Forget Halloween, bring ghost stories back to Christmas

At the most wonderful time of the year, there is one tradition that John Maguire remembers fondly: his Liverpudlian grandmother trying to scare the daylights out of him.

Without much money for Christmas celebrations, he and his family leaned instead on a centuries-old form of festive entertainment on the cold and dark evenings.

“We’d turn all the lights off, and put the candles on, and she’d tell us a story,” Maguire said. Not nice stories – ghost tales and other myths. “It used to keep me awake at night.”

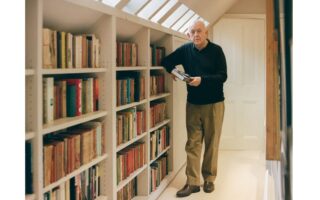

Now a grown-up, 46-year-old creative director at Arts Groupie, a group that promotes theater and other arts, he wants more people to have that painful pleasure. This year he revived the tradition, popularized during Victorian times, of sharing ghost stories at Christmas. He and other authors read chilling Victorian tales aloud to a quiet, dim library, lit by (electronic) candles.

“Dickens didn’t have the luxury of television,” he said. He still holds a belief that, at a time when green screens can manifest every potential horror, “nothing is more chilling than your own imagination.”

Christmas can be a time of cheery joy, family fun and romantic high jinks, as many a Hallmark Christmas film suggests. But if that doesn’t do it for you – Bah! Humbug! – there is another way. Perhaps your idea of a getting into the holiday spirit is the haunting of past memories, a glimpse of a specter or being driven mad by former wrongdoings.

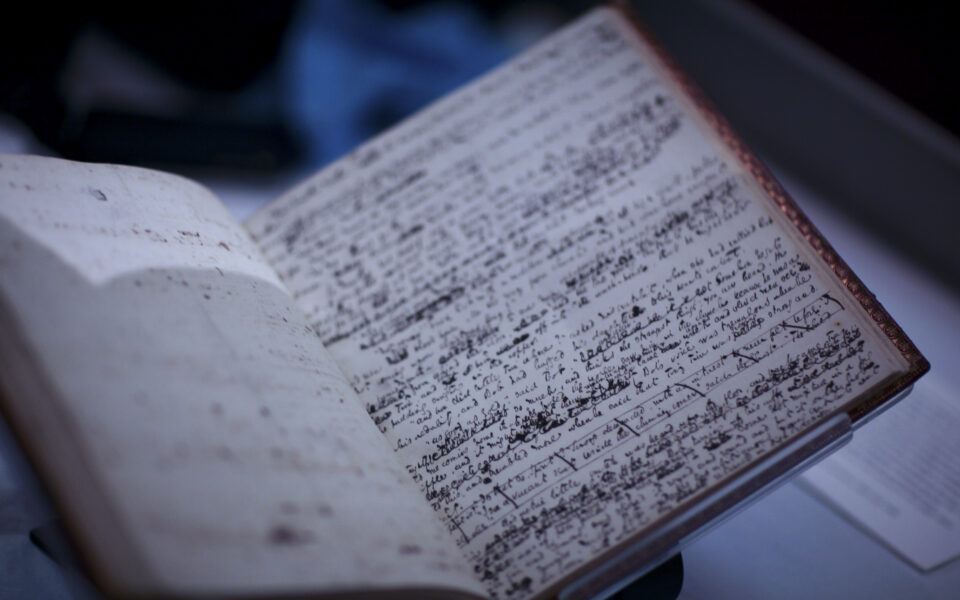

Families in Victorian England, where written ghost stories flourished in periodicals at Christmas, would have agreed. You know the most famous of them: the 1843 Dickens classic “A Christmas Carol,” in which ghosts help a miserly man change his ways. Its popularity is clear in the countless retellings onscreen and in theaters (including by the Muppets).

But his other stories, many published specifically to be read at Christmas, may now feel more appropriate for Halloween. There is “The Signal-Man” (a railway worker is troubled by an apparition); “The Haunted House” (a group of friends renting a rundown manor realize they are not alone); and “The Trial for Murder” (the ghost of a man seeking justice haunts jurors at his own murder trial).

Plenty of others have contributed to the genre, including writers such as Elizabeth Gaskell, Henry James and Montague Rhodes James. Editors populated their periodicals with stories of gothic horror, dreams and eerie events.

Though the origins are misty, experts say the tradition of telling ghost stories in the winter predates the Victorians. But mentions of the supernatural at Christmas became popular in the 19th century, as literacy rates improved and the traditions of the season as we know it were emerging – Christmas trees and cards were both introduced to Britain at the time. What else to do, on the long and dark nights as winter solstice closed in?

”The family would come together, they would play games, they would end the evening with a storytelling around the fire,” said Jen Cadwallader, a professor of English at Randolph-Macon College in Virginia.

The success of “A Christmas Carol” helped shift Yuletide ghost stories from the family parlor into the mainstream, and its publication prompted a flurry of Christmas novellas and short stories for a thirsty audience.

“It just reminded people that, hey, ghosts really sell at Christmas time,” said Tara Moore, a professor at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

(Though Americans share the fondness for “A Christmas Carol,” historians say Christmas ghost stories did not quite cross over with the same fervor, perhaps because such spookiness became more associated with Halloween.)

Since 2005, the BBC has produced adaptations of ghost stories at Christmas; this year’s Christmas Eve entry stars Kit Harington of “Game of Thrones” in an adaptation of a tale by Arthur Conan Doyle. Theater companies have adapted ghost stories for stages like Shakespeare’s Globe.

But do people still want Christmas to be scary?

George Hoyle, who runs the South East London Folklore Society, thinks they do. Hoyle discussed the history of the tradition before reading a famous tale to audiences at a local cafe this month.

“It is a scary place, but it’s safe at the same time, because we are all together,” he said of contrasting the coziness of a warm cafe with the spooky tales. Mulled wine and minced pies were served.

Several of Maguire’s ghost story nights sold out, and the company also hosted a competition for locals to submit their own ghost tales to be performed.

“It’s mankind’s oldest form of entertainment,” he said. “It’s cold, it’s dark, and people want to have that kind of fear factor.”

Ghost stories tend to remind people to reflect on their morals, values and how precious time is spent, something that still resonates in today’s working world, Cadwallader said. “We are as busy as the Victorians were – and we still find it comforting to step out of time for a little bit.”

So, gather some friends. Draw the blinds. Read some tried and tested chillers, like Gaskell’s “The Old Nurse’s Story,” or James’ “The Mezzotint.” Listen – what was that sound? A whisper? A guilty conscience? Or the sound of Christmas on its way?

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.