Efficacy of shots wanes, fueling boosters debate

As tens of millions of eligible people in the United States consider signing up for a COVID-19 booster shot, a growing body of early global research shows that the vaccines authorized in the United States remain highly protective against the disease’s worst outcomes over time, with some exceptions among older people and those with weakened immune systems.

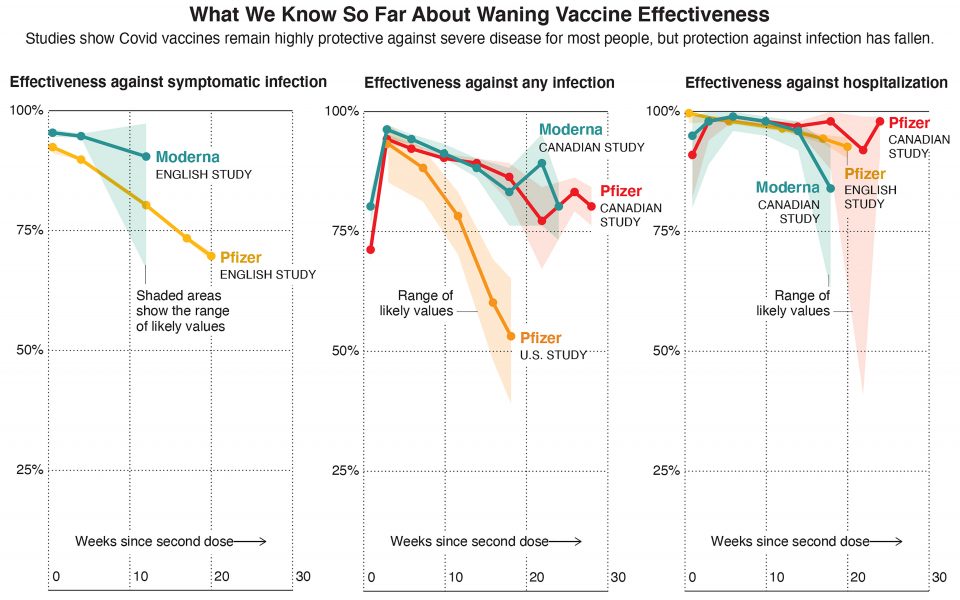

But although the vaccines’ effectiveness against severe disease and hospitalization has mostly held steady, even through the summer surge of the highly transmissible delta variant, a number of published studies show that their protection against infection, with or without symptoms, has fallen.

Public health experts say the decline doesn’t mean vaccines aren’t working.

In fact, many studies show that the vaccines remain more than 50% effective at preventing infection, the level that all COVID vaccines had to meet or exceed to be authorized by the Food and Drug Administration back in 2020. But the significance of these declines in effectiveness — and whether they suggest all adults should be eligible for a booster shot — is still up for debate.

A study in England examined the vaccines’ effectiveness against the delta variant over time. It found that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is about 90% effective at preventing symptomatic infection two weeks after the second dose but drops to 70% effective after five months.

The same study found that the Moderna vaccine’s protection also drops over time.

A study in the U.S. and another in Canada looked at the vaccines’ effectiveness at preventing any infection from delta, symptomatic or not. Although they found different levels of decline, both studies found that the vaccines’ protection dropped over time.

But both the English and Canadian studies found that even after several months, the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines remain highly effective at preventing hospitalization.

Each of the three studies showed a different rate of decline in vaccine effectiveness, which can vary in studies depending on factors such as location, the study’s methods, and any behavior differences between those who have been vaccinated and the unvaccinated. Although one of the studies has been published, the other two have not yet been peer reviewed. Still, experts say that the research generally shows trends.

“The main objective of the COVID vaccine is to prevent severe disease and death, and they are still doing a good job at that,” said Melissa Higdon, a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who leads a project to compile research on COVID vaccine performance.

But the decline in protection against infection will have an effect, she said.

“With true declines in vaccine effectiveness, we’ll likely see more cases overall,” said Higdon.

Data compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show similar trends for the mRNA vaccines, and they also suggest that the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine is less effective against severe outcomes and infection than Pfizer or Moderna.

These results have helped to shape current booster recommendations in the U.S.: Among Pfizer and Moderna recipients, those 65 and older, and adults at high risk, are eligible six months after their second shots. Any adult immunized with J&J may get a booster after two months.

Pfizer and BioNTech asked the FDA last week to approve boosters for all adults. But experts are divided over whether booster shots are necessary for those beyond the most vulnerable.

There has been more agreement among experts about the need to offer extra protection to adults older than 65. The declines observed in vaccine effectiveness for this age group may have greater repercussions, since older people face a higher risk of hospitalization.

“For those over 65, getting a booster helps cover your bases to make sure you are extra, extra protected, because the consequences are higher,” said Eli Rosenberg, deputy director for science in the Office of Public Health at the New York State Department of Health, who has studied COVID vaccine effectiveness.

Seniors are also most likely to be affected by waning vaccine immunity now, since they were among the first to be vaccinated in the U.S. About 71% of people ages 65 and older — about 36 million people — completed their initial vaccination series more than six months ago. So far, about 31% have received a booster shot.

An additional 69 million people in the U.S. younger than 65, more than a quarter of that age group, are also past that six-month mark. Not all are eligible for booster shots, although the federal government may soon decide to extend eligibility for the Pfizer booster to everyone 18 and older.

Other countries, including Israel and Canada, have authorized booster shots for all adults. Early data from Israel shows that booster shots are effective at protecting against infection and hospitalization, at least in the short term.

But experts worry that a national focus on boosters will detract from what should be the country’s most important goal.

“It’s easy with all the discussion about boosters to lose that really important message that the vaccines are still working,” Rosenberg said. “Going from an unvaccinated to a vaccinated person is still the critical step.”

[This article originally appeared in The New York Times.]