Time to change course

We should thank the prime minister, who, in his effort to escape the dead end in negotiations with our creditors, shifted his responsibilities on to the citizens’ shoulders. The referendum, so pregnant with danger, forces us to think (perhaps for the first time) about who we are, where we are, where we’re headed. The fact that the fate of the country may hinge on a single vote shows that we have taken a very wrong turn and that we have to see how we will change direction. It would have been good to have had more than one week to hold this debate, but perhaps then we would have seen even more polarization and uncertainty.

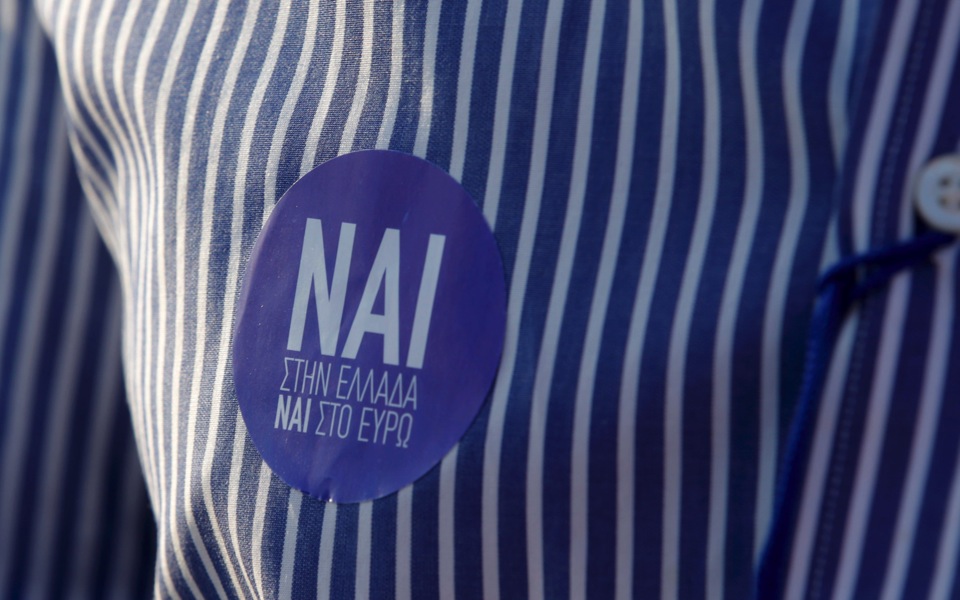

Now we know that on Monday the people will have decided whether they want a solution to our problems while staying inside the eurozone at any cost, or whether they have confidence that the government will achieve something through continuing its policy of conflict with our partners and creditors. Whatever the result, Greece is entering a new era.

The only thing that’s certain is that the immediate future will be very difficult. If the majority votes “yes” the government will have to see how it manages its defeat (seeing as it campaigned so stridently in favor of “no”), and how it will achieve some kind of stability in the economy with our partners, with the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Whether he chooses to call elections or to negotiate with our creditors on a new basis, Alexis Tsipras will have to act in a way that unites the Greeks and also bridges the rift that has opened between the government and our partners.

Experience does not allow optimism, but perhaps a “yes” majority will allow him to get out of the impasse in a way that does not jeopardize Greece’s participation in the eurozone.

A “no” majority will demand even greater political finesse to keep society calm and restore stability to the economy. The passions that have burst out in the past few days, however, will make the government’s task very difficult. Our partners, too, do not hide their lack of enthusiasm to continue negotiations on a new loan deal if it is clear that the citizens as well as the government reject their proposals. It is difficult to understand what Tsipras is thinking when he says that a dominant “no” will strengthen his hand in the negotiations. The bailout program has expired, Greece defaulted on the IMF, the markets were not shaken by our bankruptcy nor by the end of the program, nor by the closing of Greece’s banks and the imposition of strict capital controls. If our hardships do not terrify our partners, how do we expect them to give in to our demands? Through pity?

On Monday, we will all have to see if we can carry on with the polarization and frivolity of past years. The tension of the past few days, the economy’s paralysis and the immediate dangers we face might make us realize that we don’t achieve much when we behave like student activists occupying a building. When SYRIZA was elected in January, many in Greece and abroad welcomed a political force which appeared fresh and untainted. The austerity policy had failed and there was sufficient good will to see what the new government could achieve. The last five months, however, not only failed to result in a new deal but also wrought even greater damage on the economy. And as things became more difficult, the government raised tensions, with senior ministers making a habit of describing people who disagreed with them as the creditors’ lackeys.

We are now at the point where it is clear that neither the past governments nor the present one knew how to improve the country’s fortunes. So perhaps it is time for all parts of the political spectrum to consider their responsibility to work together to create the political culture that they always prevented from developing. Modern Greece has been plagued by division and its development has been warped by the tension between republicans and royalists, populists and reformers, left and right, with variations and sometimes odd alliances. The years of prosperity in the European Union, with the large amounts of money that flowed into the country, papered over the cracks. Everyone appeared to get what he or she wanted, as long as they protested loudly enough. But this also meant that politics continued to be a marketplace where the parties offering the most benefits got the most votes. With the crisis, this relationship was shaken: The mainstream parties that had alternated in power lost ground to opposition parties that outbid them in the popularity stakes but, apart from this, have not appeared capable of governing effectively. Especially at a time when there is little joy to share around in the form of jobs and benefits.

Greece has the talent to get out of this. But the problem is that until now, few were interested in joining politics. It is clear that new people must join the fray, and bring a new mentality with them. Those already in politics must change attitude. Losing the security and prosperity that we had as members of the European Union since 1981 – simply because we cannot work together on even the most basic issues of survival – would be not only a tragedy but a crime of epic proportions.

This dangerous referendum has allowed us the opportunity to learn who we are. But it also shows up our responsibility for where we are and it demands that we work out where we are headed.