Nafplio: The houses were saved, but the residents left

Only about 100 inhabitants remain in the Old Town, as the first capital of the Greek state has gradually turned into a playground for tourists

Kostas Karapavlos is standing in the middle of the hall. The 180-year-old wooden floor creaks with every step he takes. He shows us portraits and old family photos on the walls – his great-great-grandfather was Ioannis Kapodistrias, first head of state of independent Greece at the 1827 Third National Assembly at Troezen and served as the governor of Greece between 1828 and 1831; his great-grandfather was a minister; his grandfather a member of Parliament; his father a mayor. “Before I was elected a municipal councilor, the highest office I had reached was president of the parents’ association. As you can see, the bourgeoisie is gradually declining,” he tells Kathimerini. In addition to being Greek, Karapavlos also has British ancestors.

He lives in one of the oldest houses in Nafplio, full of old furniture and the “ghosts” of relatives. The house was repaired externally 25 years ago and is still holding, but just barely. “The other day the neighbors called me: ‘Run Kosta, a shutter has loosened and is hanging!’ The funny thing is, I had recently changed it. Unfortunately, the new craftsmen do not have the knowledge of the old ones,” he says.

Karapavlos, who is deputy mayor for culture in the Municipality of Nafplio, is one of the few remaining descendants from the city’s old families who still live in their ancestral home. The maintenance costs, taxation and the struggle with the wear and tear of time are unbearable. He knows it, and so does the son who is sitting on the sofa with his girlfriend and their dog: “I hope that when I die you will not turn the house into a hotel or an Airbnb,” he tells the young man. He then adds: “I don’t trust him. He is the first Karapavlos in four generations who did not study the law.” They both burst out laughing. But the truth is that, under the current circumstances, renting out the property in the future will be almost unavoidable.

Led by profit

The architect and engineer Kostas Boudouris works at the archaeological service (and coordinated the restoration of the Castle of Bourtzi, located in the middle of the town’s harbor) and inspects all the building permits in the Old Town, which is protected by the Ministry of Culture.

“Starting from 1998, I have by now entered in 95% of the town’s houses. Of these, 80% have already been restored. Recently, the remaining 20% has started being made into hotels or short-term rentals. Buildings that were languishing due to a large number of heirs have now changed hands two or three times. Such is the financial benefit that even family disagreements, so endemic in Greece, are overcome,” he tells Kathimerini.

Until 2010, when he inspected old houses, he saw, among the owners, descendants of the old families. They didn’t want to destroy the houses and turn them into hostels. But they died and their children left or moved. The descendants had no inhibitions about selling the house, they saw the economic opportunity.

“Thus the town is turning into a Disneyland for tourists, day after day, without any inhibitions. It’s unavoidable. It’s not an easy place to live. It is sunless, has no parking spaces, no elevators and no amenities. Anyone who owns a listed building pays a lot of tax, so they either sell it or use it. The legislation does not give incentives in the right direction because the state is also becoming a big businessman: It knows that tourism will bring it more revenue than housing,” Boudouris explains.

‘The legislation does not give incentives in the right direction because the state is also becoming a big businessman: It knows that tourism will bring it more revenue than housing,’ says architect and engineer Kostas Boudouris

Walking through the cobbled streets on a weekday, one encounters closed shutters and crews of painters and craftsmen working tirelessly on buildings that are now being renovated. They await the couples from Athens who arrive en masse on the weekends looking for suites and a romantic getaway.

As Boudouris explained, the restorations of recent years are made with very expensive materials that will be compensated with by the increase in the price of overnight stays. Soon, he says, the Old Town will have no permanent residents at all and will only appeal to wealthy travelers. This will intensify the existing divide between the new and the old city: On the one hand, the opulence in the shadow of Palamidi, accessible to fewer and fewer people, and, on the other, the modern settlement that has developed next to it, where the modern market and all the services are located. The “embalmed” past with the unsightly present day. Once there was no such division.

Restaurants and bars

Babis Antoniadis, surveyor and engineer, who had run in local elections in the past, is one of those reacting to overtourism. “A constant request of all municipal authorities is to remove the restrictions on land uses and to open cafes and restaurants everywhere,” he tells Kathimerini. “Have they realized that this is how they will drive out the last permanent residents? Who can live next to a bar or above a taverna?”

“It is interesting that the person who architecturally saved the Old Town of Nafplio was not a native. It was archaeologist Evangelia Deilaki, a woman who had a vision to preserve the historical character and wouldn’t back down. She was the one who fought to keep the prisons of Akronafplia from being torn down to become a hotel. Her moral stance led her to clashes with the junta and eventually to her transfer to Volos. Not even the local residents liked her at the time,” he explains.

The foundations

Is there a counterweight to the sweeping influence of tourism? Nafplio has a great endowment of cultural institutions that any other city would envy: the Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation that researches and preserves modern Greek culture, a branch of the National Gallery headed by an active director, and even the local university that has two departments for theater studies (since 2003) and performing and digital arts (as of 2019).

With the president of the latter department, Marina Kotzamani, we visited the building under completion that will house the classrooms from 2025. It’s an old tobacco warehouse in the new town. She notes how difficult it is for the 500 students to find accommodation due to the touristic character of Nafplio, to the extent that some students prefer to come and go on the same day using the intercity bus from Athens. Students present performances and stage works. The irony is that authorities decided to build the Department of Theater Studies in Nafplio, but the town has no proper theater, Kotzamani says.

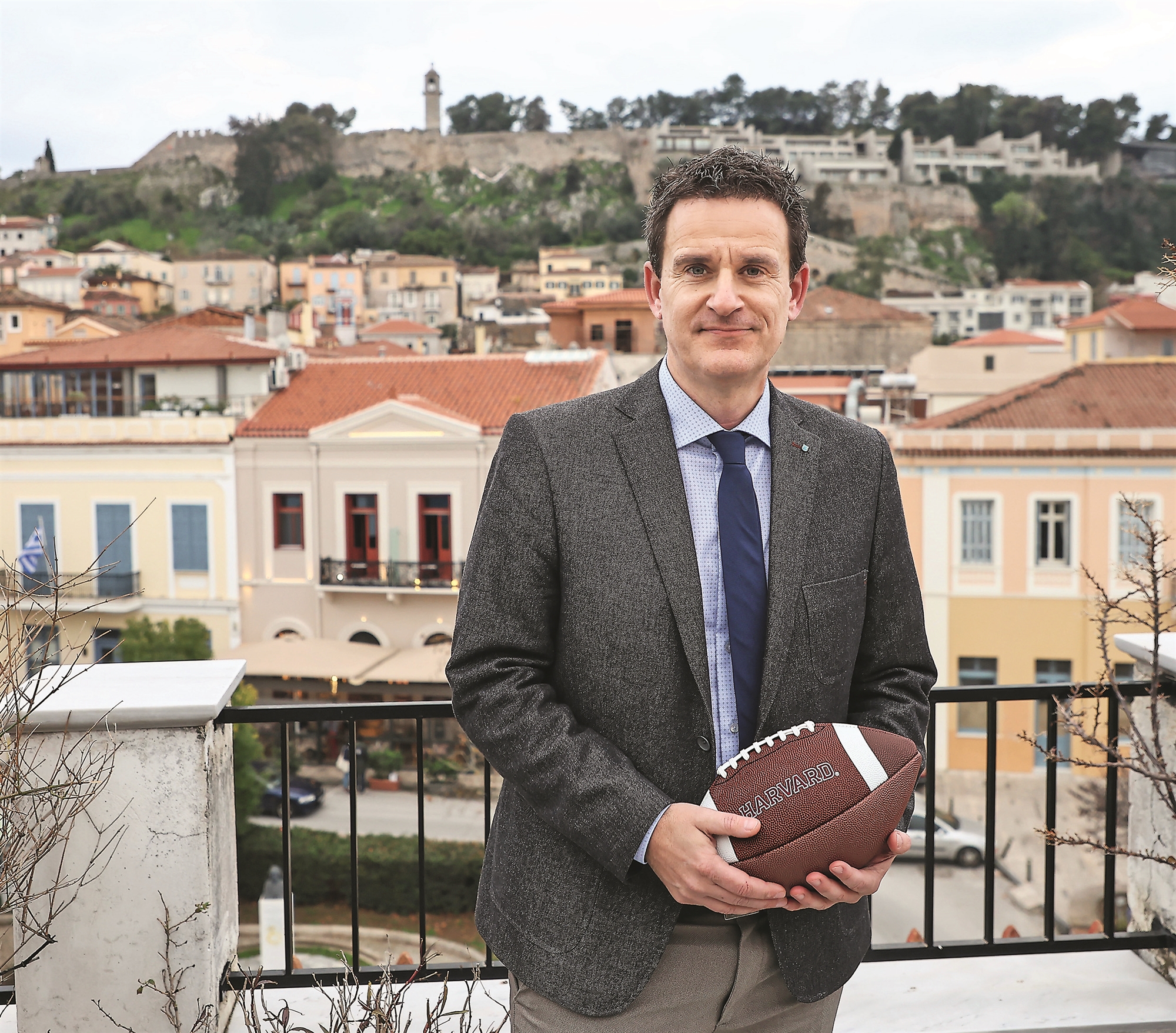

Another serious counterweight is the Center for Hellenic Studies in Greece (CHS Greece), a Harvard global office, which opened in 2008. The center’s Managing Director Christos Giannopoulos, tells Kathimerini that the university had a presence in the region as early as 2002, thanks to its summer school, which remains to this day and perhaps the most popular program of its kind among its students and faculty. Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC was founded in 1961 with a donation from the American philanthropist Paul Mellon. The initiative to create a similar one in Greece was started by Gregory Nagy, an eminent professor of Classics at Harvard University, specializing in Homer and Archaic Greek poetry. “It was originally intended to support university activities and programs related to classical studies and Harvard summer classes,” Giannopoulos says.

“Over time the ambitions became greater, the collaborations with other centers, departments, and offices of the university increased, the activities multiplied. The center today, under the direction of Mark Schiefsky, even helps other American universities that also do programs in various scientific fields by sending their students to Greece, such as Rutgers, and the universities of Washington, Michigan State and Arizona. At the same time, it supports the local academic community and the local society with workshops and more. People have digital access to the entire library we have in Boston through our building. There is also a summer introductory social science program with Harvard students who have been taught such courses and in turn give seminars to high school students from Argolida for two and a half weeks,” he explains.

“It is impressive to see how the children enter this program and how they leave, how much their horizons broaden, how they learn to make presentations, to excel in rhetoric and argumentation and indeed in English.”

He is right. Completely by chance, in 2008 I covered the opening of the center for Kathimerini. Then there was a demonstration by locals against the university. Suspicion and negativity prevailed. Did these disappear after 16 years? Definitely yes. A lady revealed to me that she had taken part in that protest, and now her own child finished his postgraduate research in the center’s library: “I am ashamed of the attitude we took then,” she told me.