Nikaia, back when it was Nea Kokkinia

Two exhibitions at the municipal library of the Piraeus suburb pay tribute to the refugees from Asia Minor and their photographers

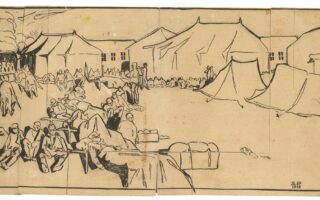

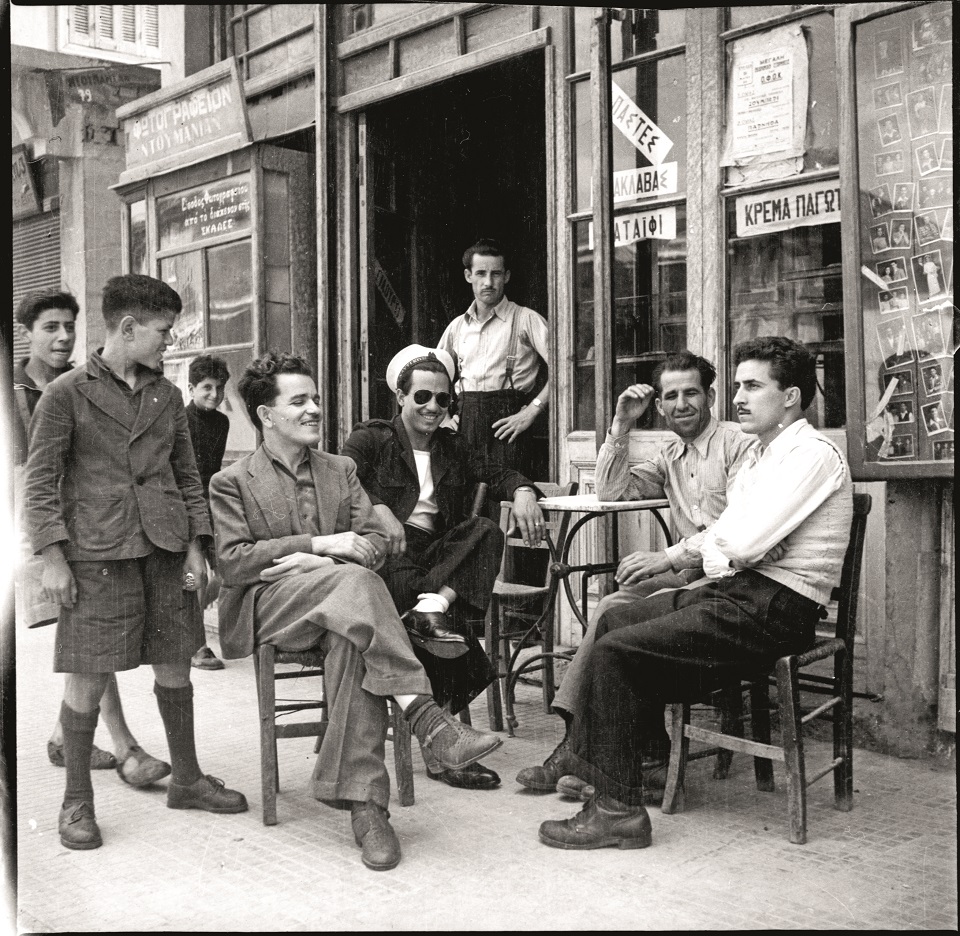

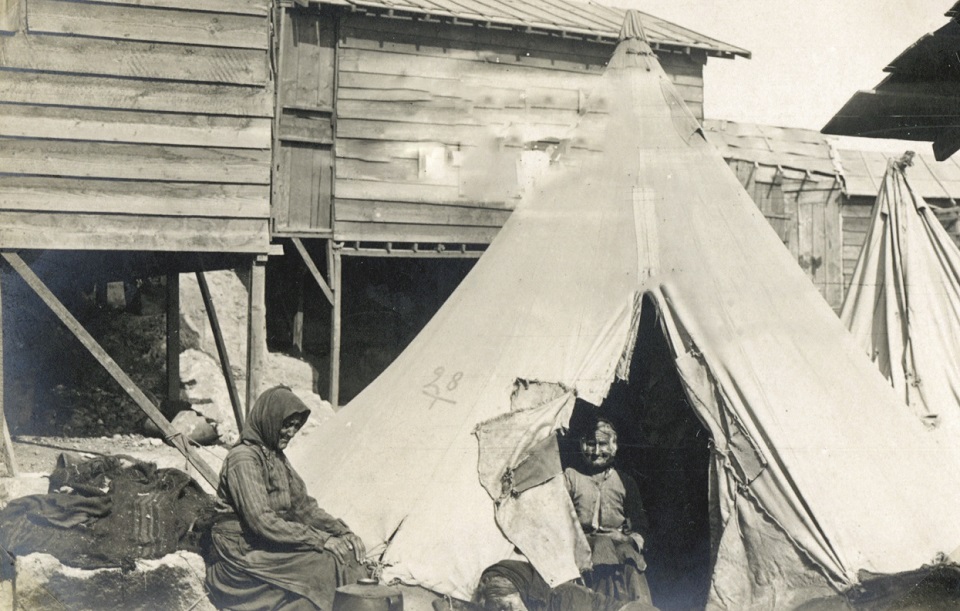

Young women just arrived from Asia Minor learn to sew; two refugees from Mugla get married; five men pose for a photograph in front of a painted backdrop. These and many more scenes captured by the photographic lens offer insight into the day-to-day lives of thousands of refugees who settled in Nea Kokkinia, the present-day Piraeus suburb of Nikaia, after the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe and the 1923 population swaps. At the same time, a wealth of archival material, works of art, traditional clothing, personal heirlooms and written material on those who moved into the settlement breathe life into the area’s history.

These important historical archives on the biggest urban refugee settlement in Attica are being presented through May 19 at the Nikaia Municipal Art Gallery. Split into two – the first on the refugee settlement and the second on its photographers – the shows were inspired by the 100-year anniversary of its establishment. “The anniversary and the publication of my book are what prompted the thought of organizing a historical exhibition with different mementos, heirlooms, physical objects and photographs,” history researcher Kyriaki Papathanasopoulou, author of “The Refugee Settlement in Nikaia: Associations, Identities and Memories,” tells Kathimerini.

The first exhibition, which is based on her research, examines how the refugees began to assimilate into their new surroundings, what they did on a day-to-day basis, as well as their cultural characteristics. “It looks at the arrival of more than a million refugees in Piraeus, the reactions this caused and the new situation that developed,” says Papathanasopoulou.

It also explores the various associations that emerged, mainly on the basis of where the refugees came from, and their importance in addressing the challenges of housing, employment and other practical issues. The chief purpose of these associations, says the academic, was to “help the refugees become citizens and to get the papers they needed to conduct transactions with the Greek state, as well as to help them overcome bureaucratic obstacles, one of which was the fact that many of these refugees only spoke Turkish.”

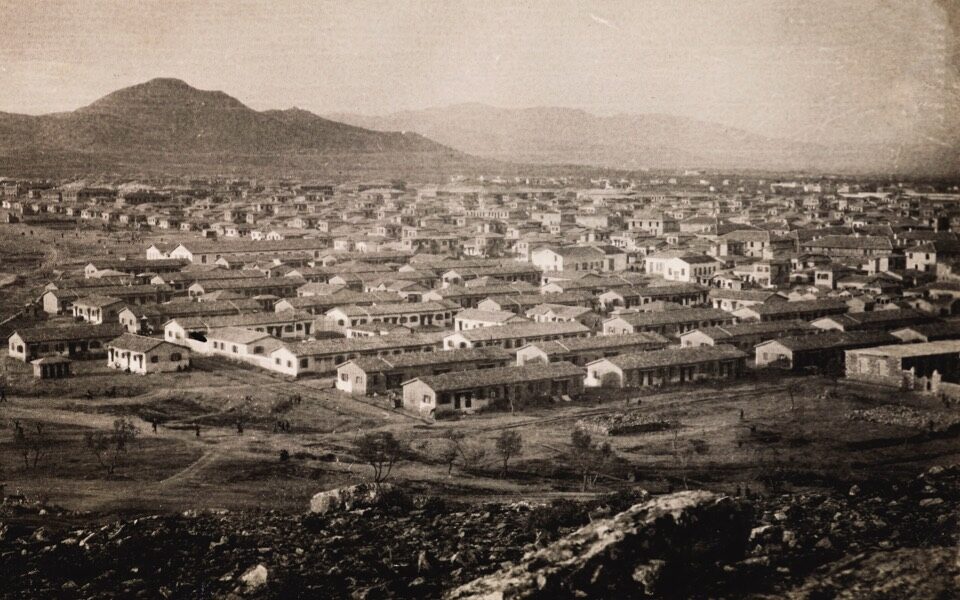

The establishment of the biggest urban refugee settlement in Attica – with more than 30,000 residents hailing from many different parts of Asia Minor – in 1928 and its gradual modernization and expansion makes up the third part of the first show. “The neighborhoods that emerged tended to have distinct ethnocultural characteristics and reflected the refugees’ reminiscences of the places they left behind. Each also had a distinct social, economic and class status,” explains Papathanasopoulou.

Improving standards

The unit “Reparations and Accommodation” focuses on how the refugees worked together to create a new town and to raise the standard of living at the neighborhood level through “beautification” associations. “They showed solidarity in order to improve their day-to-day lives, consistently making demands of the local administration or the state for infrastructure, education and schools,” says the historian.

Last but not least, there is a special unit on the refugees’ political, professional/economic assimilation into Greek society. Most of Nea Kokkinia’s residents were working class and by May 1936 were organized into active unions. In their spare time, the men played soccer, the most popular sport in those days and one for which they almost immediately created clubs upon arrival in Greece or continued those they had in Asia Minor. Associations for women began appearing in 1930. “It was important for their emancipation. This was a time when women’s identity was changing, especially as they had to work to support their families,” says Papathanasopoulou. In terms of music, rebetiko flourished in these working-class neighborhoods, “because it related to the experiences of the refugees, to their hopes and their struggles for survival in their new homeland,” she adds.

Titled “Nikaia’s Old Photographers,” the second exhibition has been curated by Maria Poulou, an art historian who is responsible for the municipal gallery. It comprises 130 shots taken by 25 photographers with links to the refugee settlement: professionals with studios in the area, known and unknown outdoor photographers and a few standout amateurs. Much of the material was brought together thanks to the significant efforts of photographer and researcher Vassilis Vasileiadis, a Nikaia native with family roots in Asia Minor.

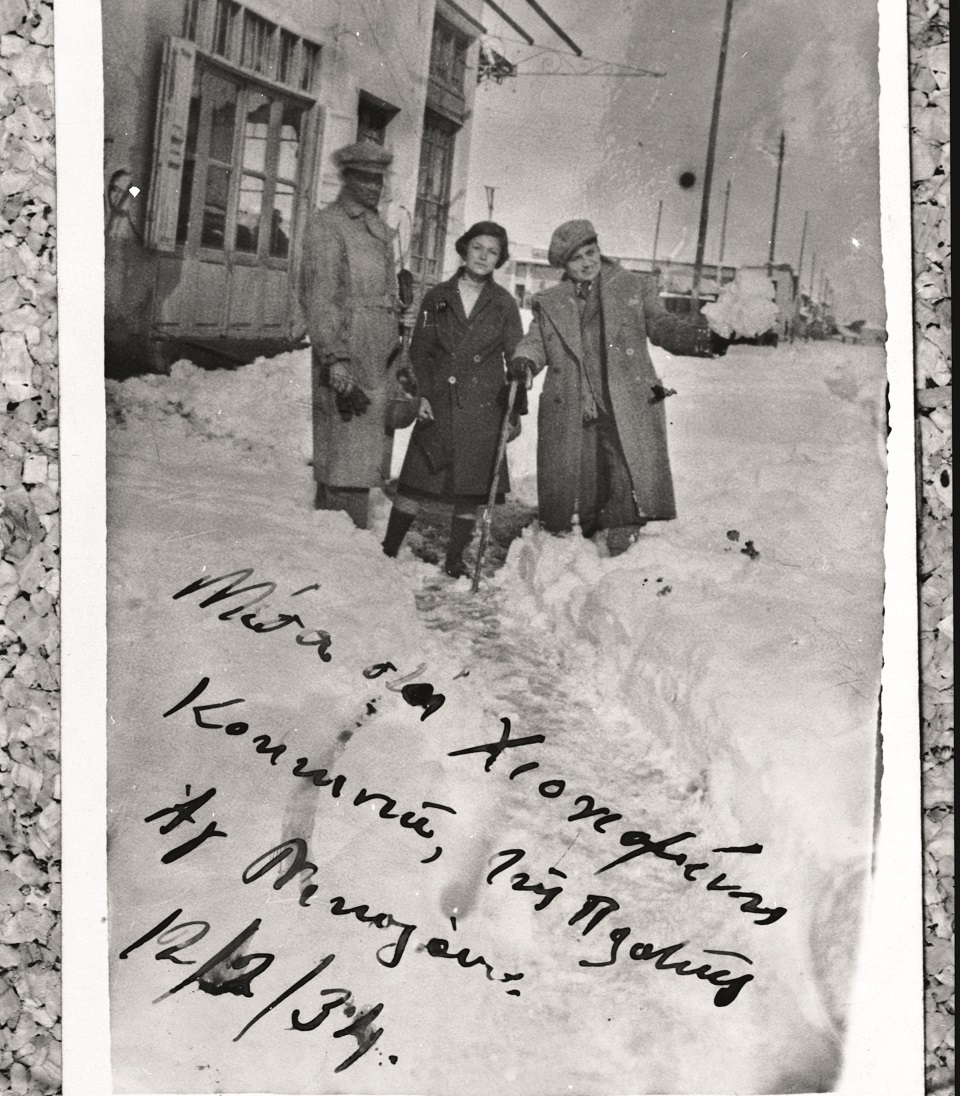

It covers the period from 1923 to 1960, meaning that it also addresses the later settlers of Nikaia, mainly internal migrants from Epirus, the Peloponnese and the Ionian island of Kefalonia. The images capture the town as it evolved, what its residents did for a living, for culture or for sport, their social interactions and events, and school and family life.

Kathimerini asked the curator what the most interesting element about the first-generation refugee photographers was. “Up until 1945, the vast majority of the photographers [in the area] were from Asia Minor and those who had been born before 1900 had trained there too. They stand out for their outstanding technical skills, but also their good taste,” explains Poulou, who sees this as evidence of the broader cultural experiences these refugees had in Asia Minor, where photography as an art form had evolved quite significantly in its ports, cities and commercial centers. Papathanasopoulou’s research, meanwhile, revealed that Nea Kokkinia’s commercial photographers set up an association called Pheidias, though no charter has been found. “The name tells us that the photographers of Nea Kokkinia were aware of their own artistic merits, and this is how they established that,” she says.

Missing monument

The refugee settlement of Nea Kokkinia may have grown and evolved into present-day Nikaia – a thriving suburb of roughly 83,000 residents – yet, as the photographer and researcher Vassilis Vasileiadis, who contributed extensively to the exhibition, says, the town has no monument marking its roots.

“Disease, poverty and hunger claimed a lot of lives in the first few years of the refugees’ settling in Nea Kokkinia. Knowing this and having lived in this town myself, I feel that there is an unpaid debt to those people who suffered and to those who died,” he says.

“This town needs to set an example; it needs to present some work of art, some installation, dedicated to the people who built it.”

Nikaia Municipal Art Gallery, 30 Redestou & Tsaldari, tel 210.491.3588, www.pinakothiki-nikaiarentis.gr