The cameras have left Lesvos, but bitterness remains

There were months in 2015 when the eastern Aegean island of Lesvos received up to 6,000 arrivals of migrants and refugees a day. The refugee crisis was the leading news item at the time and harrowing images of those landings traveled across the globe.

Today, the influx has lessened considerably – despite a recent spike – and boats don’t run ashore anymore but are intercepted by Frontex at sea and their passengers dispatched forthwith to the reception and processing center, or hot spot, at Moria – a simmering cauldron of discontent due to overcrowding and squalid conditions.

“If they came out on their boats even today, we would still jump into the water to help them. There is no imagining what we’ve been through, the things we’ve seen. But we are also desperate. Not at the refugees, but at the way the crisis is being managed by the state and by Europe. We have been abandoned. No one helped us when tourism and our businesses collapsed. They turned our islands into prisons, into places of isolation with camps crammed with thousands of people, many, many more than they can handle, living in terrible conditions and becoming a bomb that may go off at any time.”

Dimitris Vatis has a hotel in Molyvos, a pretty village steeped in history with a population of 1,500 on the island’s northwestern coast, whose beaches were a key entry point for the huge inflows of 2015.

“The experience has marked our lives,” says Rallou Kralli, a member of the Molyvos-Petra coordinating committee for the refugee crisis.

“We are the descendants of refugees so we know what it means. But the disorganization, the disruption and the abandonment by the state created fertile ground for every idiot and bigot. I used to be proud of the fact that we had the second-lowest level of support for Golden Dawn at 0.9 percent. In 2015 it reached 6 percent,” she says, referring to the far-right party that has been accused of organizing vicious attacks on migrants.

“Do you know how many nongovernmental organizations we had working on the coast of Molyvos in 2015? A hundred and one – it was like being colonized. They would race each other to the boats so they could get the best picture to post on Facebook and attract donations,” says Kralli. “But the most worrying thing was that we soon had suspicions that some of them were working with the Turkish smugglers. The organizations didn’t follow the inflows, but the other way around. When they moved from Molyvos to the airport, the boats started coming ashore there instead of here.”

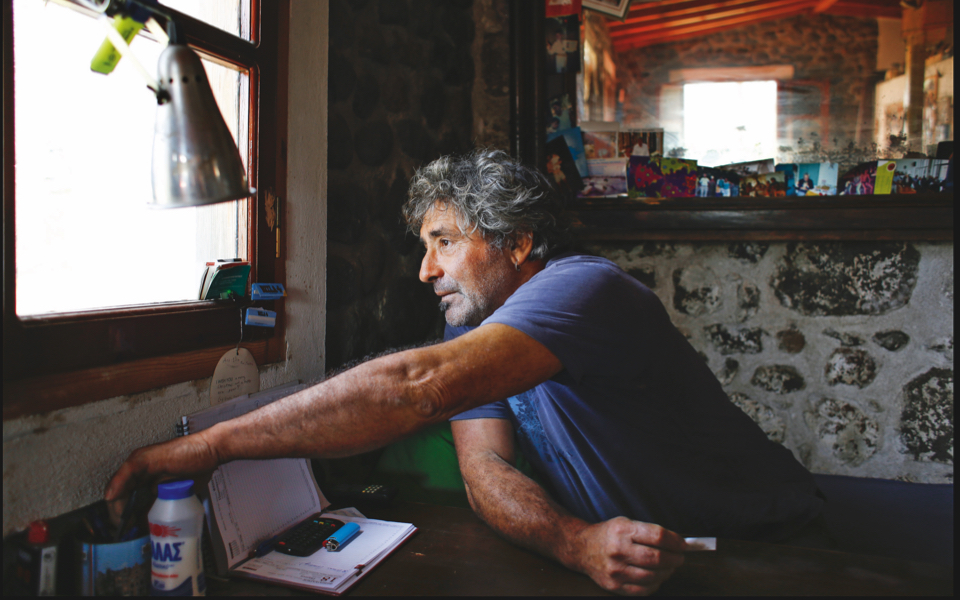

Stratis Kambanas owns a tour boat and is from Molyvos, but in 2015 the only thing he used his vessel for was to “pull those poor wretches out of the sea.”

“I chose to do that, on my own. I didn’t want to take money from any NGOs. There were those who played political and financial games, who got comfortable in agencies and organizations where the money was coming in by the baleful,” he says. “But the civilized world forgets that we also needed psychological and emotional support. I’m reliving 2015 as we speak. I see faces, I feel anger and disappointment. It’s alive inside me. But I would do exactly the same thing if it happened again.”

“I don’t imagine that all NGOs are angelic, as most of the officials in the municipal and regional authorities did,” says Constantinos Maniatopoulos, the director of the Teriade Museum in Vareia, a suburb of the island capital Mytilene. “And the rumors that we benefited from the whole thing are simply not true. Sure, some people found work, rental rates shot through the roof and a few coffee shops and bars did brisk business, but that can hardly be regarded as growth.”

Inflows dropped sharply in the spring of 2016 with the deal between Turkey and European Union states to control trafficking. But that summer was devastating to the islanders in economic terms – at least those who weren’t turning a profit at the expense of the refugees.

“There were some cases of profiteering, but it wasn’t the rule,” says Anna Taxeidi, the owner of a hotel on the Mytilene waterfront – one of the hotels that took in migrants and refugees when others were turning them away even if they had the money to pay for their lodgings. “In 2015, the biggest damage was done by the capital controls, not by the refugees.”

In 2016, however, charter flights to Lesvos nosedived by 70 percent, with a similar impact on hotel bookings.

“The operators who cut their flights destroyed us,” says Vatis. “Demand did drop but not to the extent that they had to cut certain connections entirely. Even if tourists wanted to come they couldn’t. I couldn’t hire back half my staff in 2016. The state failed to protect us, our businesses suffered huge losses and half of them didn’t even open for the summer season. Some people became unemployed and blamed it on the refugees when it’s not their fault. To help the refugees, however, you also need to give some support to the local community in the same way that they say you need to put the oxygen mask on your own mouth before you can help your child on an airplane.”

The summer of 2017 went somewhat better, everyone agrees, and a certain sense of normality returned, but the effects of the influx are far from over.

“We are hoping for a better tomorrow, but we are very skeptical and frightened,” says Vatis.

At Moria, in the meantime, there are around 7,000 people crammed into the camp, which is designed for a maximum of 2,000.

“People are packed like sardines, criminal gangs fight each other, women sleep in adult diapers so they won’t have to go to the lavatory alone at night and now that winter is coming, the conditions are just deteriorating even further,” says Kralli.

“I don’t want to think what it’s like to be a teenager, a girl or an expectant mother in Moria. We have been taking care of refugees for the past 12 or 14 years with whatever funds we could muster, since long before all this happened, and now this lot can’t build 10 camps with all the money that’s coming in from Europe so that people can live with some dignity,” she adds, accusing the government of failing to take adequate measures to improve conditions.

For now, the economy of the island capital Mytilene continues to rely on the refugee influx. They flock to banks at the end of each month to pick up their aid stipend from the European Union, money they use to cover expenses as they look for work and accommodation outside the Moria camp. In recent months, however, Greece has also been dealing with the problem of a large number of economic migrants from Africa, the Middle East and even as far as Cuba, arriving on the shores of its islands in the hope of reaching Western Europe.

“The smuggling networks are extremely powerful and smugglers are doing brisk business; it’s modern-day slavery,” says Kralli. “What we’re afraid of is that the longer the landscape regarding NGOs remains opaque and asylum applications continue at a snail’s pace, the longer the problems will persist. Europe doesn’t care, the government is dragging its feet and the NGOs are desperate to keep their funding lines open. The bitter truth, at the end of the day, is that no one gives a damn about these people.”

* This article first appeared in K, Kathimerini’s Sunday supplement. Photos and research by Nikos Kokkas.