Deep dive into shipping history off Greece’s Kea island

Kathimerini speaks with members of the internaitonal team unlocking the secrets of the Britannic, the biggest ocean liner wreck in the world

On the night of April 14, 1912, the Titanic plowed into an iceberg on its maiden voyage, sending 1,500 souls to the bottom of the icy North Atlantic. Ill-fated, impressive and legendary, it became a powerful naval symbol in the collective conscience, the archetype of luxurious early 20th century sea voyages and of the burgeoning commercial competition for the Europe-America route. But the Titanic also had two sisters, the Olympic and the Britannic, which are much less known.

The White Star Line, the ships’ British owner, had planned to build three identical, ultramodern massive ocean liners that would signal the launch of a new category of passenger ship, dubbed Olympic class. The first two were built side by side in the shipyards of Belfast to designs by Thomas Andrews.

The first, the RMS Olympic, embarked on its first voyage in 1911 and spent 24 years serving as a warship and as a passenger ship. But the misfortune of the Titanic, launched a year later, delayed delivery of the third vessel, which was enhanced to be safer, stronger and faster.

‘Unlike the Titanic, which is a cold and dark tomb, the Britannic has something very alive, warm and colorful’

The HMHS Britannic was launched by the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast in 1914 but didn’t manage to sail a single commercial route before becoming embroiled in World War I and being requisitioned as a military hospital ship. It was painted white with red crosses on its sides, was equipped with more than 3,000 hospital beds and went into operation in its new capacity. Between 1915 and 1916 it carried out five successful missions in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean, transporting a total of 15,000 wounded soldiers. On its first mission to the Aegean, it took 3,300 wounded soldiers from Lemnos and brought them safely to England. On what was to be its final journey from Southampton to the Aegean, it sailed into a German mine in the Kea Strait in the early hours of November 21, 1916.

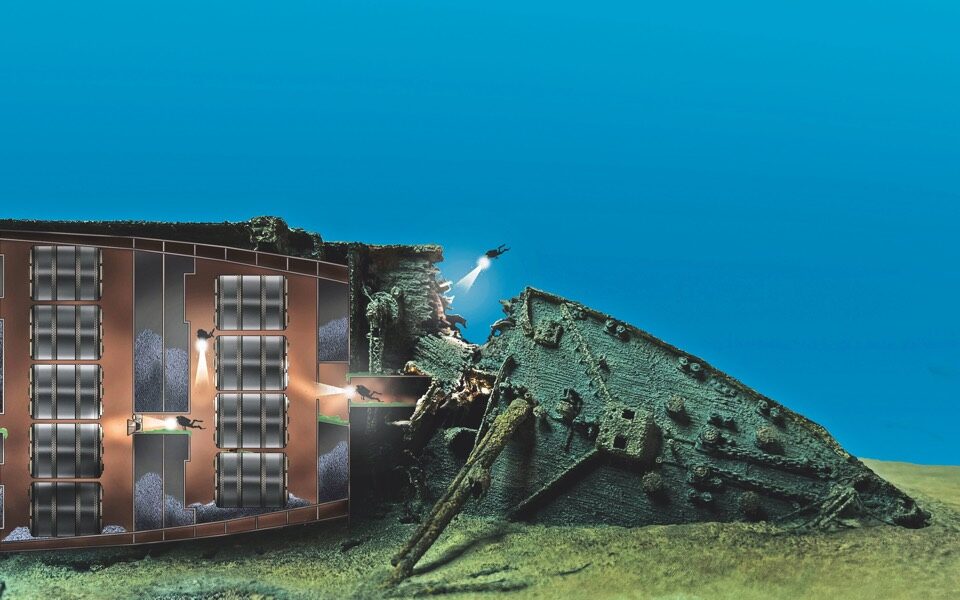

The Britannic went down in just 55 minutes, and even though the toll in lives was relatively small (of the 1,066 people on board, 1,036 survived), it did take many secrets down with it, at 122 meters below sea level. After the wreck was discovered by Jacques-Yves Cousteau in 1975, it became a “holy grail” for technical divers (a category of highly trained and experienced divers whose number does not exceed 10,000 people worldwide), with the most well-organized and professional manned research mission taking place in 2006 for the History Channel. For one of the divers on that mission, it marked the beginning of a “love affair” with the historic wreck that he says remains undiminished to this day.

American technical scuba diver Richie Kohler was actually back in Kea recently for another expedition to the Britannic, one of dozens he has carried out in the last 17 years. “My dive on the Titanic in 2005 was the occasion to begin a nearly 20-year relationship with its more beautiful and accessible sister ship. The amazing thing about the Britannic is that you can dive and touch it, swim along it or inside it. Unlike the Titanic, which is a cold and dark tomb, it has something very alive, warm and colorful,” he tells Kathimerini.

Apart from a multitude of demanding technical dives to wrecks in different parts of the world, Kohler’s resume also includes his participation as a presenter in the History Channel’s “Deep Sea Detectives” series, which was the reason for his first expedition to the Britannic in 2006. He was so fascinated by the wreck that he decided to write a book on it, “Mystery of the last Olympian.”

“The Britannic has many vestiges of her identity as a passenger ship, despite her enlistment in the war and her reconstruction as a hospital. Over the past three years our dive team has filmed – among other things – the galleys, dining and storage areas, first-class lounge, gymnasium and, more recently, the incredible interior of the Turkish baths and the ruins of the grand staircase with its glass skylight. It was fascinating to see all this after so many years of trying to access it,” he says.

Permission to access a wreck needs to be given by its owner, in this case Simon Mills, a British maritime historian and film technician, and by the Greek Culture Ministry’s Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, which has designated the area an archaeological site.

Kathimerini contacted Mills for comment, noting that the idea of a wreck being bought by a private individual may seem odd to some readers.

“Believe it or not,” he tells Kathimerini, “every shipwreck has an owner. Furthermore, warships always belong to the nation that paid for them, so every Greek warship – wherever it sinks – will always belong to the Greek government. The Britannic was a ship that sank while it belonged to the British government, so it acquired legal title to it and could transfer it, as it did in 2006 when I bought it.”

Mills is not comfortable with the description of “owner,” though, and prefers to be referred to as the Britannic’s “custodian.” His plan is to work with the diving teams to retrieve objects of historical significance contained inside the wreck. “The idea is to eventually recover a representative number of items for preservation and public display. I hope this will happen in Greece – possibly in the expected National Museum of Maritime Antiquities in Piraeus – and in the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Belfast, the city where the Britannic was built. There is also the possibility of displaying the findings in Kea, and also in other places,” he explains.

As Kohler says, “we hope that soon the [ministry] and Simon Mills can find a way to facilitate the recovery of many of these incredible items so that we can help save these unique pieces of history. And, on such a large and intact ship, there is still much to see and find. I remind you that this is the largest passenger ship wreck in the world, which is not only almost intact, but also accessible for diving.”

On expeditions to the Britannic, Kohler is flanked by a team of top professionals in the field, among whom is Evan Kovacs, an experienced technical diver and cameraman, but also an expert in digital imagers who, with his company, Marine Imagine Technologies, is on the cutting edge of underwater filming.

“What we are trying to do with our missions to the Britannic is first of all to document, and perhaps one day soon we shall no longer be able to do this, since the wreck is constantly in a state of decay and subject to deterioration,” he says. “That’s why we try to capture as much as we can, as quickly as possible, in as much resolution as possible and, if possible, with impressive images that have an aesthetic value. But it is not only magical images or fascinating stories from the past that this wreck offers us, but also a series of valuable scientific measurements and information.”

Another technical diver who took part in the recent Britannic expeditions, the experienced George Vandoros, who has also explored other wrecks off the coast of Kea, spoke to Kathimerini about this particular experience.

“The fact that I can be part of such a top team and contribute to the effort of bringing the Britannic’s story to life and shedding light on the shroud of mystery surrounding it, is something that makes me very proud. I dove into the interior of the ship for the first time recently and realized just how many areas there are to explore. I felt like a kid in a 300-meter-long playhouse who’s been told he has just 30 minutes.”

The archaeological park

A very important role for this big team on this big adventure is played by Yannis Tzavelakos, the owner of the Kea Divers center, which has been responsible for organizing all the missions since 2016.

Thanks to his contribution, too – which involved six years of back and forth with the Municipality of Kea, four ministries and several other agencies – an archaeological park was created off the island’s coast that includes not just the wreck of the Britannic, but also of the French liner the Burdigala and the 19th century Greek paddle steamer Patris.

This is the only dive park of its kind in Greece and it attracts visitors from all over the world, though mainly experienced divers. “The park serves two objectives: On the one hand, it cultivates dive tourism and, on the other, it protects the environment as fishing is banned near the three wrecks. As a result, the dive to Patris is like being at some exotic island in the Pacific, as the sea is full of fish,” says Tzavelakos.

Richie Kohler also talks about this strong human chain that has set out to slowly explore the mysteries of the Britannic, about its cohesion, dedication and enthusiasm.

“Our missions are the culmination of the effort of a small but close-knit group of people who, at great risk and expense, are willing to go where no one has gone before,” he says.

“Modern underwater archaeology began in Greece with the Antikythera device, and today it continues with the Britannic, a ship that now has the opportunity to become iconic like her sister, the Titanic, in the world’s consciousness. And she deserves it, because, like Titanic, Britannic too has many ways to teach us both about our past and our present,” adds Kovacs.