A treasure of the Vlachs comes to light

Archive offers a glimpse into little-known aspects of the Balkans’ human geography

“Mr Ambassador, please accept these photographs of my father Miltiadis Manaki, which come from my private collection. My father thought of himself as a Greek, and for this reason I offer these photographs for publication in the album dedicated to him.”

So read a letter from October 15, 1998 that accompanied the generous donation of an invaluable collection of photographs by cinema pioneers Yannis and Miltos Manakis. It was addressed to Greece’s ambassador in Skopje, Alexandros Mallias, and signed “Leonidas Manakis, son of Miltiadis.”

“I first met Leonidas Manakis, the police chief of Kumanovo [in what is today North Macedonia], in early 1997, together with two close associates. We spoke for eight hours. It was an unforgettable night, for all of us. He poured his heart out – something that wasn’t easy back then – and we listened to all the things that the Greek-speaking Vlachs had been yearning to say after 50-plus years of silence. Leonidas Manakis then confidentially handed me a box containing dozens of previously unpublished photographs from the private collection of his father, Miltiadis [Miltos], on the condition that they would not be made public before his death,” Ambassador ad Honorem Mallias tells Kathimerini.

Keeping up his end of the bargain, the respected diplomat waited until after Leonidas Manakis’ death to hand over the collection of the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle (MMA) in Thessaloniki, northern Greece. “It never crossed my mind to use the album in some way privately. The collection belongs to the Greek people; it was not handed to me as Alexandros Mallias but as a representative of Greece during a sensitive time. I had the good luck to have worked with the people at the MMA for decades in the diplomatic field in the Balkans. I know their work and I am absolutely confident that the archive will be put to good use and become an asset for Greece and the Balkan region,” says Mallias.

Apart from fulfilling his commission from Manakis, however, Mallias also donated his own private archive to the museum. It includes newspapers from North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Kosovo dating back 30 years, with articles on economic and political developments in the Balkans, relations between those countries and Greece, Greek policy in the Balkans and more.

Mallias was Greece’s first diplomatic envoy in Skopje after the signing of the interim accord formalizing bilateral relations in September 1995. One of the first things the embassy did was to create a register of the Greek-speaking Vlachs (also known as Aromanians) in the area.

“That is when I met Leonidas Manakis. As I delivered the box to Greece, I felt the vision behind [filmmaker] Theo Angelopoulos’ ‘Ulysses’ Gaze,’ where the fog-shrouded port becomes the reason for a reel of undeveloped film in a box to be brought out of oblivion,” he says.

Today, the box Mallias was handed is offering the public a glimpse into little-known aspects of the Balkans’ human geography in the exhibition “Yannis and Miltos Manakis: The Faces Behind the Lens,” which has been inducted into the 8th Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, whose overarching theme is, quite appositely, “Geocultura.”

‘The community’s sense of cohesion and solidarity served as the link in the shaping of a distinct code that united them and set them apart from other ethnic groups in the Ottoman Empire’

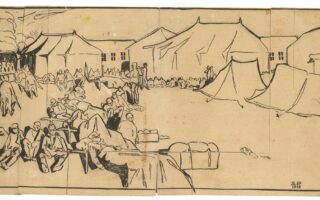

The archive left behind by the Manakis brothers – pioneers of Balkan and Greek cinema – consists of more than a hundred photographs. From rural to urban life in the big Balkan cities of the Ottoman Empire, they capture the day-to-day toil of laborers, moments of rest and fun, architectural landmarks, and historical and social events that signaled the massive changes taking place in the first half of the 20th century.

“In what was a very difficult time for the Balkans, the Vlachs managed to be one of the most powerful ethnic groups in the region. The day-to-day life of livestock farmers and merchants was a constant struggle. Despite the constant relocations, the community’s sense of cohesion and solidarity served as the link in the shaping of a distinct code that united them and set them apart from other ethnic groups in the Ottoman Empire,” says Stavroula Mavrogeni, a professor at the University of Macedonia and head of the Research Center for Macedonian History and Documentation, but also co-curator of the exhibition, along with Fani Tsatsaia, managing director of the Macedonian Struggle Museum’s Foundation (IMMA).

Visionary artists

Yannis and Miltos Manakis (or Manachia) were born into a family of livestock farmers in the village of Avdella in Grevena, West Macedonia, on May 18, 1878, and September 9, 1882, respectively. Despite such humble beginnings, they earned renown as cosmopolitan visionaries. Academically and artistically minded, Yannis attended a Romanian school and bought his first film camera with his brother in London.

“Their first reels were not shot in England or in Romania, but in their homeland, in Avdella,” notes Mavrogeni. It was there, in a remote spot of the Grevena mountains, that they shot “Yfandres” (Weavers) in 1905, which went on to be the first step in a brilliant career in photography and cinema.

“The images illustrate economic and social life, local modes of dress, education and the role of women at the core of the family in a male-centric community, the propagator of Vlach morals, education and language, which may convey a sense of ‘ghettoization’ yet safeguarded a cultural treasure,” adds Mavrogeni.

After setting up their first photography workshop in northwestern Ioannina in the early 20th century, the brothers then moved to the Greek town of Monastir (present-day Bitola in North Macedonia), where the opened a photography studio and movie theater after the end of World War I.

Identifying as Greeks, they wanted to return to Greece after the state was formed. Yannis managed to return, moving to Thessaloniki in 1939 and living there until his death in 1964. Miltos became “trapped” in former Yugoslavia, but still maintained very strong ties with his family back in Avdella. He was honored for his contribution by Josip Broz Tito and died in Monastir at the age of 82 without having realized his dream of living in Greece again.

Their ethnographic observations, captured in their collection of thousands of photographs and films – the bulk of which is in Monastir – are a priceless legacy for modern history and for the people of the Balkans.

“Yiannis and Miltos Manakis: The Faces Behind the Lens,” is at the Museum of the Macedonia Struggle (23 Proxenou Koromila, Thessaloniki; biennale8.gr) through December 31.