Confusing love of art with love of owning art

The agreements signed over seized Cycladic antiquities in the US cannot serve as a repatriation model for the Parthenon Sculptures.

For nearly a century, the marble figures that were produced in the Early Bronze Age (ca 3300-2300 BCE) on the Greek islands of the Cyclades have fascinated archaeologists, art historians and collectors; they also had a strong impact on Early Modernism. They owe their charm to the minimalist aesthetics of their makers and the ability of those artists to bring to life a complex world of activities, beliefs and emotions. More than half of the Cycladic idols known today were found during illicit excavations, mainly in the 1960s and 1970s. In order to satisfy the insatiable appetite of collectors, the looters of Cycladic cemeteries have forever destroyed the contexts that modern scholars need in order to date and interpret these artifacts. When the supply of looters could not satisfy the demand of collectors, skilled forgers stepped in. Two of them were inhabitants of Ios: Angelos Batsalis (1885-1953) was active in the second decade of the 20th century. The English painter John Craxton met another one in 1947: the shepherd Angelos Koutsoupis, to whom many archaeologists attribute the famous harpist in the Metropolitan Museum. Another forger was interviewed by a team of archaeologists; he revealed his method and identified objects in private collections as his work.

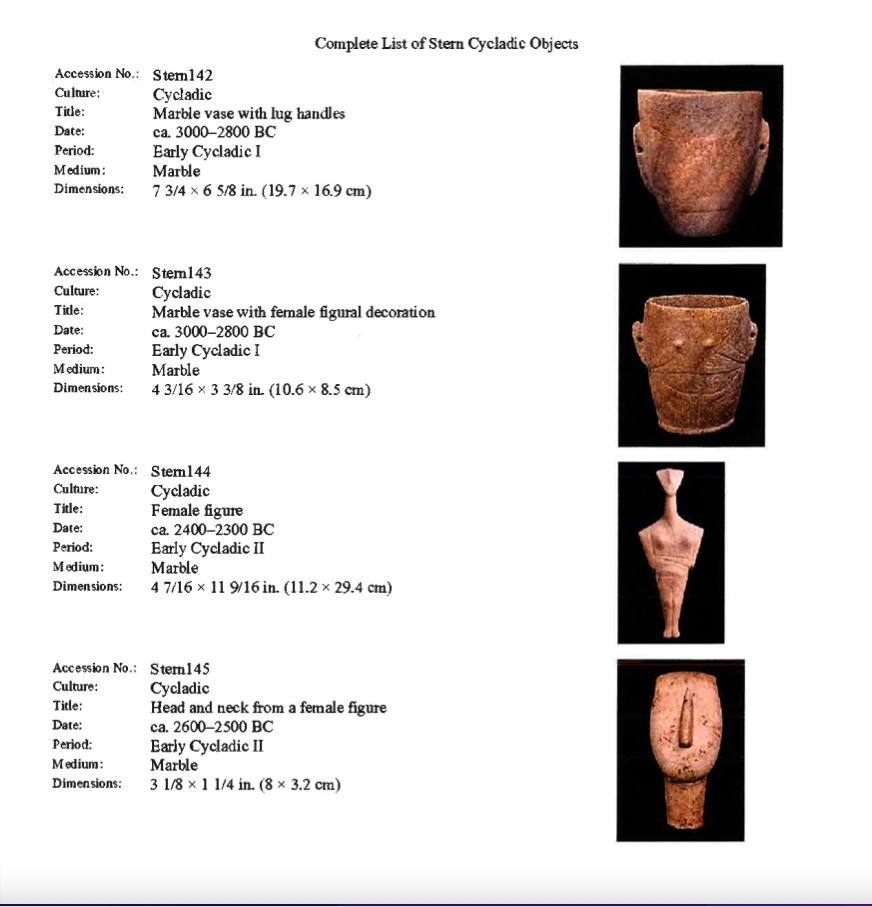

Cycladic works were among the looted antiquities that the billionaire Michael Steinhardt had to surrender in December 2021, in order to avoid charges. In the words of former Manhattan district attorney Cyrus Vance Jr, “for decades, Michael Steinhardt displayed a rapacious appetite for plundered artifacts without concern for the legality of his actions, the legitimacy of the pieces he bought and sold, or the grievous cultural damage he wrought across the globe.” Only six months later, on July 21, 2022, another collector of antiquities, Leonard N. Stern, signed an agreement with the not-for-profit organization Hellenic Ancient Culture Institute (HACI), contributing “his rights and interests in the collection including his right of possession” to HACI, under the condition that HACI enters into an agreement with the Metropolitan Museum for the display of the collection. HACI was founded in order to carry out “the charitable and educational purposes and activities of the Museum of Cycladic Art of the Nicholas P. Goulandris Foundation in Athens. On the same day, both the Exhibition Agreement between HACI and the Metropolitan Museum and an agreement between HACI, the Met, the Cycladic Museum, and the Greek Ministry of Culture were signed. Their result is the exhibition that was opened at the Met on January 24. The curator Sean Hemingway praised these agreements as “an exciting new model for repatriation.” In conversation with David Nirenberg at the Institute for Advanced Study on March 23, 2023, Daniel Weiss, president and CEO of the Met, called these agreements a model to be followed for the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum. Really? Let us examine their content.

More than half of the Cycladic idols known today were found during illicit excavations, mainly in the 1960s and 1970s

In accordance with the agreements, only 15 out of the 161 objects of the collection were displayed at the Cycladic Museum for one year (November 1, 2022 through October 31, 2023); they are now, together with the rest of the collection, in the Met, where they will stay for 10 years. Then, for a period of 15 years starting in 2034, parts of the collection will be transferred to Greece “to be displayed at the Museum [of Cycladic Art] and/or any such other museum in Greece.” There will be three deliveries of 15 objects each, in 2034, 2039 and 2044. Each time, the 15 works “removed from the Met will be replaced under the responsibility of HACI, with an equal number of pieces of Cycladic art from Greece of equal significance and beauty as the works of the collection.” They will be displayed at the Met until December 31, 2048. The agreement with the Greek ministry states (Article 6D): “The Met will be obliged to display in the same installation where the collection is displayed, antiquities of the Cycladic civilization from the collections of the Cycladic Museum and/or other museums of Greece that the Greek state will be obliged to send to the Met by way of loan. These antiquities will be selected by the ministry in consultation with the Cycladic Museum, considering inter alia and if possible, the types of antiquities that are not already represented in the collection, will be of equivalent value and significance as the antiquities sent for display at the Cycladic Museum as per previous par. 5(C), will be approved by the Cycladic Museum and the Met, and will be sent to the Met, on loan.”

This “tit for tat” agreement begs three questions. First, how does one determine “equal significance and beauty” and, more importantly, “equivalent value and significance”? Does one ask an antiquities dealer in Basel what the current price of a Cycladic figurine is per square centimeter? Second, why should public museums of Greece provide exhibits in exchange for works that will not be displayed in these public museums but in the private Museum of Cycladic Art? And thirdly, why is it not guaranteed that the Cycladic works will be really repatriated, that is, returned to the Cyclades? The director of the Department of Antiquities of the Cyclades, Dr Demetrios Athanasoulis, stated that “it is the declared policy of the Ministry of Culture that products of illicit trade of antiquities belonging to the Cycladic culture and lacking a known provenance, either confiscated or returned, are to come to Naxos; it is self-evident that this is the final destination of Cycladic antiquities such as the Stern collection.” However, the Ministry of Culture failed to commit itself to this in these agreements.

What happens after 2048? The Exhibition Agreement (Article 7E) and the agreement with the Greek Ministry (Article 6F) provide for two options: The Greek state will either “agree with the Met to loan the whole collection for a period no longer than 25 years,” until 2073, or the remaining objects will be shipped to Greece in exchange for “122 pieces of Cycladic art of equal significance and beauty” to be given to the Met for 25 years. The exhibition in Athens was given the title “Homecoming: Cycladic Treasures on their Return Journey.” Odysseus’ homecoming to Ithaca lasted for 10 years. The Stern Collection will need between 25 years and half a century to see the light of the Cyclades.

More questions arise when we read the agreement between HACI, the Met, Cycladic Museum, and the Greek Ministry of Culture. The ministry acknowledges that the purposes of HACI, located in the tax paradise of Delaware, include “obtaining, by way of donations, loans or bequests, ownership and/or possession of works of art, objects and monuments from Greece dating back to the period from prehistoric times to the Middle Ages and seeing to their safekeeping, study, and conservation of antiquities, being entitled to transfer them to the Cycladic Museum or other museums in Greece, under decisions adopted by its Board of Directors in accordance with the laws of the Hellenic Republic on cultural heritage.”

The deal

What are the consequences of this permission given by the ministry to HACI? Hypothetically, can an owner of antiquities acquired illicitly donate their collection to a not-for-profit organization and receive a tax deduction for their donation, while the looted antiquities are “washed clean”? Not being a legal scholar, I cannot provide the answer to this question, which is anything but rhetorical. And why is HACI only “entitled to” and not obliged to repatriate these antiquities?

The Greek state approved by law “HACI’s right to possession of the collection” (Article 3C), while “Greek Patrimony Law provides that the Greek state is the sole owner of the collection” (Article 5). One is in possession of an object whose sole owner is somebody else either through theft or by means of a loan. And, indeed, the wall adjacent to the collection informs the visitors that the objects are a “Loan of Cycladic Art to the Met” (Article 11).

But these objects became a loan ex post, by virtue of these agreements. What were they before? In an article in The Art Newspaper of January 25, 2024, Gabriella Angeleti states that at the opening of the Met display the Greek minister of culture emphasized “that there is no evidence that the artifacts were illegally excavated or acquired.” The minister said something completely different:

“None of the 161 antiquities has ever been recorded as stolen and there is also no evidence or any indicative information about when and how they were discovered and exported from Greek territory or about their route and fate until they reached New York.” It is in the nature of looted antiquities that we do not have information about their provenance and their route from the looter to an antiquities dealer and, supplied with documentation of previous ownership, to a collector. Legal excavations in Greece are conducted with permission of the Archaeological Service and their finds do not end up in private collections.

It is in the nature of looted antiquities that we do not have information about their provenance or their route to an antiquities dealer

As already mentioned, these agreements have been called a model to be followed for the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum. But while the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum are parts of a single work of art, fragmented and mutilated by Elgin’s agents in 1801, the Stern Collection is a heterogeneous assemblage of 161 objects of different provenances and times. How can the Stern Collection serve as a repatriation model? Should a group of horsemen from the Parthenon frieze in the British Museum be displayed for 10 years in the Acropolis Museum in exchange for the display of the Charioteer of Delphi and the Jockey of Artemision in the British Museum, together with the rest of the Parthenon Sculptures? This is neither repatriation nor reunification of a fragmented work of art but the perpetuation of the destruction of a monument.

Collectors of Cycladic antiquities claim that they collect them because of their love for Cycladic culture. They confuse the love of art with the love of owning art. If they really love the Cycladic culture, they should fund systematic excavations, instead of contributing to the destruction of contexts.

Angelos Chaniotis is professor of ancient history and classics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.