We owe the lost children justice

In war, poverty and clashes of civilizations, women and children are as much on the frontlines as are the protagonists, the soldiers. But their stories usually remain untold. Dark wounds mark souls and societies, forgotten, allowed no release through catharsis, atonement, personal and national salvation.

A few weeks ago, the unmarked graves of at least 600 children of Canada’s First Nations were found in a field. They were boarders at a Catholic Church residential school (since closed), buried without tombstones, nameless. A month earlier, another 215 had been found in a mass grave at another former school. From the 19th century to the 1970s, some 150,000 children of First Nations tribes were torn away from their parents and their traditions in an effort to “civilize them,” to raise them in European ways. In Catholic Church boarding schools they were often victims of criminal activity and hardship. Many died, far from their families. A similar campaign of cultural eradication (genocide) was waged in Australia from 1912 to 1962. In other countries, such as Italy and Ireland, the church took into its homes orphans, foundlings and “illegitimate” children in an effort to “reform” them.

They, too, suffered every kind of physical and psychological abuse; their stories, too, were buried in silence and darkness, until they were revealed in our more compassionate time. (This is not written in irony: Despite our era’s many problems, never have so many people cared about the fate of so many others, unknown to them, in other lands, in other times, as they do today.)

In Greece we are well aware of how children have been victims of politics through the ages. The “gathering up” of children during the Ottoman era and in the Civil War is carved deep into our collective memory and remains the subject of impassioned discussion. On a smaller scale, but no less traumatic (and with political roots, too), is the story of more than 3,000 children, who, at the height of the Cold War, were sent to the United States for adoption. This was the first mass instance of a phenomenon which we now identify with poor countries in Asia and Africa.

Some adoptions were the product of crime, when unmarried mothers were told that their newborn had died, while a network of middlemen shipped the baby away for adoption. Most of them, though, seem to have been the product of the political climate of the time, which encouraged the adoption of Greek children by American couples. Many Greek Americans (and others) wanted children, whereas in Greece there were many orphans and foundlings in institutions. The “pull” from the West’s leading power and the “push” from its troubled ally encouraged the establishment of a black market for infants. In this way, many were adopted without the correct procedures, with no one caring what became of them.

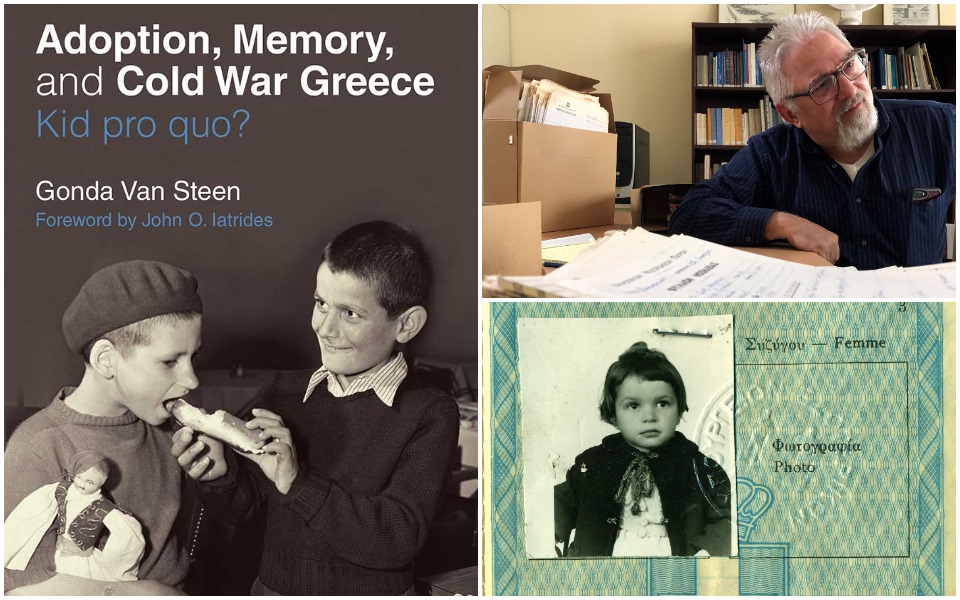

In “Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece: Kid pro quo?” (University of Michigan Press, 2019), Gonda Van Steen presents and analyses this complicated issue through meticulous research, through many interviews with adopted children, through a thorough understanding of the period and sources, with great compassion for the children and their mothers. This impeccably sourced and sober narrative sheds light on all the aspects of a shadowy tale that took place during one of Greece’s most difficult periods.

I have followed this story since 1995, initially as as reporter for The Associated Press, when I met with some of the adoptees (who were middle-aged by then), who came to Greece seeking their roots. They had been cut off violently from their families and the networks that are so important in our culture. Some had landed up in unsuitable homes and had difficult lives. Others grew up in loving households but still had a strong sense of loss. When they tried to reconnect with their roots in Greece, some found mothers and families, others ran into a dead end. What is most moving now is that many of the adoptees who are trying to gain citizenship of the country in which they were born have run into the familiar wall of bureaucratic malevolence and indifference that defines the Greek state at its worst.

Van Steen, who holds the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature at King’s College London, and Mary Cardaras, associate professor and chair of the Department of Communication at California State University, East Bay, who was adopted from Greece to the United States in the 1950s, wrote about this recently. They propose that Greece cut through the red tape, summon its “lost children” and give them their Greek citizenship.

“A nation comes out stronger when it acknowledges its historic mistakes, does what it can to correct them, and embraces any members of its society, including the most innocent of its former citizens: ‘illegitimate’ children, foundlings, undesirables,” they wrote in pappaspost.com.