Europe’s quest to replace Russian gas faces plenty of hurdles

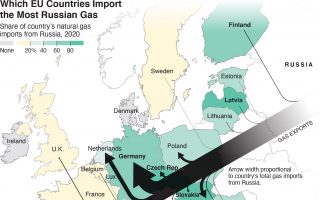

HOUSTON – Russia’s natural gas supplies have become a tool of leverage in its conflict with Europe over the Russian invasion of Ukraine. And the stakes are high for Europe, which relies on Russia for 40% of the gas that warms and lights its homes and businesses.

The confrontation also poses a challenge for the world gas market, which has generally endured less price volatility and political manipulation than oil in times of crisis.

Europe is turning to the United States to make up part of the shortfall, but fossil fuel expansion faces resistance over climate concerns and investor reluctance. Gas producers in North Africa are contending with regional political turbulence. And hopes for new gas from the eastern Mediterranean have been complicated by regional disputes and competition from Asia.

“Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has hastened the globalization of gas markets and has complicated them significantly,” said Paul Bledsoe, a climate adviser under President Bill Clinton.

Europe and Russia are already dueling over energy, with Europe moving to slash imports of Russian coal and oil. But the trade linkage is tighter for natural gas, which is harder and more expensive to ship than oil. Russia cut off gas sales to Poland and Bulgaria when they balked at demands to make payments in rubles.

Germany, Russia’s biggest European gas customer, is still buying but quickly shelved an additional Russian gas pipeline, Nord Stream 2, after the February invasion.

Gas supplies had been relatively stable since Russia briefly curtailed shipments through Ukraine in 2006. The United States, which has become the world’s largest producer and exporter, had so much gas after a boom in shale drilling that it flared off excess output, much like Iraq and other oil-rich countries that often treat gas as a waste product.

Global gas prices were rising in the months before the invasion for a variety of reasons, including diminishing hydroelectric power in Latin America because of drought and insufficient wind in Europe to propel renewables. Now, the disruption in Russian supplies has further raised prices in much of the world and increased the burning of coal.

Europe produces one-fifth of its gas needs, and its fields are in decline. The rest of its gas is imported, nearly half of which usually comes from Russia. In recent weeks, imports from Russia have declined, while Norwegian production and imports of liquefied natural gas have increased to take their place. Germany, the primary engine of the European economy, is scrambling to build expensive terminals to receive giant tankers filled with gas chilled to a liquid.

“What the invasion of Ukraine has done is take one of the three major producers of natural gas on a global basis out of the picture for future planning,” said Charif Souki, executive chair of Tellurian, a gas company building an export terminal in Louisiana. “No one will rely on Russia in the future. Now the US has the opportunity to become by far the powerhouse of natural gas.”

European countries have expressed an intention to phase out their dependence on more than 150 billion cubic feet of annual imported Russian gas, partly by importing an additional 50 billion cubic feet of LNG, roughly 50% more than they currently import.

That will not be easy, since the global LNG market is only 523 billion cubic meters a year, nearly 20% of which already goes to Europe. New LNG export terminals are coming online in the United States and Qatar, but demand is increasing even faster, especially in Asian countries trying to ease air pollution from coal burning.

That leaves the United States, even though several of its gas fields have insufficient pipeline capacity and have attracted few major drillers because prices have been so low until recently.

Since the Russian invasion, the Biden administration has pledged to increase LNG exports to the European Union by 15 billion cubic feet, or roughly 40%. That is about one-tenth of Russian shipments to Europe, but American energy experts say US companies could produce and ship much more gas with more pipelines and export terminals.

Export operations are being expanded in the United States, with three new terminals expected to be completed by 2026. An additional 10 await permits, long-term buyers and investors. EQT, a leading gas producer, has called for the country to quadruple LNG capacity by 2030, a proposal that has received broad industry support.

“We have the resources in the ground,” said David Braziel, CEO of RBN Energy, an analytics firm. “And we could develop them if you had an indication from the administration that they want to develop natural gas resources.”

But environmentalists point out that natural gas production releases methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, and warn that building a multibillion-dollar infrastructure will perpetuate carbon emissions for decades. The Biden administration has voiced support for renewables and natural gas, fully satisfying neither environmentalists nor the oil and gas industry.

“The administration is trying to have it both ways,” said Dan Becker, a lawyer at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The solution is not a short-term fix of more gas from the US or somewhere else. The solution is to switch to clean renewables.”

Aside from Russia, the Mediterranean region has become a leading gas source for much of Europe. But even as Mediterranean gas exploration has advanced, particularly in deeper waters, sales to Europe have run into nettlesome problems.

Italy has long depended on Libya for energy, even when Moammar Gadhafi ruled with ruthlessness and anti-Western rhetoric. But today, oil and gas fields and export terminals are often blocked by competing armed groups, including one aided by Russia.

Spain receives much of its gas by pipeline from Algeria, and Algeria would be happy to pump more gas to Spain and Portugal with a pipeline through Morocco, but a payments issue between Algeria and Morocco and worsening relations in general led to a stalemate in contract renewal talks in October.

Egypt has reestablished operations in two LNG terminals, exporting its own gas as well as Israel’s from their expanding offshore gas fields. China has offered such lucrative long-term contracts, however, that European buyers are finding it hard to compete.

North Africa’s gas exports to Europe fell by 5% in the first quarter of 2022 from the year before, according to Middle East Petroleum and Economic Publications, based in Cyprus.

With relations between Israel and Turkey gradually improving, energy experts say there are growing prospects for an underwater pipeline between Israeli gas fields and Turkey to tie Israeli production to European markets. But festering territorial issues between Turkey and Cyprus could slow any projects, since a pipeline would have to go through Cypriot waters. A new Cypriot gas field, called Aphrodite, looks promising, but its limited reserves will probably not flow for more than a few years.

The opportunity for gas-producing countries and states like Texas and Pennsylvania may also ultimately be limited by the environmental concerns.

Leslie Palti-Guzman, president of Gas Vista, a market intelligence company, said the fundamental shifts in the gas trade could last as long as gas prices in Europe remain high. But even though more LNG terminals will be built, she said, the future of natural gas is limited.

“Right now the US and Europe are swallowing the LNG pill, but it’s not going to last forever,” Palti-Guzman said. “Carbon neutrality is not going to go away even if currently the priority is national security.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.