The pendulum and the extremes

On the day that a group of far-right military officers seized power in Greece, in the early hours of April 21, 1967, Kathimerini’s then-publisher, Eleni Vlachou, had the journalistic wherewithal to press the button on the tape recorder on her desk. “Not to be pessimistic, but we won’t be getting out of this predicament anytime soon. And the right, the so-called right… It’s done for. Done!” she is heard saying on the tape. Containing the various conversations that unfolded at the paper between the reporters who managed to make it in that day, this tape is a vivid testimonial on the country’s modern history.

When Vlachou uttered those words, she obviously had no idea how prophetic they were. The information in the newsroom at that moment was piecemeal; all they knew was that there had been some kind of military uprising. Her power of insight, however, allowed her to see what was coming. That violent interruption of the country’s smooth democratic evolution is something we have paid for dearly. The equally violent – and justified, to a large degree – reaction to the junta has also come at a steep price.

Greece went from an authoritarian regime that sent its opponents into exile to an unfettered sense of entitlement and the erosion of the country’s institutions and state apparatus in the name of ersatz equality and a twisted form of unionism. The pendulum swung from too far to the right, to too far to the left.

The right may not be bankrupt in the way that Vlachou meant it, because it went on to govern for several years. But its reputation was tarnished and it did lose the ideological high ground and the resonance it had with dynamic sections of society. Every move it made came with some sort of penance, as if it had to apologize for its ideological leanings. Indeed, there were times when it was hard to tell the right from the left.

The reaction to the dictatorship, however, also seemed to erase logic and a sense of proportion. It is the reason why our universities are a graffiti-covered mess, why lengthy sit-in protests, street fights and riots are tolerated. The rotten part of the academic establishment is another part of the same problem, the product of the quid pro quo mentality and the mediocrity that was imposed at the country’s universities in the name of another ersatz step toward democratization.

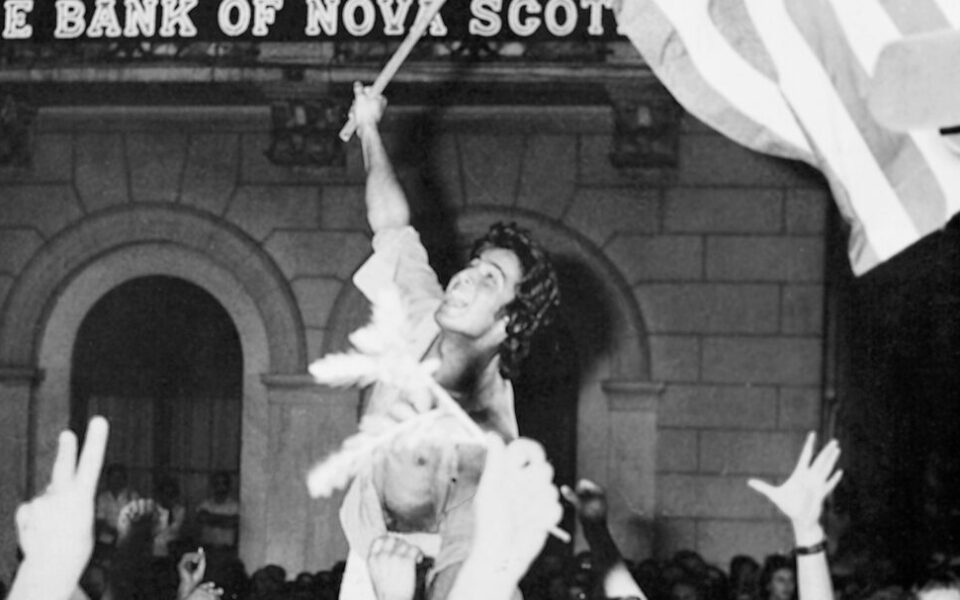

As Greece celebrates the 50th anniversary of the restoration of democracy after the fall of the dictatorship, or the Metapolitefsi as the process is known here, the pendulum is once again moving to the right, and fast. SYRIZA’s mishandling of the economic crisis played a part in debunking many myths about the left and making Greeks adopt a more pragmatic point of view. Public discourse is also moving to the right, sometimes to extremely toxic and vulgar extremes. But this is what happens when the pendulum starts swinging too far in either direction.

Anyway you cut it, though, 50 years has been a long time to overcome the hang-ups from that period and to close certain chapters of our history. Of course, anyone who insists on harping on about the past, who is stuck in 1944 or 1974, will remain on the fringe. And anyone who doesn’t respect history will bear a huge responsibility if the pendulum swings too far to the right this time.