What Biden can learn from the Revolution

Few presidents have entered the White House with as much foreign policy experience as Joe Biden – 30 years on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, four as its chairman, eight as vice president during a time of war and global financial collapse. Yet he is already struggling to manage one of the central tensions of American statecraft – between the need to make cold-blooded decisions to protect US interests and the belief, strongly held in many quarters, that the United States also should defend and advance democracy and human rights beyond its borders.

In a February 5 speech before State Department employees, Biden called for a diplomacy “rooted in America’s most cherished democratic values: defending freedom, championing opportunity, upholding universal rights, respecting the rule of law, and treating every person with dignity.” A few weeks later, his administration released a report confirming that Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman approved the operation that led to the murder of the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. The administration also imposed sanctions on 76 of the individuals involved and froze military sales to the kingdom. But Biden chose not to sanction MBS himself, out of fear of losing Saudi cooperation in countering terrorism and Iran. As a result, he was widely castigated in Congress and the press for being a hypocrite on human rights.

Donald Trump was the rare president who escaped this “idealism”-versus-“realism” quandary in international affairs, thanks largely to the incoherence of his own foreign policy views and the fact that he sincerely didn’t give a shit about democracy, human rights, and the rule of law – and convinced his followers not to care, either. But he was also aided by the blunders of his predecessors that gave democracy promotion a bad name. George W. Bush launched a catastrophic ground war in Iraq with hyperbolic statements about “ending tyranny in the world.” Barack Obama gave eloquent rhetorical support to Arab Spring uprisings but chose not to commit American might to defend them – except in the case of Libya, which didn’t turn out too well. For examples of presidents more successfully balancing morality and realpolitik one has to go back to Bill Clinton’s ending of the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo or Ronald Reagan’s brinkmanship with the Soviet Union.

But to fully appreciate how deeply rooted this tension in US foreign policy is, it helps to look back even further, to when it first manifested itself two centuries ago during the presidency of James Monroe. Like Biden, Monroe governed during a time of rising autocracy. The European powers had recently come together at the Congress of Vienna to re-establish the monarchies Napoleon had overthrown. Their militaries were crushing democratic uprisings in Spain, Portugal, and Italy – and threatening to do so to independence movements in Latin America.

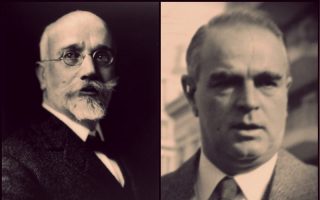

It was in this environment that Monroe articulated a foreign policy doctrine, mostly written by his secretary of state and White House successor John Quincy Adams, that today bears his name. The Monroe Doctrine declared that the United States would consider any attempt by a European state to oppress or control any country in the Western Hemisphere a hostile act. It was intended as a warning to the colonial powers not to restrict the potential spread of democracy in Central and South America nor press any claims on North American territory, thereby clearing the way for US westward expansion. The doctrine also stated that, in return, the United States would not involve itself in the affairs of Europe – a vow meant to protect the ability of American merchants to trade freely on an equal footing without being caught up in Europe’s endless commercial intrigues.

But just as Monroe and Adams were formulating their new policy, an unexpected event occurred that complicated their plans. On March 25, 1821, Christians in southern Greece launched an insurrection against their Ottoman Turkish overlords and declared the creation of an independent democratic Greek state. News of this event captivated the Western public. Pressure quickly grew in the press and Congress for the United States to recognize the new Greek government and support its war of independence.

The public’s support for the Greek cause was partly out of religious prejudice. The Turks were Muslims, and their oppression of the Greeks, including massacres of the innocent, were widely reported. (Greek slaughter of innocent Turks, less so.) But it was also because the educated classes in the West had become obsessed with the glories of Classical Greece as the result of the greater availability of ancient Greek texts in translation. The idea that the modern Greeks might throw off tyranny and rebuild the virtuous self-governing civilization of their ancestors fired the imaginations of Westerners with republican sympathies – most notably Lord Byron, the English Romantic whose wildly popular poetry gave voice to the idea. It acquired a name: philhellenism – a Greek word meaning “love of Greece.”

Philhellenism was especially strong in the United States. As citizens of the world’s lone republic, Americans had come to see themselves as the inheritors of Greek democracy. The spread of Greek revival architecture and the naming of American towns after ancient Greek ones – Syracuse, New York; Athens, Georgia – give you a sense of how culturally potent this sentiment was at the time. Monroe himself had some sympathy for the idea of formally supporting the Greek revolution, a position he knew was popular with American voters. So too did his secretary of war, John C. Calhoun, and Speaker of the House Henry Clay, both of whom were eyeing runs for the presidency in the next election.

John Quincy Adams, however, who was also contemplating a White House bid, believed otherwise. Not only would formally siding with the Greeks contradict the promise of neutrality that was central to Adams’ strategy toward Europe, it would also undermine his efforts to secure a trade treaty with the Ottoman Empire. “Their enthusiasm for the Greeks is all sentiment,” Adams privately wrote of his philhellenic rivals. The sentiment, however, was shared by many of the country’s most revered elder statesmen. Former President James Madison proposed that Monroe enlist England in a joint statement in support of the Greek war.

Thomas Jefferson sent the leading Greek revolutionary thinker Adamantios Koraes, whom he had gotten to know in France when he was the US ambassador, advice on how to structure the new Greek government on American principles – though cautioning his old friend against expecting US support. Even John Quincy Adams’ own father, former President John Adams, confided to Jefferson that “my old imagination is kindling into a kind of missionary enthusiasm for the Greek cause.” But in the end, Monroe sided with the younger Adams that neutrality was the safer course. When Monroe finally delivered his doctrine publicly in the 1823 State of the Union address, he proclaimed his faith that the Greeks would free themselves but did not endorse formally recognizing the new Greek government.

Philhellenes in Congress led by Henry Clay and Daniel Webster countered with a proposal expressing disapproval of the president’s neutral position while encouraging him to send an agent to Greece to collect information. In the days-long debate that followed, Webster made what might be the earliest – and is certainly one of the most masterful – congressional speeches ever delivered on the need for the United States to stand for democracy and human rights in its foreign policy, asking, “Is it not a duty imposed on us, to give our weight to the side of liberty and justice?” He also argued that as a practical matter, the views of average citizens needed to be taken into account in charting America’s foreign policy, as “the public opinion of the civilized world is rapidly gaining an ascendency over brute force.” In the end, however, Congress adjourned without voting on the proposal.

But Webster turned out to be at least partially right about the power of public opinion. After the federal government decided not to get involved in the Greek War of Independence, the American people chose to do so directly. In cities and towns all over the country, citizens banded together to raise money for the Greek war effort, from fancy dress balls for the elite in Boston to collection plates at Methodist churches in the Midwest. Soon, ships laden with weapons and other supplies were leaving New York and Boston on their way to Piraeus, Nafplio and other Greek ports. Some assistance was even more direct. Over the 10-year course of the war, a dozen Americans went to Greece to fight as volunteers.

American support, though helpful, was hardly decisive to the war’s outcome. The Greek people, despite their often fumbling leadership, won it with their own blood – though only after the European powers reluctantly got involved and, somewhat by accident, sank the Turkish Navy at Navarino. The sizable quantities of humanitarian aid sent by average Americans, however, did save countless Greek lives. The US effort is currently the subject of considerable media coverage in Greece as that country celebrates the bicentennial of the war.

While most Americans have no memory of US involvement, the experience arguably had a more lasting impact in America than in Greece. As the historian Maureen Connors Santelli details in her new book, “The Greek Fire: American-Ottoman Relations and Democratic Fervor in the Age of Revolutions,” the charitable drives for Greece provided American women their first-ever opportunity to be publicly involved in foreign affairs and thus fed a nascent women’s rights movement. Indeed, some early feminist leaders were prominent philhellenes, including the educator Emma Willard, who sent teachers to Greece to establish schools there after the war.

Santelli further documents how widespread public empathy for the Greeks living under Turkish oppression also led, over the course of the war, to more open questioning of American enslavement of African Americans. Indeed, the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison originally contemplated going to fight in Greece before deciding to do battle against slavery in America as a journalist and newspaper publisher, writing at one point that rebellious southern slaves “deserve no more censure than the Greeks.”

Some of the Americans who did actually journey abroad to fight returned home to become noted anti-slavery crusaders. The stirring of national conscience that resulted from debate over the war was so profound that the abolitionist Franklin Benjamin Sanborn would later say that the eventual ending of slavery in the US had “begun in Greece.”

One could make the case, then, that Monroe and Adams managed America’s response to the Greek revolution masterfully. By insisting that the US government remain neutral but tolerating and even enabling private involvement by the American public (US naval forces actively protected the private cargo ships ferrying supplies to Greece), they found a clever way to balance the tension between realpolitik and idealism. It allowed them to minimize the risk of war while continuing to pursue a trade deal with the Turks.

It’s also arguable, however, that Monroe and Adams were too clever by half. The trade negotiations between Washington and Constantinople went nowhere until after the war, in part precisely because the Ottoman officials couldn’t make sense of the mixed public-private messages they were getting from the Americans regarding the Greek situation. It’s entirely understandable that the Monroe administration feared provoking the animus of the Great Powers, but in retrospect it’s clear that those powers were in no position to reassert their colonial authority or stop America’s westward expansion.

By playing it safe, the administration missed an opportunity – one philhellenes like Daniel Webster advised they seize – to make an official statement to the world that the United States stood against the rising tyranny of the time. Such a statement might have proved helpful to the many independence movements in Europe and elsewhere that were to come.

The world is obviously vastly different than it was two centuries ago. America was then a young and rising free nation with growing prosperity and equality (for white men). Europe was in the grip of reactionary tyranny, from which the United States wisely sought to isolate itself. Today, both the US and the nations of Europe are democracies enmeshed with each other in alliances like NATO that have kept the peace and protected their freedoms for nearly three-quarters of a century. But both are also suffering from growing inequality and downward mobility.

Still, the parallels between 1821 and 2021 are worth paying attention to. Now as then, authoritarianism is on the march. According to the latest assessment from Freedom House, democracy has been in worldwide decline for 15 straight years, including here in the United States over the past four, thanks in no small part to authoritarian meddling by Russia and China.

The need to balance the demands of principle and practicality in foreign affairs is as great now as it was 200 years ago, if not greater. Biden will have to find that balance as he navigates a host of individual foreign policy challenges, such as the military coup in Myanmar, China’s continuing genocide against the Uyghurs, and the increasing authoritarianism and provocations of Turkey’s neo-Ottoman leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

What Biden needs is a doctrine of his own – a comprehensive and workable strategy that can both advance our economic and security interests and defend democracy against resurgent authoritarianism. In this issue, Wesley Clark, the former supreme allied commander of NATO who led the successful military intervention in Kosovo, proposes such a strategy.

It would involve a new binding agreement between the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom on policies such as trade, antitrust, and technology transfer to counter the predations of tyrannical states like China while reversing the economic gutting of the middle and working classes that breeds right-wing populism here and around the world. Trumpian fears of China, Clark argues, might motivate some GOP support for such an agreement. If not, it could be negotiated as a trade deal, which Senate Democrats could pass on their own.

How much enthusiasm there would be among Democrats for such an agreement is another matter. Liberal-minded citizens have historically provided much of the energy behind demands for a more democracy- and human rights-based foreign policy. Today’s left, however, seems relatively quiescent on that front. This is partly out of disenchantment, especially among young people, with almost any application of US global power. It is also based on the feeling that we have no business lecturing anyone overseas about democracy and human rights when we still have immense structural racism and sexism here at home.

On that point, the story of US involvement with the Greek War of Independence is especially instructive. In ways no one could have foreseen, America’s engagement in that fight accelerated necessary confrontations with our own society’s wrongs. That same dynamic played out in later conflicts, too. The need for mass mobilization in World War II compelled the US government to integrate white ethnic communities into the mainstream culture. The need to counter Soviet propaganda during the Cold War opened the way to civil rights advances for Black people. If progressives want to dismantle racist and sexist systems in America, they should set their sights higher by also demanding that their government advance policies that protect and defend democracy and equal rights around the world.

Paul Glastris is the editor in chief of the Washington Monthly. He is writing a book on America’s involvement in the Greek War of Independence.