Pontus, Anatolia and the Dildilian family

A special exhibition at Thessaloniki’s Museum of Byzantine Culture marks next year’s centennial of the famed college’s reopening in the city

“My dear children, I am sorry that I was not able to safeguard for you our family’s wealth; the result of my 40 years of toil has been left behind in Turkey. There I left our sweet home, my studio, in which you sang your first songs, murmured with your innocent lips your prayers; that sacred temple today has become a ruin.”

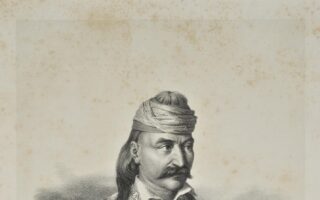

It was with these words in an autobiographical speech in the Piraeus refugee settlement of Kokkinia that Tsolag Dildilian bade farewell to his son Ara as the younger man prepared to sail off to America in January 1928, the memory of being uprooted still fresh.

Six years earlier, on November 1, 1922, with the Greek troops defeated and the city of Smyrna burned to the ground, Armenian photographers and brothers Tsolag and Aram Dildilian and their families in the Black Sea town of Merzifon were given just 24 hours to leave Turkey. They gathered their belongings, as well as hundreds of photographs, glass negatives and cameras, and boarded the SS Belgravia, which had been dispatched by the American Committee for Relief in the Near East. After a perilous journey, they reached the Greek port of Piraeus, along with 2,500 orphans. The surviving members of the Dildilian family ended up scattered across the United States, France and Greece.

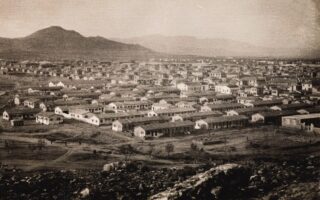

At around the same time back in Merzifon, the Turkish authorities had violently shut down Anatolia College, one of the most influential educational institutions in the wider region, founded by American Protestant missionaries in 1886. Many of its students, as well as the president of the college, George White, were among the thousands of refugees who fled to Thessaloniki. Having brought some 700 photographs documenting life at the school in the good days – photographs taken by the Dildilian brothers – as well as dozens of books, they settled in the northern Greek city and reopened Anatolia College there.

Next year marks the centennial of Anatolia – American College of Thessaloniki and the program of celebrations is being launched with the exhibition “The Photographic Odyssey of the Dildilian Family: From Anatolia to the West,” at the city’s Museum of Byzantine Culture. It is undoubtedly one of the most interesting exhibitions taking place in the context of the Thessaloniki PhotoBiennale 2023 organized by the MOMus Museum of Photography and is a joint production of the Museum of Byzantine Culture and Anatolia College (Department of Libraries and Archives).

Two of Anatolia’s most cherished mementos – the first student register from 1886 and a stone plaque with the initials A.C. from the Merzifon building – along with 70 of the archive’s 700 photographs are being shown together with a selection of material (memoirs, letters, speeches, voice recordings and photographs) from the Dildilian family archive, linking the college to the family that worked as its official photographers for almost three decades, from 1894 to 1921. The exhibits tell us the story of the Dildilian family, from 1872 to 1923, and how it established photography studios in different Anatolian cities, though chiefly Sivas, Merzifon and Samsun. They also shed light on the persecution of the Armenians and Greeks, the terrible losses they suffered, the fight for survival, the ordeal of being uprooted and the effort to build a new life in a new land.

The exhibits from the Dildilian family archive link Anatolia College to the family that worked as its official photographers for almost three decades, from 1894 to 1921

The family history and archive is available to us today thanks to the painstaking efforts of Armen Marsoobian, a professor of philosophy and human rights at the Southern Connecticut State University and grandson of Tsolag Dildilian. He also worked with the museum’s curator, Ioannis Motsianos, and architect Efthymia Papasotiriou to bring us this fascinating story.

But the exhibition also tells us the story of Anatolia College and the role – often vital – it played in the lives of the Dildilians. Five years after the institution was founded, in 1886, Tsolag was brought in to photograph the students and teachers, their activities and all the new facilities being developed (like a school for the deaf, a hospital etc), while he also spent several years operating the Anatolia Hospital’s X-ray machine thanks to his knowledge of processing photographs. His home and studio were located in the same area as the homes of the college’s faculty, American, Armenian and Greek teachers, most of whom were killed in the genocide or in the Greco-Turkish War. Members of the extended Dildilian family attended the college and some were boarders, while three of Tsolag’s sons – like other Armenians – sought shelter in the college during the violence that ended the Armenian and Greek presence in Merzifon. The relationship endured even after both the college and the family were uprooted. Tsolag’s son Ara graduated from the Anatolia College in Thessaloniki in 1928 and went on to become a member of its board of trustees.

World War I

One of the most dramatic episodes in the family’s history took place during World War I. “As 1914 began, the Dildilians and Anatolia College were flourishing,” Marsoobian writes. “Tsolag and Aram’s photographic skills were needed by the local authorities, keeping them at home, away from the front… By the end of the war, Tsolag and Aram would be wearing Ottoman army uniforms, shooting photographs and not rifles… The spring of 1915 brought mass arrests and executions, first of community leaders, soon followed by most adult men. A few were allowed to pay bribes to avoid arrest. Those fortunate few were required to convert to Islam and take Turkish identity. On June 22, 1915, the deportation orders were announced and by August the last Armenians, including many faculty, staff and students of the college, were gone. Most perished before reaching the concentration camps in the Syrian desert. Under the threat of deportation, the family converted to Islam and were given Turkish names. They maintained their Christian faith privately at home, behind shuttered windows and high walls. Digging deep tunnels and securing hiding places, they rescued and hid upward of 40 young men and women in their homes over the course of the next two years… For Tsolag and Aram, the pretense of the ‘Islamized’ and ‘Turkified’ Ottoman army photographers was quickly discarded [at the start of the Greco-Turkish War]… The Dildilians turned much of their full-time focus to the orphans. The Dildilian cameras would once again be active, but this time capturing images of the orphans and the plight of the survivors.”

When the Dildilians and other Armenians first arrived in Greece, they were put up at Zappeion Hall in downtown Athens, before being transferred to refugee camps, where they captured scenes of the humanitarian crisis. Their prospects for emigrating to the United States, where other members of the family had fled, were not very good, but Aram made it thanks to having studied photography in America. Tsolag settled in Greece and opened a studio with his eldest son, Humayag, first at the camp and then in Kokkinia, in the middle of the migrant district. After Tsolag’s death in August 1935, Humayag and his sister Alice opened a modern studio at the port of Piraeus. As was their custom even in Anatolia, the Dildilians did not only do portraits in their studio. They photographed monuments and sites, they captured the explosions of the Santorini volcano in late 1925 and early 1926, and recorded the devastation from the Corinth earthquake on April 22, 1928.

The business survived the German occupation – “The first year of the war business was not good, but very often [customers] came from the villages, and we traded pictures for food – oil, corn, flour, especially olive oil and olives,” wrote Alice.

“This is where the Dildilian story is unique and unlike most diasporan Armenian stories. Many such families count themselves lucky to have a few photographs and orally conveyed stories that were snatched from the flames that marked the end of Armenian life in their historic homeland. Our family is privileged to have more, much more, that allows us to reconstruct what their lives were like,” writes Armen Marsoobian. “‘For no man is witness to him that already believeth, and therefore needs no witness; but to them who deny or doubt, or have not heard it,’” he adds, quoting Thomas Hobbes.

“The Photographic Odyssey of the Dildilian Family: From Anatolia to the West” is on display at the Museum of Byzantine Culture through February 11, 2024. For opening hours and other details, visit mbp.gr.