A Greek archaeologist’s dig into the Elgin archive

Tatiana Poulou recounts how research into a necklace put her on the trail of the British lord’s Italian agent in Athens

It was an August morning in 2014 when Greek archaeologist Tatiana Poulou walked across the gardens to the entrance of Broomhall House, the family seat of the earls of Elgin in Scotland. “I was nervous, I admit. I was about to study his unpublished archive and the only thing I was interested in was the historical truth – whatever it may be,” she tells Kathimerini nearly a decade later.

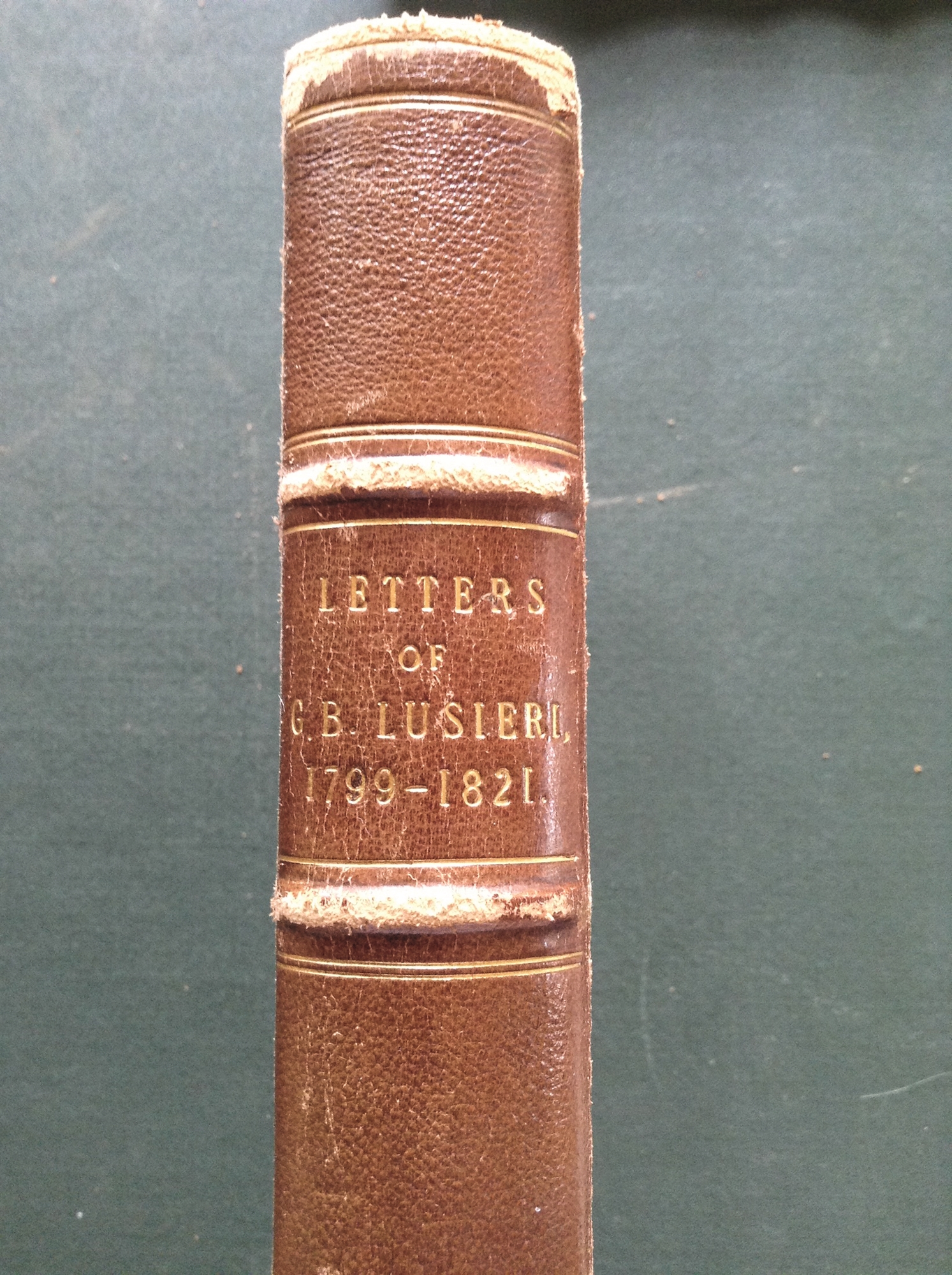

Poulou was received by Andrew Bruce, the 11th earl of Elgin, his wife and one of their five children. They were nervous too, they told her later, but didn’t show it. They took her to a room that had been arranged for her visit, with a big wooden table containing seven volumes with the 500 letters exchanged between Thomas Bruce, the seventh earl of Elgin, and his agents, and handed her a pair of white gloves to wear while handling the material. The Greek archaeologist was there to research the history of a single piece of jewelry, but, as is often the case, this led her to other startling discoveries concerning the removal of the Parthenon Sculptures from the Acropolis.

The necklace

The story she shares with Kathimerini actually begins earlier, in 2002, and, coincidentally, with a project related to late culture minister Melina Mercouri’s vision for the unification of Athens’ archaeological sites. Specifically, it starts with the discovery of three graves from the Geometric period on Philopappou Hill, thanks to excavations for a new fence.

Nine years later, the official responsible for the archaeological site on Philopappou called Poulou into her office and asked her to examine the graves as the archaeologist responsible for the excavation did not have the time. “I had been under the impression that it had yielded just nine vessels, so I was surprised to find 105 fragments of gold jewelry that had been buried alongside a 13-year-old girl,” Poulou explains.

She spent days trying to piece the fragments together and ended up with a likely combination. She photographed it and headed to the library, where she discovered material on a necklace that looked almost identical to the one she had pieced together – an exceptionally rare occurrence. To her even greater surprise she discovered that this particular piece was on display at the British Museum and belonged to the Elgin collection.

In 2013, at a conference in Brussels, Poulou met Dyfri Williams, a pre-eminent authority on the Elgin archives, and showed him photographs of the two necklaces. “It’s from the Lusieri dig,” the expert promptly answered. Poulou did not know anything at the time about the Italian artist, Giovanni Battista Lusieri, whom Lord Elgin had sent to Athens to act as his agent. Williams went on to say that Lusieri had been responsible for severing the marble sculptures from the Parthenon and had also carried out excavations in the area, probably finding the necklace near Philopappou Hill.

“As soon as I returned to Athens, I rushed to the British School and asked the director at the time, Catherine Morgan, to help arrange it so I could go to the British Museum and study the piece,” Poulou recalls. Warm to the idea from the start, Morgan saw it as an excellent scholarship opportunity not just for a research visit to the museum, but also for the Elgin archive in Scotland. They got in touch with the 11th earl and he accepted. “It had never crossed my mind that a Greek archaeologist would have the opportunity to study the archive,” says Poulou.

‘Lusieri caused an enormous amount of damage to the Parthenon. I had heard Manolis Korres speak on the subject, but it is completely different to read the words of the person who wrought such destruction’

Closed archive

Under British law, the archive is private and remains unpublished in its entirety. Access to it was shut down for 35 years following the publication of a book in 1967 by a researcher of the archive that was particularly critical of the seventh earl of Elgin. Poulou became the second Greek, after Elena Korka, today honorary director of the Ministry of Culture, to study it.

Poulou was in for another shock when she saw the handwritten 19th century letters. Despite the initial difficulties in reading them, she was lucky that they were in French (she studied in France) and that Lusieri had legible handwriting. “I was able to read them easily after a day. My time there was so full, I didn’t even take lunch breaks,” she says, recalling how Lady Elgin would drive her to the seaside village where she was staying every afternoon at 5 o’clock sharp.

After spending a few days at Broomhall, Poulou realized that the historical residence contained “a lot of Greece,” from the plaster moldings on the walls styled after the floral decorations of the Erechtheion to a line of furniture inspired by the roof of the Parthenon. In one room, she spotted a replica of the so-called Elgin Throne, which the family sold to the Getty in 1974, along with a multitude of antiquities which Lusieri had sent Elgin after 1816 and the sale of the collection to the British Museum. These included an ornate sarcophagus that the Italian artist had found in Athens on March 6, 1811, and described in great detail in one of his letters.

The family invited Poulou to lunch one Sunday. They spoke about the family’s long history, how the current earl – now a centenarian – was injured in the Normandy landing, and other general topics. “We never got onto the subject of the sculptures or the seventh earl of Elgin, though at some point, the eldest son told me that if Lusieri had not done what he did, his ancestor would have not only salvaged his marriage, but also his reputation,” Poulou recalls.

The family admitted to feeling cursed by the issue and becoming very upset whenever the issue of the sculptures’ repatriation comes up. The son also regretted that his father often comes under fire over the matter. “He doesn’t deserve the bullying he’s been subjected to,” he told her.

Before leaving Broomhall, Poulou gave the family a written report of her findings and promised to keep them abreast of any publications or lectures related to the archive. True to her word, in 2016, 2019 and again last October – when she spoke at an international conference on the North Slope of the Acropolis at the Paul and Alexandra Canellopoulos Museum in Athens – she translated her presentation and sent it to them.

The Lusieri factor

In her presentation at the Canellopoulos Museum, Poulou referred to some of the letters, which contain chilling details of Lusieri’s actions during the three years that he had access to the Acropolis. When his team was blocked from entering the site the first time, he asked Elgin to secure a firman from the Ottoman authorities that would be “written in such terms so as to avoid any further difficulty.” He later wrote to Elgin saying how the money he had sent helped them “excavate and remove” objects. In other letters, he asks for tools like saws to “reduce the weight” of big sculptures that could not be shifted in one block. In another, he admits that the team would not have made any headway without Elgin’s “money, presents and influence.”

“There were times in Broomhall when I wept as I read the letters,” Poulou tells Kathimerini. “Lusieri caused an enormous amount of damage to the Parthenon. I had heard [archaeologist] Manolis Korres speak on the subject, but it is completely different to read the words of the person who wrought such destruction. This was not your usual research. It did not concern a vessel or some wonderful statue. This is a matter that is directly related to our national identity, to the destruction of a national monument and, of course, to the repatriation demands. As archaeologists, we may not get involved in the politics of the issue, but we know that some of these letters constitute a valid argument [for the Greek side],” she notes.

Poulou’s work is not done. In the decade since her visit to Scotland, she has located Lusieri’s house in Athens (in the Anafiotika district above Plaka) and confirmed that 120 vessels that had been stolen from his house and reached Napoleon Bonaparte are still missing. She has already traveled to Naples once on their trail and needs to go again. She is also planning visits to London, Bristol and Marseille to continue her research.

“What is such a shame is that as archaeologists working in Greece, this kind of research is very challenging to conduct. It takes time and money. The scholarship, and especially the British School’s support, was incredibly valuable, but I still had to cover a large part of the expense on my own,” says Poulou.

The archaeologist is clearly on a mission; that much was obvious in her lecture last October, in the emotional way she spoke of Lusieri’s actions, but also of lesser-known aspects of his life. With time, she has come to see the Italian agent as both a perpetrator and a victim. “He served Elgin so loyally; he stayed with him all the way to his deathbed, despite all the drama in his own life. He wrought an enormous trauma on Greece which we are trying to heal with the statues’ return, but he also came to a very tragic end, all alone, abandoned by everyone and penniless. He was following orders, but it is equally clear that without him, the Elgin collection would never have come to be,” says Poulou.