From Geneva to ancient Eretria

Pierre Ducrey, emeritus professor of archaeology at the University of Lausanne, speaks about his lifelong relationship with Greece

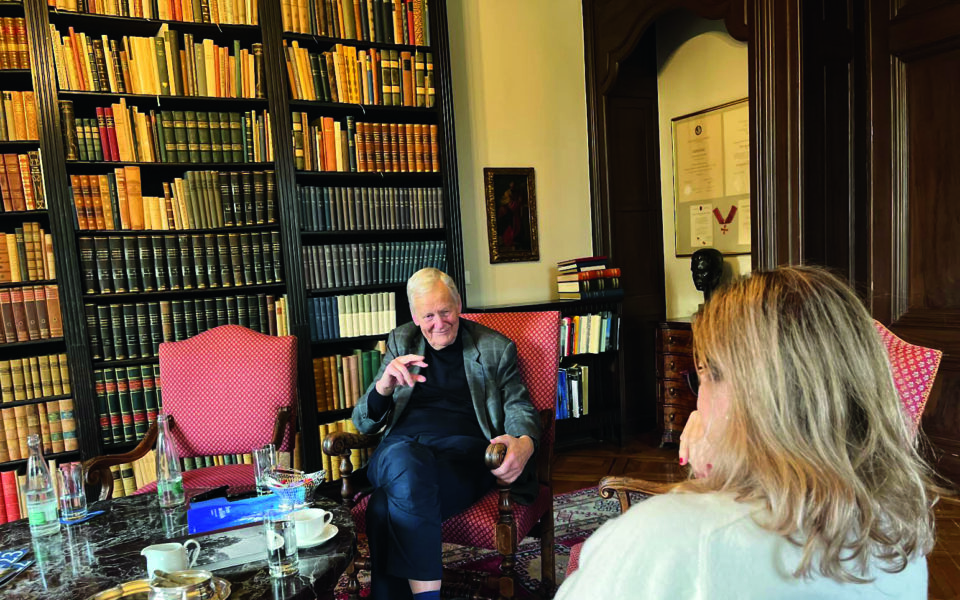

The iron gate of the villa opened automatically to let the car onto the white gravel driveway. I caught a brief glimpse of the magnificent garden, manicured to Swiss perfectionism, before seeing that Pierre Ducrey was already standing on the steps of the building that houses the Hardt Foundation to greet us with a broad smile. At 85, the emeritus professor of archaeology at the University of Lausanne is still considered the leading archaeologist in Switzerland, with an extensive scientific and teaching career. After all, he spent many years in Greece, first as a member of the French archaeological school and then head of the Swiss school – his hands have dug our soil. It is a spiritual connection so strong that it can hardly be compared to anything else, as he himself has said.

Since 2005, he has been at the helm of the Hardt Foundation for the Study of Classical Antiquity, established in Geneva in 1950 by the German Baron Kurd von Hardt. Accompanied by the Greek consul, Alexandros Yennimatas, who kindly arranged the interview, Ducrey led us through rooms with creaky oak floors, libraries filled with the nostalgic smell of old books, and settled us down in a room with a fireplace and a view of the trees surrounding the building.

“Tea, coffee? Sweet?” he asked us in fluent Greek.

“My introduction to Greece was when I was 12 and I decided to study Ancient Greek at school. Then one thing led to another and I ended up studying Classics. In 1955 my parents and I took our first trip to Greece. I saw Delphi, Corinth and Mycenae. I also went to the Acropolis when there was a full moon, and it was so bright that we were able to walk on the Holy Rock all by ourselves. Of course, there was no fence or guard at that time. It was a different time…”

I wondered aloud if that was the moment when he fell in love with Greece, the way you fall in love with a person and remember exactly the first time your heart started racing.

“No. It wasn’t just the Parthenon, but Delos, Knossos, everything I saw. Everything I’d read about in books I saw live in front of me. It was a magical image. But my love of Classical antiquity came so naturally, as if I never had a chance to do anything else in my life. And, of course, I didn’t.

“But I had to wait until January 1967, when I found myself in Athens as a foreign member of the French School. One of my first experiences was with the junta. I will never forget April 21, when I tried to go from Psychiko, where I lived, to the office in the center of Athens. Passing through Ambelokipi, I ran into the tanks! Troops were everywhere. A terrible scene for a Swiss. In those first years I worked on Crete and in Philippi [northern Greece], but beyond the history of your country, I discovered and came to love the modern Greeks.”

Unlike some foreign archaeologists who see only antiquities, Ducrey seems to have identified with the people he met, made friends with and worked with.

“Today it has been 57 long years, your homeland is a big part of my life and I have extraordinary memories. However, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. I remember in 1981, with the arrival of PASOK, they said they were going to close down the foreign archaeology schools. An official from the Ministry of Culture came to Eretria and said to me, ‘Don’t you think it’s unfair that you foreigners are digging on our land?’ I replied: ‘You are right, but maybe it would be good if I stayed and helped you. If you don’t want that, we can leave.’”

Those were difficult years. Swiss archaeologists began excavating the fragments of ancient Eretria on the island of Evia. We always said that we wanted to work for Greece, for the splendor of its history and culture. In 60 years, hundreds of Swiss archaeologists have passed through Eretria and have come to love Greece deeply, it is what I call ‘new philhellenism.’”

‘Beyond the history of your country, I discovered and came to love the modern Greeks,’ the Swiss archaeologist says

I couldn’t help but ask Ducrey what he thought about the campaign for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures.

“Of course they should come back, the Acropolis Museum is wonderful. I would add that it was also built by a Swiss, Bernard Tschumi, whose first concern was to connect the temple with the sculptures, at least visually. But perhaps we should ask ourselves why the Greeks only request the return of antiquities from the British. There are Greek treasures in other foreign museums as well.”

I listened attentively to Ducrey and noted the ability of the Swiss, for the sake of their neutrality, to distance themselves from the rest of Europe and to see things from a different perspective. The Greek side, of course, has at this stage attached the greatest importance to the reunification of the sculptures with the rest of the marbles from the Parthenon, in order to recreate an intact whole at the Acropolis Museum.

‘Greeks are more open to life’

As we talked, I looked at the paintings, the sculptures, the antique furniture that made the room of this building a unique place to study antiquity. There was an unimaginable silence, broken only by the birds singing outside. What a pity that we do not have anything like it in Greece. A place that makes you believe, as a student or a scholar, that you are dealing with something of great importance, because the very environment in which you work gives you that feeling.

Before I left, I asked Ducrey what he took away from those 57 years of interaction with our country.

“Some friendships we made with people like [archaeologist and writer] Vana Hatzimichali. In 1970, when Alexandros Panagoulis was imprisoned [for attempting to assassinate dictator Georgios Papadopoulos], [physician] Amalia Fleming and Vana’s husband [architect] Nikos Hatzimichalis tried to arrange his escape. Some members of the Greek military junta found out and arrested Fleming, but Nikos escaped. My wife and I witnessed all this and for a short time we even looked after their 10-year-old child Nikita because the situation was so difficult. But it seems that the love for Greece is hereditary. My daughter has a child with a Greek man and I have a granddaughter who is half-Greek. I am very fond of Orthodoxy, I have been to Mount Athos. Compared to our religion, Calvinism or Catholicism, it doesn’t weigh people down with the burden of original sin. I think Greeks are freer; somehow they are more open to life, they enjoy it more.

“On the other hand, this freedom may not work well when combined with a lack of law enforcement. For example, if there is a sign that says ‘No Parking,’ it will be invisible to the Greek drivers who park just below it. And, of course, no policeman will show up to give them a ticket… Here in Switzerland, we have the opposite phenomenon. If you park illegally, the citizens themselves may come to reprimand you. All the Swiss are a little bit of a policeman. That’s not nice either. Maybe perfection is somewhere in the middle, and I have been at both extremes in my life. But even so, I consider myself very lucky to have lived in the middle of this contrast.”

We take photos with Ducrey before we leave and feel with certainty that all those foreign archaeologists who have worked in Greece have been the best “ambassadors” of our history to the international community.

The excavation

Ducrey is very proud of the work of the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

After all, Eretria was one of the cities that contributed to the greatness of ancient Greece, playing a catalytic role in the spread of the alphabet and the connection with the Mediterranean world in the 8th century BC.

“When you dig in cities like this, you cannot help but be excited and thrilled by every find. Besides, I think that is the archaeologist’s reward, to be able to understand the whole course of humanity from small fragments. Eretria has been a great school for those of us who have passed through it and for the new generations of my compatriots who have the privilege of working there. In 2024 we will celebrate 60 years of presence in Greece.”