Imia, behind the scenes

Testimonies from key players shed light on unseen details of the standoff 28 years ago

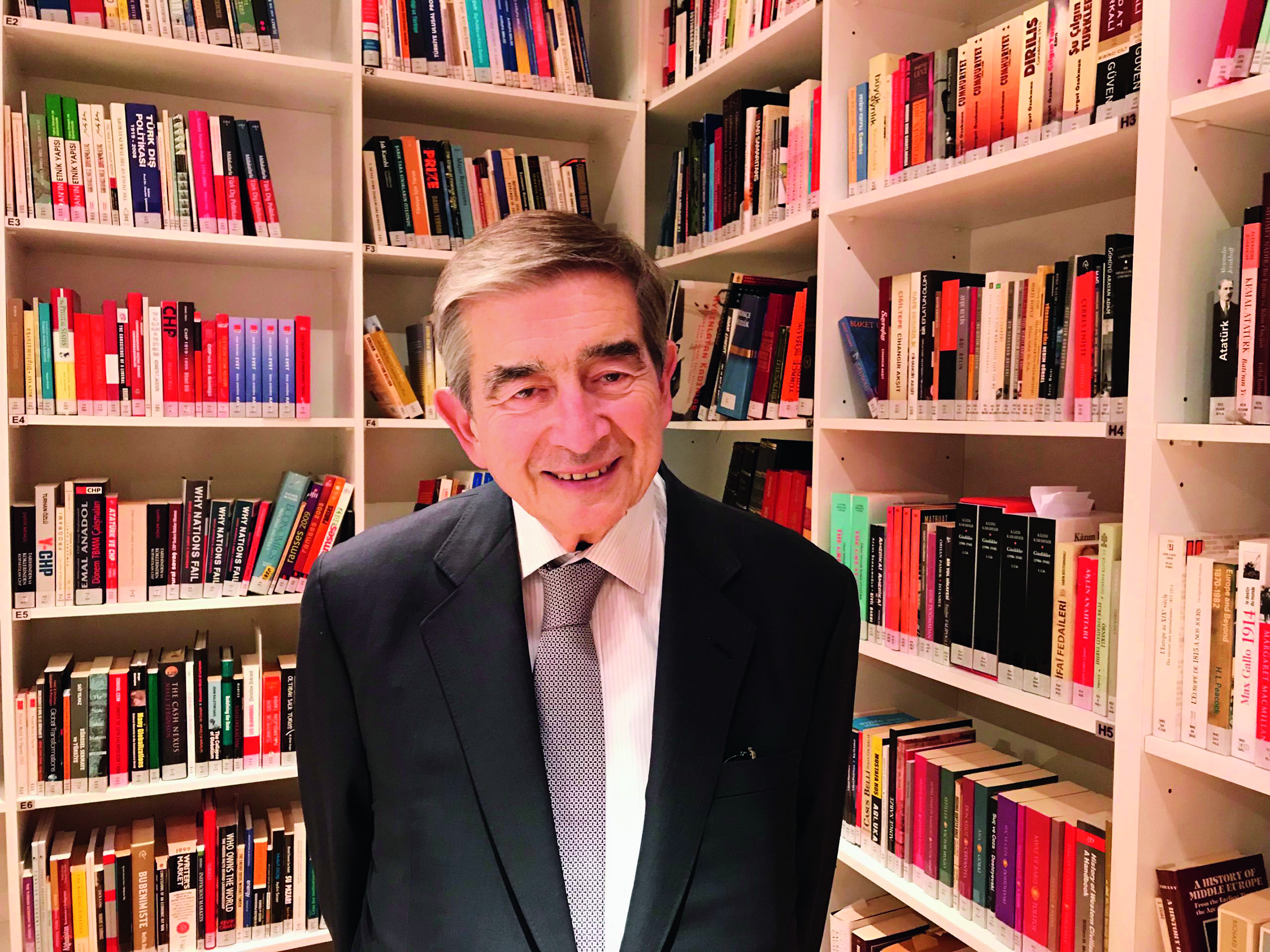

January 31, 1996. The peak of the Imia crisis leads to the crash of the Agusta Bell PN21 helicopter and the death of three Greek officers. Twenty-eight years later, Kathimerini attempts to shed light on the unknown background of the crisis and the causes that brought the two countries to the brink of war. Through the exclusive testimonies to Kathimerini of two of the protagonists of the crisis, the then-Greek ambassador in Ankara Dimitrios Nezeritis and former Turkish deputy foreign minister Onur Oymen, unknown details about the crisis and elements of the “war of diplomacy” are revealed.

In a chronology of events divided into seven parts, Ambassador Oymen – a close associate of then prime minister Tansu Ciller and the “real boss at the Foreign Ministry,” as Ambassador Nezeritis describes him – reveals unknown aspects of Turkish foreign policy, while the Greek diplomat describes the real intentions of the Turkish leadership and the subtle manipulations of the Greek mission through dialogues that were held behind closed doors.

Act One: The grounding of the Figen Akat and Ankara’s plans

At the end of 1995, Andreas Papandreou’s failing health led him to hand over the premiership to Costas Simitis. At the same time, on the other side of the Aegean, the Turkish elections of December 24 – one day before the Turkish cargo ship Figen Akat ran aground in shallow water off the two eastern Aegean Greek islets that comprise Imia – resulted in the electoral defeat of Ciller, who, despite the shocks and reactions, remained in the leadership of the country until a government was formed.

At the end of 1995, Andreas Papandreou’s failing health led him to hand over the premiership to Costas Simitis. At the same time, on the other side of the Aegean, the Turkish elections of December 24 – one day before the Turkish cargo ship Figen Akat ran aground in shallow water off the two eastern Aegean Greek islets that comprise Imia – resulted in the electoral defeat of Ciller, who, despite the shocks and reactions, remained in the leadership of the country until a government was formed.

As the Turkish former deputy foreign minister notes: “When the crisis broke out, it was a period when there was a change of government in Turkey and Greece, and our foreign minister had recently been replaced. Consider that there were six changes of ministers in the Foreign Ministry in two and a half years. So it was not the most stable period.”

According to Honorary Ambassador Nezeritis, “the Turkish side had studied very carefully when it would cause the crisis because at that time Costas Simitis had not yet been elected. Andreas Papandreou was still prime minister, but he was ill in hospital. In Greece, governments are prime minister-centered, so at that time the country was in a state of limbo. This gave Turkey a very good opportunity to move forward in this crisis, which, as the then chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Turkish Parliament revealed to me, had been planned since the summer of 1995.”

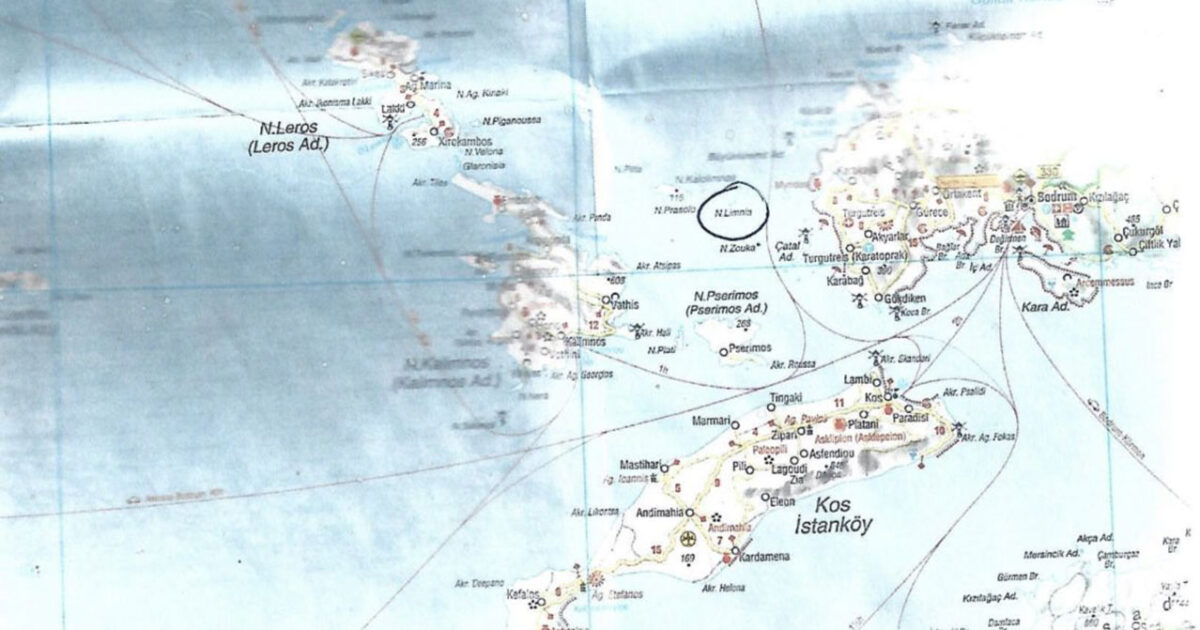

“When the Figen Akat incident happened,” the Turkish diplomat claims, “we realized that Kardak [the Turkish name for Imia] was registered in local Turkish government documents as part of Turkish territory, and we consulted international maps that show Kardak within Turkish territorial waters. We then consulted other agencies that might be informed about the history of the islands and discovered that there was absolutely no doubt about the affiliation of Kardak. But at that moment we did not want to create a political problem, because the issue of the ship had been resolved and there was nothing we could do.”

as part of Turkish territory, and we consulted international maps that show Kardak within Turkish territorial waters. We then consulted other agencies that might be informed about the history of the islands and discovered that there was absolutely no doubt about the affiliation of Kardak. But at that moment we did not want to create a political problem, because the issue of the ship had been resolved and there was nothing we could do.”

Ambassador Nezeritis also describes a climate that did not bode well for escalation. “When the incident with the Figen Akat happened, our embassy secretary, Mr [Ioannis] Papameletiou, went to the Turkish Foreign Ministry and made the appeal. The Turkish response was, ‘Yes, we will tell the captain to accept to be detached from the Greek authorities.’ The point is that if the story had stayed there, then there would have been no follow-up,” he recalls.

Act Two: The dispute over the status of islands

In the days that followed, the Greek Embassy in Ankara was in regular communication with the Turkish Foreign Ministry, as the Turkish side disputed the Greek status of Imia. As the former head of the Greek mission recounts, “A few days after the incident with the Turkish cargo ship, Turkey sent a verbal note to the Greek Embassy saying that ‘the islets are Turkish and are registered in the Turkish land registry of the Bodrum prefecture.’ The Turkish notice prompted an immediate response from Greece. Besides, we could not let a verbal announcement like this one go unanswered, as it would mean tacit recognition of the Turkish side’s claims.”

On the other hand, Oymen describes the early diplomatic crisis and refers to the Turkish objections.

“We received a verbal note from the Greek Embassy in Ankara claiming that Kardak was Greek territory. Your diplomats visited our ministry, spoke with me and Minister Baykal, put forward their arguments and we explained to them that according to all information, there is no doubt that the islands were Turkish territory and that for us there is no discussion about it. Then our minister visited the prime minister and stated the same. So for us, the problem was already closed.”

Act Three: The ‘war’ via the media

The new year (1996) brings Greece under the leadership of Costas Simitis. The then mayor of Kalymnos, Dimitris Diakomichalis, informed that the Turkish authorities were disputing the status of Imia, went to the eastern islet (Small Imia) on January 25, 1996 and hoisted the Greek flag. The mayor’s action was described as “provocative” and “hostile” by the Turkish press, with journalists from the Hurriyet newspaper going to Small Imia and raising the Turkish flag, subverting the Greek flag.

As Ambassador Oymen argues: “The Greek press wrote several articles on the issue and this created a public reaction in both countries. First, the mayor of Kalymnos brought a Greek flag and went to Kardak and placed it there, and then the Turkish press reacted and wrote articles on the issue. This led some Turkish journalists to go to the islet and take down the Greek flag and put up the Turkish flag instead. This whole issue caused a big political crisis.”

In contrast to Oymen’s account, Nezeritis notes: “It was a given that at some point the Turkish claims would be leaked to the Greek press, as Turkey, through the verbal note, was officially challenging not only the status of Imia, but the entire status of the region, as it had been drawn up through the Turkish-Italian agreement on the delimitation of the border in the South Aegean, at the height of the Dodecanese. You should know that a Turkish diplomat, a partner of Ciller, had said that ‘this is something we have been preparing since the summer.’”

Between January 25 and 28 the proxy “war” escalated, with the political leaders taking up “battle positions” and the two prime ministers crossing swords in the communication arena. The Greek Embassy in Ankara was on alert, with the Greek staff preparing to rebut Turkish claims. “Around the end of January, a few days before we reached the height of the crisis, I visited the Turkish ministry and spoke with Minister Baykal,” Nezeritis recalled. “Baykal was very calm and not at all upset by the situation. We sat side by side and he read me the verbal note, which was a whole transcript of all the Turkish arguments, written in English.”

“I must tell you,” the Greek ambassador added, “that as I was sitting next to him, I took a look at the text he was reading. I noticed that in some places above the English, he had translations of words written in Turkish. The man did not know English too well to know exactly what he was saying to me.”

“The instructions I had received from Theodoros Pangalos [the then Greek foreign minister],” adds Nezeritis, “were to go to the ministry and see all the top leadership to try to defuse the crisis, arguing that the buildup of naval forces in the area was causing a risk of conflict. After the meeting with Baykal, I went and met with Oymen and he told me certain things, which I took back to Athens. Oymen summed up our discussion with the phrase ‘Dear Mr Ambassador, things are very serious. This crisis must be controlled. Gather your forces, gather your flags, and withdraw.’ This happened on the morning of the day of the crisis, and by 3-4 o’clock in the afternoon, Oymen had disappeared because he was at the meetings preparing for the invasion of Imia. Let us have no illusions, Oymen was the real boss in the Foreign Ministry.”

At the same time, Oymen describes the events as follows: “The Greek government acted formally, sent troops to this islet, and also put up a Greek flag. Mr Pangalos told us that this flag would never be withdrawn and the troops would never return. This caused a real political crisis between the two countries, and in the ministry, we discussed how we could react. So we used all diplomatic ways and means to communicate with the Greek government.”

In conclusion, the Turkish ambassador described the scene with the Turkish staff. “The position of Mr Pangalos left no room for maneuver for anyone,” he adds: “Therefore, we discussed it with the government at the highest level and the government decided that in case the Greeks do not accept the diplomatic way of solving the problem, the only way to dissuade the Greek government is by sending troops not to the ‘small islet’ where the Greek troops were stationed, but to the other rocky islet (West Imia), avoiding any confrontation, and try to solve it through diplomacy.”

Act Four: The deployment of troops and the role of diplomacy

From the first days of the crisis, the American forces were watching the events. Richard Holbrooke, the American diplomatic officer in charge of European affairs, was in open contact with the foreign ministries of the two countries. “I already knew Richard Holbrooke from our previous jobs,” Oymen says. “At around 3 a.m. (January 31) he called me and said: ‘We heard that Turkish troops are about to land on Kardak. Is that true? Because such an act really creates a serious situation.’ I replied, ‘You have the wrong information.’ ‘Now I am relieved,’ he said, and I replied: ‘Do not be relieved because our troops are already there. They are not planning to land, but they are already there because there is no possibility of solving the problem through diplomacy and the only way to persuade the Greek government to withdraw their troops is to take back their flag.’”

“Also on the line, apparently, was Mr Pangalos. We had four or five telephone conversations with Holbrooke. At the end of the night, Holbrooke said to us, ‘In case the Greek troops are withdrawn and the Greek flag is removed, the Turkish government should be ready to take back its troops and its presence.’”

One hour earlier [2 a.m.], the Greek ambassador had been notified of the landing of the Turkish special forces on the western islet. As he recounts, “At 2 a.m., the director of the press office, Mr Stathoulopoulos, called me and informed me about it, so I called the rest of my colleagues, explained the situation, and gathered everyone at the embassy.”

At the Turkish staff, meetings were ongoing, and Oymen was at the center of the contacts. “In those hours I spoke with the minister and with my superiors, who stressed that this was our initial position, namely the withdrawal of forces and flags,” he says in his account to Kathimerini. “It was not our intention to invade any island or to send troops to any island in that region. But we were forced by the Greeks to take such an action,” he claims.

According to the Turkish diplomat, “by the first hours of the next day [February 1] we had returned to the previous situation in Kardak, there was no further confrontation and no problem, while the Greeks withdrew their troops and we took back ours. So, there was no longer a Greek flag planted and that brought us back to the status quo ante.”

Act Five: The PN21 helicopter and the sacrifice of the three pilots

The Imia crisis was marked by the loss of the three members of the crew of the PN21 helicopter, Lieutenants Christodoulos Karathanasis and Panagiotis Vlachakos and the chief pilot Ektoras Gialopsos. Honorary Ambassador Oymen and former head of Turkish diplomacy notes: “The downing of the helicopter was obviously an accident. We are very sorry for the pilots, for their families, and for the Greek government. Our understanding of the incident and the information we have is that it was an accident. It happened during the night and they probably had problems with night vision equipment. I do not know more as we have no report of the accident from the Greek side, but this crisis was an unnecessary situation and it is a pity that the three pilots lost their lives.” Asked about the reaction to the news of the helicopter crash, Nezeritis said he wished to remain silent.

Later in the discussion, the Turkish former deputy foreign minister was asked if the soldiers had been ordered to attack or shoot down the Greek aircraft: “The helicopter was not shot down. We had no such policy, no such intention, and of course no such instructions were given to our soldiers.”

Act Six: The de-escalation and withdrawal of troops

According to expert assessments, political instability within Turkey and the weakness of Ciller’s government, which led to a coalition with Necmettin Erbakan in June 1996, encouraged the externalization of tensions in the Aegean.

Ambassador Oymen rejects this version and argues: “This crisis was not a Turkish initiative; we did not create the crisis and we tried to resolve it through diplomacy from day one. But Mrs Ciller mentioned at the end that Greek troops would withdraw and take back the Greek flag. So that is what she said. But again, I say that the Turkish government was not the initiator of this crisis and this problem.”

“Frankly speaking,” the Turkish diplomat adds, “I did not expect a full-scale war, because I was quite sure that the Greeks would realize that Turkey is determined, and they did what we expected them to do, which was to withdraw their troops and their flag, and so we did not create any additional problems in the press or in public opinion. So, my assessment is that it was a serious crisis at the time, which is now over.”

In his own assessment of the gravity of the Imia crisis, Nezeritis assesses the situation as “sufficiently serious,” stressing: “Look, we were quite close to war and the moments were critical, but in my opinion, there would not be a total war. The Turks were seeking to have a localized conflict, sink a couple of ships, kill about a hundred people, as the Turks don’t count people very much, and then put pressure on both sides for talks.”

Act Seven: Greek-Turkish relations in the ‘post-Imia’ era

Concluding his discussions with the two diplomats, Oymen stressed that the Imia crisis did not end in the Aegean Sea, but moved to the diplomatic chessboard. “Look, after the crisis was over, the Greeks continued to cause problems, as they decided to block the European Union from providing the aid that was supposed to be provided to Turkey to compensate for the customs union. Thus, a new situation, a new problem between Turkey and Greece was created, which lasted quite a long time.”

In the same vein, the Greek ambassador who handled the crisis and the relations between the two states after its conclusion stressed to Kathimerini: “Greek-Turkish relations since the time of Imia have been permanently bad. We were in a period of constant crisis, as the gray zone policy emerged after Imia. During the four years I was in Turkey, relations between the two countries went from bad to worse. However, it must be stressed that Turkey did not achieve its intended objective in Imia, namely a negotiation between Greece and Turkey on the status of the Aegean.”

“To sum up, the conclusion we have drawn,” the Turkish diplomat said, “is that everyone should learn lessons from such crises and realize that the only way to solve Turkish-Greek problems is not through a fait accompli or through provocations and attacks, but to create a better atmosphere between the two countries through dialogue, while reconciliation between Turkey and Greece can also come through the help of the NATO secretary-general of the day.”