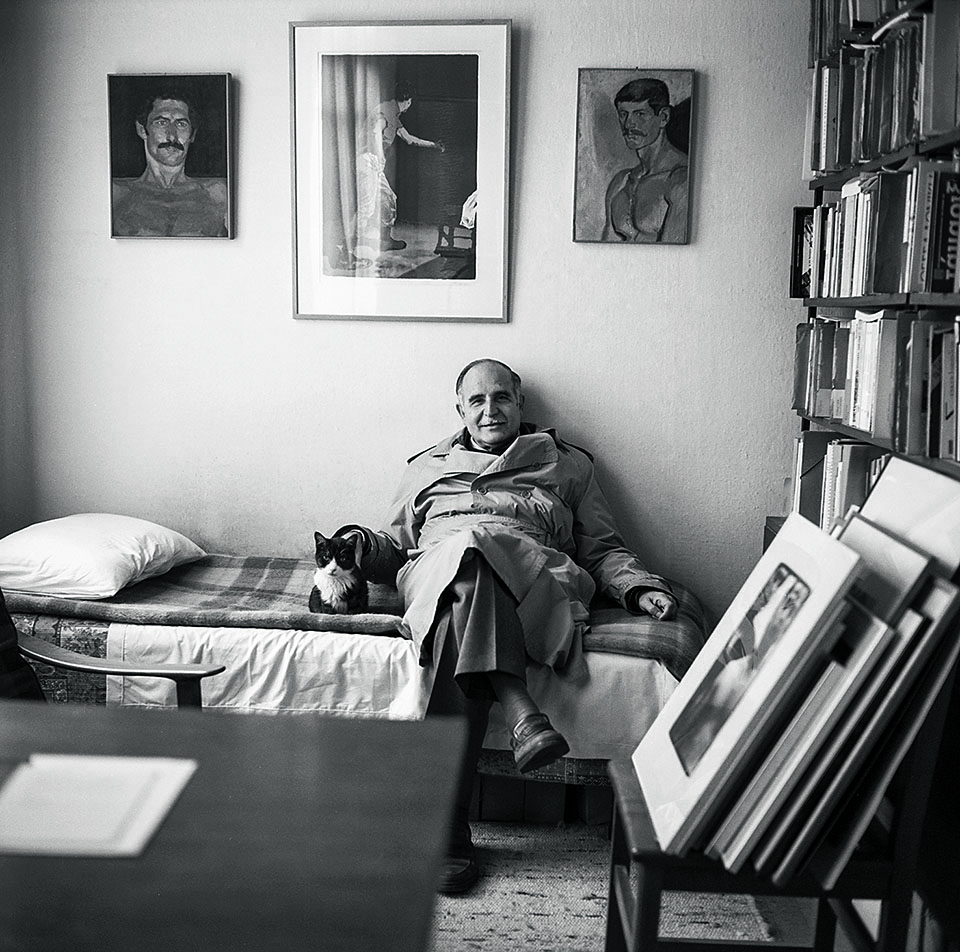

Portrait of a photographer

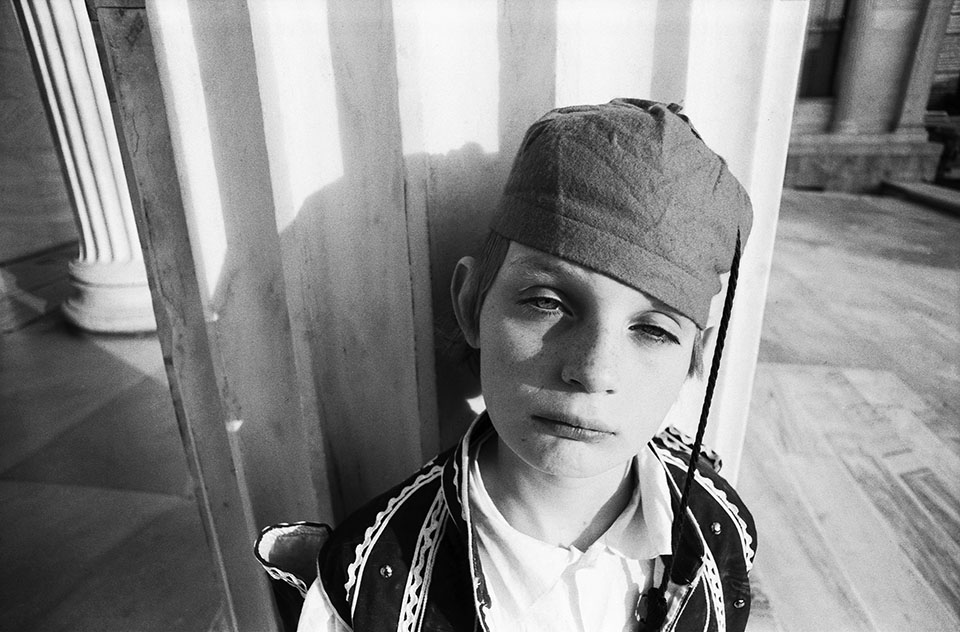

Idiosyncratic and influential lensman discusses the motivation behind his new book, his process and contemporary image culture

As radical and influential a man as he is a photographer, Spyros Staveris is also surprisingly modest and softly spoken.

We met on the occasion of the release of his book “There Is Nothing Behind a Photo,” published by Polis during the lockdown. It consists mainly of work from the second half of the 1980s, after his return from Paris and before he became involved with Greek and foreign magazines. It was a transitional phase for Staveris, who was still exploring his identity and leanings.

The images in this collection are accompanied by notes he made at the time, much like a journal which, he says, paints a “more authentic” portrait of the photographer himself.

Mapping a discursive course between the lumpen fringes and the lifestyle of Athenian socialites, Staveris went on to earn a reputation for his portraits of abnormals (in Foucault-speak) but also of celebrities.

Drawing on a surfeit of experiences packed into some three decades, Staveris spoke of the inspiration and motivation behind his new book, his process and today’s image culture.

You have not been stationary during the pandemic. The new book is proof of that.

Artistically, I put down my arms some time ago in photography. What I mean is that I did not feel that I had anything new to say and I did not want to start repeating myself. It would be really hard for me right now if you said, “Go take a portrait” – a real chore. At some point I just started using my phone to photograph my wanderings, just like everyone else does.

One might assume that a mature and established photographer like yourself would look down on that trend. Do you do it because everyone else does it, to see what it’s like? Or do you find it somewhat liberating?

That’s it exactly. I wanted to try a new medium that I saw gaining a place in modern reporting. I also wanted to feel the freedom the phone gives you – to shoot whatever, whenever it draws your attention.

Are you put off at allby the sheer volume of imagery, the direct sharing on such a massive scale, the narcissism of selfies? Many claim that photography is being debased by the process.

I don’t see it that way. That it has become so democratized is great. People are learning to train their eye. I also see something very tender in it, especially with youngsters and their selfies. I don’t have an elitist attitude to the issue.

Can you explain the book’s title? It’s poignant but also contradictory given that the images are accompanied by notes and text.

The entire book came out unwittingly; it was unexpected and unintentional. And the title was kind of a separate thing. I felt it suited the book because it puts you in the paradoxical position of anticipating what it could all mean, through the stories in the book.

Was there a purpose to all this?

What I wanted and what I ultimately accomplished was a portrait of the photographer through the photographs and their accompanying texts. Readers see someone they didn’t know. The fact is that many people, at first especially, thought I was a complete freak; others thought I was some brilliant intellectual – which I am not by any means. They had this erroneous image of me. And I think that a more authentic portrait of me emerges from this book.

What criteria did you use to develop the book?

I noticed at some point that I had writings that suited particular photographs, so I started putting it all together and forming the bones of a potential book. The succession is random, but I wanted it to have a sense of continuity, variety, perhaps even rhythm. And they are all black and white because I am referring to a time when I shot in black and white, before I got into color, which the magazines demanded.

The writings are based on notes you took when you got back home every day, right?

Exactly. It was a time when I felt incredibly free, because I was free of cares, and it was my habit at night to keep something like a journal describing the things I’d done and people I’d seen. It was something that lasted just for that decade, roughly. Because later, after I become involved with the magazines, photography took on a different intensity that did not allow me to sit down at night to write. It’s a real shame, because I met a lot of interesting people later and it would have been very useful to have notes on these encounters, which I now hardly remember.

Could these photographs be shown on their own, without words?

I think many of the photographs in this book could stand alone, or even beside others, because a photograph takes strength from the one beside it too.

You studied in Paris, where you also watched a lot of films. Did that influence your work?

Definitely, though I didn’t realize it of course. Back then I wanted to do something with cinema, but I never found the channel, the way, so it just stayed that way: a desire. I watched Walter Ruttmann’s “Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis” one day and I felt that this is exactly what I had been trying to do all those years, even though I did not have it as a specific reference in mind. The portrait of a city, basically. There was a spell when I was not considering becoming a photographer at all; I just took photographs for the pleasure of it. These here are photographs from a transitional time when I was doing different odd jobs and had just emerged from a period of intense political activism in the wake of May 1968. Myself and many of my contemporaries found ourselves a bit lost at the time. Even though there were opportunities in Greece in the 1980s to get mixed up in things and stay politically engaged, the overall framework was somewhat disheartening. And it was in this condition that I discovered the city, discovered Athens.

Later, as a photographer proper, you moved in the fringes, but also at celebrity parties. Where were you most in your element?

I felt comfortable everywhere. Whether you take me to a club or a hotel room with a transgender woman and her boyfriend, or the social scene I did then. If you are curious about things, about social phenomena, about the different categories of people, I think this curiosity makes you see everything, not from a distance, necessarily – because you can have feelings about what you’re looking at – but it allows you to move around comfortably everywhere. If there is anything that comes across, I think it’s a greater tenderness for the marginalized than the socialites.

Celebration of vanity

You refer to curiosity as a driving force. Can the process of photography change the photographer? Can it give them greater courage?

It’s the camera that gives you courage at first. But I became a different person by working with and meeting people who basically helped me find myself. I’m talking about the 2001 period with Stathis Tsagarousianos, which was pivotal. Until then, I had been doing classic, Magnum-style photo-reporting. But something different started coming through at some point, something I was only just discovering myself. I started photographing differently: freer, more dynamically, perhaps in a funnier way.

When you started doing celebrity and lifestyle photography it was something unfamiliar. How did you sell it?

I didn’t need to sell anything. Tsagarousianos was running Symbol at the time and because there was an explosion of events, the stock market and all the rest of it, he suggested that we also do something with society pages, but in a different way. Walking past a photography shop, I spied a 6×6 [medium-format camera] and thought about how it would allow me to change direction. It was cheap, Japanese, and I used it to start shooting for the society pages. And it did take me somewhere else. Even the medium can make you change direction. And, of course, we didn’t take the photographs other society photographers were doing, your typical portraits and the gowns.

Was there something about the predominant forms at the time that you wanted to challenge?

No, I just wanted a more journalistic style. And funnier, in a way. Isn’t it all really just a big celebration of vanity? So, that’s what I had to show it as.

How do you capture such an atmosphere? Do you do research? Location scouting? Do you have to experience it?

There aren’t many luxuries in portraits, in Greece especially. You’re sent somewhere and you have three minutes to get the shot. You have to be on your toes. You turn up at a house and have to scan all the corners immediately, see what possibilities it offers, put the person where you will get the most information. I always tried to do this with portraits and this is something the 6×6 allowed. I didn’t take close-ups; it was always a face in its proper environment. As far as research is concerned, all the reading accumulates in you without you knowing it, together with all the things you see.

Describing your encounter with Dinos Christianopoulos in the book, you say that photography is like choreography. Would you care to explain?

You have to move a lot, be agile. You can’t set up your tripod in one spot and the person across from it and say, “That’s it.” You need to try different things and make the person move as well. You’re a bit like a choreographer.

Ultimately, is a photograph a construct or a moment?

Isn’t it both? I imagine it’s both.