Taking a step back for a longer perspective

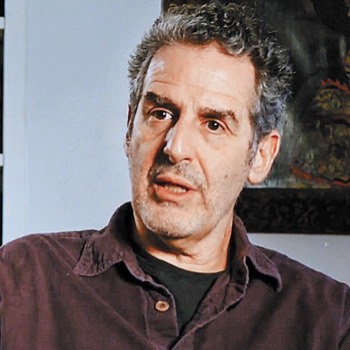

Mark Mazower has systematically studied modern Greek history, hence a discussion with him amid celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the Greek Revolution promises to be very interesting on many levels. Besides, as a member of the Greece 2021 committee, the British historian has personally contributed to preparations to mark the bicentenary of the 19th century War of Independence against Ottoman Turkey.

Mazower, who is Ira D. Wallach Professor of History at Columbia University in New York City, recently visited Greece to address an event organized by the Justice Ministry. Speakers included President Katerina Sakellaropoulou and Justice Minister Kostas Tsiaras. Mazower’s own talk focused on the types of justice during the Greek War of Independence.

However, in this interview, he touches upon many more aspects of the Greek struggle while exploring its modern perception: the endurance of Greek society in 1821, our devotion to the heroes of the day and the opportunities offered by a national anniversary are some of these.

Which questions should we ask when evaluating a national anniversary like the bicentennial of the Greek Revolution?

Which questions should we ask when evaluating a national anniversary like the bicentennial of the Greek Revolution?

A national anniversary is not a fact of nature but the product of a political decision, sometimes collective, sometimes less so. With time, such celebrations can become established while others may disappear or be abolished. Who today celebrates the date on which King Otto set foot on Greek soil? It has been long forgotten. Yet in fact it preceded the establishment of March 25 as a national holiday. The bicentennial year of the outbreak of the Greek Revolution offers a rare opportunity to step back from the very short-term preoccupations that normally beset us and think in a much longer perspective. In some ways this may be especially valuable today. The way we receive information and news today is ever more breathless; it becomes harder and harder to find a moment of reflection and contemplation on what events mean because everyone is supposed to have an instant reaction. Moreover, we are gradually losing the habit of, as the historian Carl Schorske once put it, “thinking with history.” Thus the bicentennial is a moment to try to come to terms with the very radical break with the past that was represented by the establishment of an independent Greece, to ask what independence really meant and to chart the distance the country has come since then. By the same token, it is a chance to think a little about the future.

We tend to think in such moments along two axes: a) was it a success or a failure? b) should we be pessimistic or optimistic for the future? I think that like any relationship, our relationship with history is too complicated and too multifaceted to be embraced by such dichotomies. Already we have benefited from a number of very important exhibitions and publications that will stand as lasting testimonies to the value of this occasion.

In his work of the same name, Eric Hobsbawm argued that national rituals and celebrations could be largely described by what he called “the invention of tradition.” Is it something unavoidable, given the after all unifying impact that the concept of nation has on the historical past? Did you have to engage with similar issues as a member of the Greece 2021 committee?

Hobsbawm, and others, have helped us see how much we have inherited from a 19th century obsession with history and from its need to create traditions where they could not be found, or to make whole myths out of scraps and pieces. That does not mean that all traditions are invented or that the sense of the past is a modern invention. To put it abstractly, it does mean we have to be careful not to mistake essence for process: We have inherited conceptions of Hellenism and Greece from the past: but different versions of them have emerged at different points in time.

Υou are writing a new book on the Greek Revolution. Have you traced any new directions in the 1821 historiography that is being published in large amounts these days and, if so, under what “school” (if any) would you categorize your upcoming work? What is the main argument of your new book?

The first thing to say is that scholarly history flourishes in Greece as in few if any other countries of comparable size. Some classic works were written on the Greek Revolution in the 19th century; but no serious scholar today can write about the subject without taking into account the works that have come out in Greece in the past 20 to 30 years: We know far more than we once did about the economics of the revolution, about the all-encompassing Ottoman dimension, about the war at sea, about the Etaireia and those who joined it and what they thought. So my book will be in part a work of synthesis and a kind of homage to the work of my Greek colleagues.

At the same time, it will – I hope – provide a fresh and interesting interpretation. The story of 1821 is in many ways a very complicated story. I think that is one reason why we tend to fixate on the heroes – because they make it all much more simple to understand. In fact, it took place across many different regions, in fits and starts. There was a failed beginning, for one thing, under Alexandros Ypsilantis. Also, the Greeks were facing defeat in the face by the summer of 1827 and would not have won their freedom without allied support. Yet what does this also mean? That for six years the Greeks – at least of the Morea, the islands and some parts of Rumeli – had already held out for far longer than anyone in Europe had imagined they could back in 1821. That endurance, that stamina – to use the phrase now much in vogue – that resilience of Greek society strikes me as the key element and the one that fascinated me the most.

You recently spoke about forms of justice during the Greek Revolution. What’s the most important thing that you would say about that topic to a citizen that is sometimes suspicious about their country’s judicial institutions? Can we trace the so-called misfortunes of modern Greece to the beginnings of the Greek state or is that not the case at all?

Institutions are unfashionable – state institutions above all: Few people fall in love with institutions. What I think the history of 1821 shows us is what a society looks like when it is between institutions – when old institutions have ceased to function and new ones have not yet come into being. The Ottoman state had collapsed; the new state of the Bavarian monarchy had not yet been imagined. Was that vacuum a preferable state of affairs? Ask the peasants of central Rumeli, who were at the mercy of whichever “oplarchigos” and whichever band of armed men held power at the moment. The work of constructing judicial institutions was hard and after 1821 it lagged behind the more glamorous and public business of establishing the other two branches of government. Between the texts of revolutionary constitutions and the realities of what justice meant there was, in the 1820s, a vast gap and it is this that interests me as a historian.

In 2022 Greece will commemorate the unfortunate end of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22. What kind of reflection would you, as a historian, like to see then, given that the commemorated event will be one of loss, not victory?

When there are too many of them, commemorations risk losing their impact. But the “katastrofi” was obviously a fundamental moment in the emergence of the modern Greek state. One might almost say it was only then, a century on, that the revolution of 1821 really ended. The human suffering was immense and no less important the challenge the refugee crisis posed for the state. Society in northern Greece in particular would have developed in very different ways without this enormous movement of populations. And two other longer-term consequences of these events strike me. One, that it transformed the relationship between Greeks and Turks – simultaneously breaking old ties, as Muslims departed from Greece and Orthodox Christians from Anatolia and the Black Sea; and intensifying them, as Greece received a new influx of populations who had lived for centuries with Muslim neighbors and who often spoke Turkish as well as if not better than Greek. The second is that the “katastrofi” heralded a new relationship between the nation and territory. The old ideal had been to grab as much territory as possible, as if land itself was the prize; today we live in a very different world, one that perhaps began in that moment.

From David Harvey to Craig Calhoun, the opinions about the role of nation-states in the 21st century vary a lot. According to you, which is the role, the meaning of those “imagined communities” (and their celebrations) in a globalized world where people, money, products and information are constantly flowing across borders?

I think what is striking is how powerful national-states remain today. They embody senses of political community that are not easily dispelled, perhaps because they have been associated with ever-widening political and economic social participation. Globalization presents a huge challenge to them. Yet 19th century political thinkers understood something that often escapes us today, namely that national politics and international cooperation are not opposites but complementary. Small countries, at the mercy of larger ones, know this by experience. But in the face of global warming, even large countries are small ones now.

What about the pandemic? Should we expect that it will strengthen cosmopolitan views (based on the realization of our species’ vulnerability) or that it will make us more introvert, nationally speaking? Can public health (as a policy but also as an objective, as a collective goal or even a concept) play a role toward more inclusive societies?

I lived through the pandemic in Manhattan and saw moments of enormous social solidarity at the same time as people tried to isolate themselves and ignore those around them. With time, the latter realized this was not possible. Thus what I saw was the pandemic reinforcing notions of the public good and social solidarity that had been on the retreat for many years. I hope this will continue. But when crises end, these are often the lessons that are most quickly forgotten.