Greek theater celebrated in Amsterdam

Six productions by the Onassis Stegi and one by the NTG at the Brandhaarden Festival 2024

AMSTERDAM – Crossing the street to get to the Internationaal Theater Amsterdam (ITA), I saw three students trying to take a selfie with the image of Giannis Angelakas from the poster of “Nekyia” in the background. “Are you Greek?” I asked the young women. No answer. I repeated the question in English. “My boyfriend is Greek,” one called Eline explained. “We’re coming tonight, we can’t miss it.”

They were all university students from Rotterdam. I was not surprised that Greeks would travel from Belgium and Germany for Angelakas – frontman of the popular rock act Trypes – but I was not sure the young Dutch women would understand that what they were about to see was not a concert, but a stage adaptation of Homer. It is a choreographer directing an actress and a Greek rock musician in L Rhapsody, the darkest of “The Odyssey,” I explained. “Very interesting but it’s also very Greek to us,” they responded, laughing.

Largely unknown outside its borders, the multifaceted contemporary Greek theater scene was honored in Amsterdam recently, with six productions by the Onassis Stegi and one by the National Theater of Greece featuring at “Brandhaarden 2024: Onassis” as the full title of this year’s installment of one of Europe’s top theater festivals was.

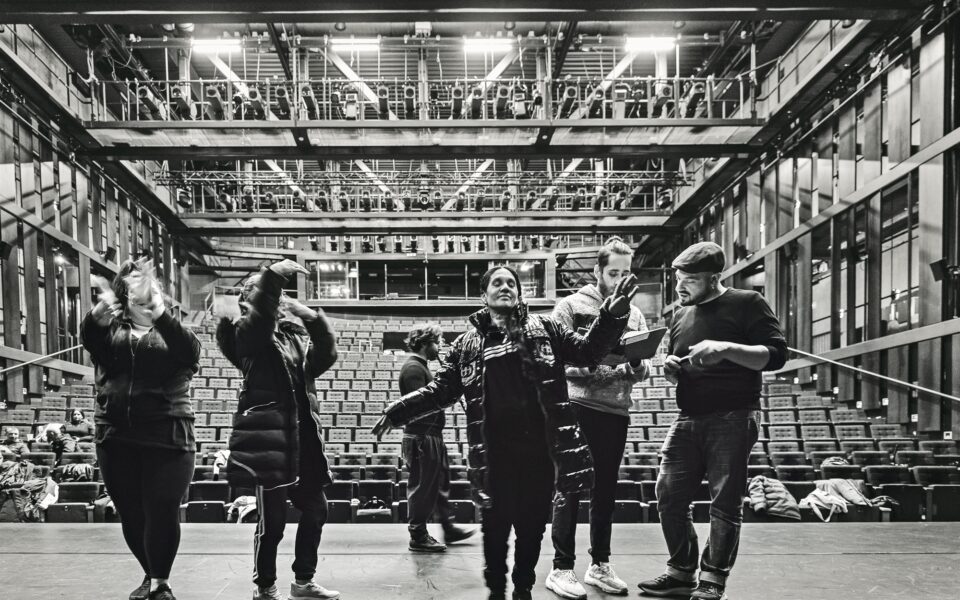

The organizers invited productions selected from a series of proposals made by the Onassis Stegi – among them Mario Banushi’s “Goodbye, Lindita,” from the National Theater of Greece, as the young director is an Onassis AiR Fellow this year – and tried to find common references with their own theater, but also to broaden their horizons, to find out what is happening in another part of the world, not so far from their own.

I met the students again in the evening, as we entered the wonderful Stadsschouwburg Haarlem theater, with its Italian stage that was built in 1894. It is the building that houses the ITA organization and where all the festival activities take place. I tried to understand the anthropogeography of the place. I saw many Dutch people of different ages who may love theater or ancient Greek culture, students communicating in different languages and, of course, many from the Greek community. The lights went out and when they came back on, the audience stood up for long round of applause.

After-talk

After-talk usually follow in one of the theater’s bars. Here, it was part of the theatrical experience. Christos Papadopoulos took the floor to explain how he came up with the visualization of Hades and Ulysses’ descent into it. There are no clues, he said laughing, so he decided to work with the most poignant cliche: darkness. “When I was a little boy being put to sleep, every sound or light had a different meaning. I could tell that a car was passing on the street by the sound of the engine and the light coming through the shutters,” he explained.

‘We are interested in the conversation between the past and the present, between tradition and the avant-garde’

An unfortunate description, I thought – the Dutch don’t have shutters – but it’s completely accurate to what he created and what we have in mind when we think of fear/horror. You can’t prove anything with logic, but you have a feeling that something has passed behind you or next to you. A woman in the audience said that it was difficult for her to follow the subtitles and the scene at the same time, and that the moment she managed to concentrate on what was happening in front of her and not worry about the translation, it was as if she was entering a studio, as if the sound was isolated and she was listening to her thoughts.

Angelakas added some food for thought: “It’s such a shame that we were driven away from these texts as students. Is there any better way to celebrate life? Newer religions have taught us to live with guilt, to expect another, better life after death. The ancients had no such distinctions, everyone went to the same place. It doesn’t matter afterwards, what we live now, that’s what matters.”

The next day I met Clayde Menso, director of ITA, and Daniel Kieft, program adviser of the 12th edition of Brandhaarden. “Why Greece?” was the first question I asked. “For us, it is more than obvious that a Western European theater organization would turn its attention to Greece. Brandhaarden wants to show what is happening internationally, and it cannot ignore Greece. It is touching that even today writers and directors are inspired by ancient texts and myths, and that the distance between yesterday and today is erased,” said Menso, defending their decision.

I noted, however, that with the exception of “Nekyia,” all the other productions (Vasilis Vilaras’ “Earthquake,” “Constatinopoliad,” “Goodbye, Lindita,” Dimitris Karantzas’ “The House,” Prodromos Tsinikoris and Anestis Azas’ “Romaland”) dealt with contemporary themes. “We are interested in the conversation between the past and the present, between tradition and the avant-garde. That’s why we collaborated with the Onassis Foundation, which promotes contemporary culture and new voices without turning its back on Greek mythology or older references. It maintains a balance and has had an extroverted orientation for years.”

‘It’s not just words’

But isn’t language an obstacle to such an undertaking? They both disagreed, pointing out that some of the performances in this year’s program were not based on words. “Theater is not just words, it’s more than that,” Kieft argued. “‘The House’ talked about climate change and the rise of the far right, issues that concern us as well, but ‘Goodbye, Lindita’ also touched a nerve, the way Mario, this wonderful boy with the maturity of a 50-year-old, portrayed loss,” added Menso. The problem is very often in references or jokes that get lost in translation, they both explained, and I’m sure they had “Romaland” in mind. What could the western Athenian district of Zefyri, known for its Roma camps, convey to Amsterdam? How could the two worlds meet? “We don’t know much about the Roma, but we also have marginal communities here. The performances must also act a bit like a magnifying glass,” Kieft pointed out.

Melpo’s night

That same evening, the seats at the theater’s new stage were filled to capacity. The show began with all the stereotypical images of the Roma: the shacks, the clarinets, the plastic chairs and all the cliches about “Gypsy” habits. Until five amateur actors took their clothes off on stage and told their stories. I was most moved by Melpo. More feminist than the feminists, militant and proud, she told the Dutch that this play was her second job, the first being as a cleaner in a kindergarten. She couldn’t read, had never gone out for coffee, had never been to the theater. At the end, she informed the audience that she had left cards with her phone number in the foyer in case anyone needed her for work.

In the after-talk that followed, the first question was about her. How many job offers had she received between the time she left her dressing room and the time of this conversation? “Lots,” she said, wiping tears from her eyes.

The next day, at a rebetiko music concert with Lena Kitsopoulou and her band, I met Kieft again. Had he finally decided how Greek theater differs from the Dutch?

“You say things directly, we say things more indirectly.”