life-size marble sculpture depicting a chained naked woman. Born on a farm in Vermont, the artist moved to Florence, Italy with his wife and young children in 1837, to develop his art. He set up a studio, where he divided the work between his many assistants, and used the latest technologies to accurately reproduce many copies of his most popular designs in marble. “The Greek Slave” evolved into the most famous sculpture of the 19th century and established Powers as an international star.

He justified the absolute nudity of the sculpture by claiming that his work depicted historical events: A Greek woman who was captured by the Ottoman forces during the Revolution was stripped naked and chained to be sold at a slave market in Istanbul. The work was almost immediately associated with the anti-slavery struggle in the United States, where proponents of the struggle used images of the statue to further their cause. The sculptor created six life-size marble copies of “The Greek Slave,” each of which was considered an original work of art. To his great disappointment, the sculpture was so popular that countless imitations were made without his approval.

“The Free and the Brave: American Philhellenes and the Glorious Struggle of the Greeks (1776-1866)” will be on display at the Gennadius Library’s Makrygiannis Wing from May 25 to December 19, 2021.