Making AI that can be trusted

The potential and likely consequences of artificial intelligence will be the main focus of a three-day SNF Nostos Conference on August 26-28

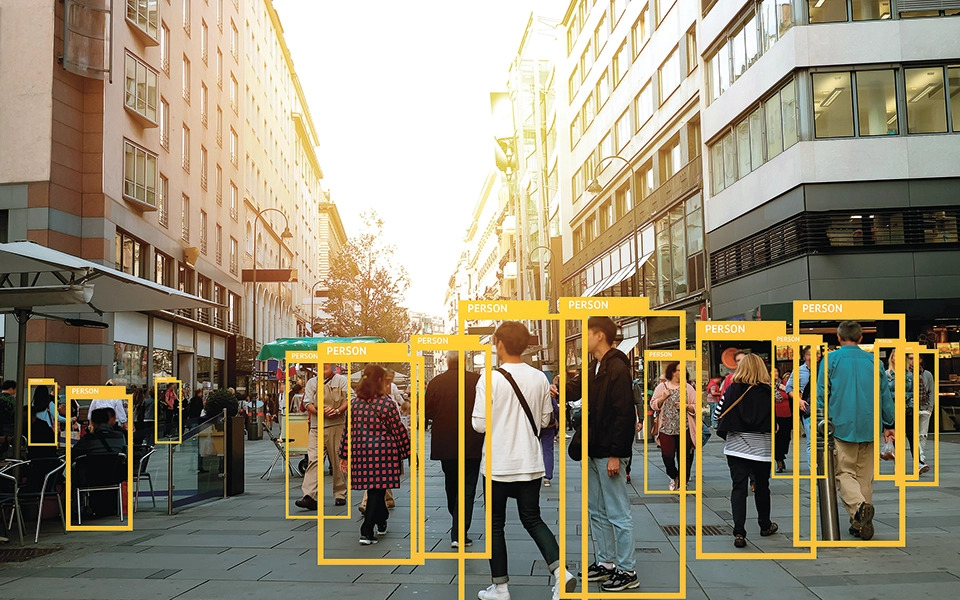

“Few people in the world know better than I do what it’s like to have your life’s work threatened by a machine.” Garry Kasparov’s admission, in his latest book, “Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins,” encapsulates the existential threat posed by artificial intelligence (AI) to its creator. But since February 10, 1996, when IBM’s Deep Blue beat the world champion at chess for the very first time, AI has become an intrinsic part of our day-to-day lives – even if we don’t always realize it. By the time you read these lines, you’ve probably unlocked your phone with facial recognition, gone through your algorithmically curated Facebook feed, or even started a new series on Netflix, recommended on the basis of your previous choices.

A three-day conference organized by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) seeks to redefine our understanding of AI, to the degree that is has been shaped by pop culture and its dystopic – and rather too anthropomorphic – depictions in the realm of sci-fi, with HAL 9000 in “2001: A Space Odyssey” or “The Terminator.”

But that’s not all.

“We don’t only want to talk about artificial intelligence, but also about how artificial intelligence is connected to that thing we call humanity; how it will change the way we see ourselves as human beings,” says Stelios Vassilakis, director of programs and strategic initiatives at the foundation and also one of the curators of the SNF Nostos Conference 2021 “Humanity and Artificial Intelligence,” which will take place on August 26-28 at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC) in southern Athens.

“We’re not talking about a simple technology. We’re talking about a technology that has the potential to completely redefine what it means to be human – with whatever positive or negative consequences that may have,” he adds.

Apart from Kasparov, another 50 or so experts, academics, artists and futurists will be presenting their views and predictions on how AI will transform the human experience, but also the impact it will have on the societies and economies of the future, on the nature of work and the arts.

Vassilakis believes the conversation is long overdue. “Technology is moving ahead at warp speed and the people who handle these tools – as is usually the case with technology – are not taking a moment to think about the consequences,” he says.

Some people are trying. Cases like the removal of two researchers from Google’s AI ethics unit within the space of a few months reinforce the impression that the oversight of research and development departments at Silicon Valley’s tech giants is lacking to say the least. In any case, the ethical issues involved in AI are already very well documented and many of them reflect the all-too-human weaknesses of its designers.

“The algorithms contain bias because algorithms are made by human beings who are biased,” explains Vassilakis.

According to a 2019 study by the University of California, Berkeley, an algorithm that was used by US hospitals to allocate healthcare to some 200 million patients a year systematically discriminated against Black people. Algorithmic systems are also used by companies and educational institutions for evaluating candidates, by banks for assessing their customers’ credit ratings and by law enforcement for predictive policing.

And for anyone not worried enough about AI putting more power into the hands of the already powerful, the technology is rapidly finding applications in the defense industry and in the development of automated weapons systems.

“This, precisely, is where I think all the attention needs to be right now: how these mechanisms will be used and by whom,” says Vassilakis.

Intellectuals like Nick Bostrom, a Swedish professor of philosophy at the University of Oxford, warn that machine intelligence will also be mankind’s last invention as machines will become more capable than we are at inventing new things. And this, in turn, means that the future will be shaped by the preferences of AI. But what will these preferences be? Reason dictates that to achieve a relationship of safe symbiosis with AI, we must first ensure that our value system – the things we hold most dear in life that is – is hardwired into the neural networks of a machine.

If only it were that simple. For the fact is we live in a world where values are often conflicting and, in some cases, incommensurable.

“What, exactly, is our value system and who will prioritize our values when we cannot agree on fundamental issues such as climate change or Covid vaccination?” Vassilakis asks.

But before we start worrying about the impact of automated algorithms and digital super-intelligence, maybe we need to consider more immediate problems.

“I am concerned about what will happen to millions of workers who find themselves without a job because of AI. Every technological revolution so far, including the industrial, ended up creating jobs. This time, however, I believe we will see a paradigm shift. For the first time, we will have to deal with the fact that a technological revolution will not generate more jobs, but will destroy jobs,” says Vassilakis.

In his book “Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow,” Israeli thinker and writer Yuval Noah Harari talks about the rise of “the useless class” and wonders what people with a conscience will do when non-conscious but super-intelligent algorithms do almost everything better.

A year after Kasparov’s defeat by IBM’s supercomputer, a music professor at the University of California in Santa Cruz named David Cope performed a live show of Lutheran chorales in the style of Bach. No one in the audience knew that the music had in fact been composed with a computer code on his household Macintosh.

The assumption irks those who want to believe that the morphological structures we call music, or other art forms, are the purest expression of human emotions, what we often call “soul.” “The question,” Cope told the Guardian back in 2010, “isn’t if computers possess a soul, but if we possess one.”

Vassilakis for his part believes that asking whether an algorithm can be creative is to ask the wrong question. The notion of creation, he argues, is relative: Even an algorithm making something is essentially “creating.” The real question, he says, is all about intentions.

“You could even say that a chicken scratch in the dirt is creative. But an algorithm can, under no circumstances, act with intent in the manner that Bach or Jackson Pollock did. And it cannot possess a conscience. That is precisely where the difference between algorithms and human beings lies.”

SNF Nostos Conference 2021 “Humanity and Artificial Intelligence,” August 26-28 at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC). For more details about the conference and admission protocols, click here.