Mapping crime scenes to solve disputed cases

A video by Forensic Architecture pertaining to the events on September 18, 2013, when rapper Pavlos Fyssas was stabbed to death in the street by a self-proclaimed Golden Dawn supporter in the Keratsini district of Piraeus, constitutes one of the most damning pieces of evidence in the ongoing trial against the neo-Nazi party, whose leadership is accused of ordering that attack, as well as others.

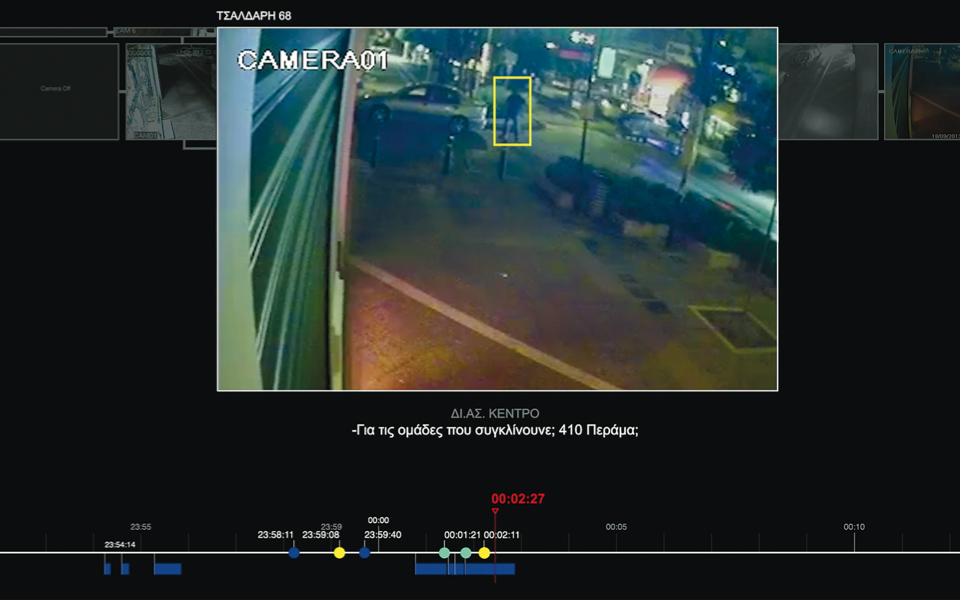

The 43-minute audiovisual presentation and accompanying report by the independent research group, which is headquartered at Goldsmiths, University of London, was presented to the court last September and filed as evidence. It has also been posted online. In it, Forensic Architecture researchers have reconstructed the events of that fatal night, using maps of the area, CCTV footage and recordings of communications between police and emergency services.

They have also identified and cross-checked the testimony of witnesses and analyzed the metadata of private security cameras in order to build a precise timeline and shed light on the sequence of events.

According to the report, “the investigation established that members of Golden Dawn, including senior officials, acted in a coordinated manner in relation to the murder, and that members of Greece’s elite special forces police, known as DIAS, were present at the scene before, during and after the murder, and failed to intervene.”

Forensic Architecture is a multidisciplinary team made up of architects, visual artists, photographers, filmmakers, journalists, archaeologists, lawyers, software designers and programmers and experts on platforms similar to those used in the design of video games.

The agency was founded in 2010 by British-Israeli architect Eyal Weizman, a professor of spatial and visual cultures and founding director of the Center for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths. It investigates human rights and environmental abuses, as well as war crimes, and has been active in countries ranging from Indonesia, Pakistan and Syria, to Germany, Turkey, Ukraine and Greece.

Its investigators use data drawn from a wide variety of sources, ranging from CCTV footage to aerial shots from Google and social media. Using spatial and multimedia design technology, they map out their area of investigation in detail, and test witness testimonies and public narratives in the context of 3D architectural models, interactive maps, videos and touring platforms, in order to uncover the truth and help human rights groups, NGOs and other agencies in their investigations.

“We start with the material that is available, like photographs or videos,” says Greek architect Christina Varvia, deputy director at Forensic Architecture. “We try to figure out how events match up and evolve in time and space. In one case from Chicago, a police officer shot a black man because he was carrying a gun, for which he had a license. We used footage from CCTV and the officer’s body cam. In a case in a Syrian prison we only had one satellite image and had to base our investigation solely on witness testimony. In Mexico, we had dozens of testimonies about the case of the 43 missing students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College, but they were all over the place. The authorities had covered up the event and destroyed evidence, so we went ahead with data mining. We organized the testimonies and started collecting data. We built a platform and mapped the position of each involved party in time and space. We drew up an 18-meter chart that we put on display in Mexico City, showing the timeline of the event and the actors’ locations. It revealed that the official line was completely different to the testimonies of the students who survived, but similar to the testimonies of drug cartel members who were in custody and spoke under duress. That’s when you know that something is very wrong,” she says.

According to Forensic Architecture’s report, the agency was hired by Fyssas’s family to synchronize the video footage related to the incident, determine the direction of the moving persons and vehicles that appear in the material and the real time of their movements, identify the time of the 36-year-old’s murder and establish if there were any uniformed pedestrian police officers present and, if so, when and where they appear.

Forensic Architecture’s work is a combination of architecture, technology, politics and art. Its studies are indeed often works of art in their own right, held in regard not just by courts, investigative committees and the media, but also by museums and cultural organizations.

The agency was one of the four finalists for the 2018 Turner Prize, the biggest art award in the UK, for its presence in exhibitions at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art, documenta 14 in Kassel, and the contemporary art museums of Barcelona and Mexico City.

The agency’s presence at such events allows it to start a public debate on cases that are considered closed as well as to address specific sociopolitical and aesthetic issues. It creates the conditions for issues to be brought out into the public sphere.

“We choose cases that have political significance, in which the state and the police come under scrutiny,” says Varvia, adding that one of the cases the agency has recently taken on is the death in downtown Athens of LGBTQ activist Zak Kostopoulos last September.

“In particular we are investigating whether his death had anything to do with his identity,” she says, explaining that FA has created an online platform where members of the public can upload audiovisual material related to the case. “There was no material. What we saw from security cameras had been collected at the request of his family. The police had not even collected that,” she says.

They also use biometric data and new forms of surveillance, which, while disputed for infringing on privacy, can prove very useful – as was the case in the Fyssas murder investigation.

“The debate is fierce over new technologies like facial recognition software, for example. Can you teach a program to understand who is a criminal and who is not? What are the characteristics of a person who is labeled a criminal? All of these are very controversial issues,” says Varvia.

To find out more about the agency and its work, visit www.forensic-architecture.org.