Diving into the world of the dead

Iordanis Dimakopoulos talks about the mound that holds the Royal Tombs of Vergina

Iordanis Dimakopoulos is an architect and erstwhile director of restoration of ancient monuments at the Greek Ministry of Culture, where, among others, he worked on the site of the Royal Tombs of Vergina in northern Greece. He is also the author of the book “Kelyfi Prostasias en Eidei Tymvou” (1993), in which he described the situation at the Archaeological Site of Aigai (Vergina) in the fall of 1980: “It was a bizarre jumble of sheets of metal and layers of concrete, beneath which one could – ducking or tripping over wooden beams – catch sight of small sections of the monuments and that only when Andronikos – with his famously affable manner – allowed the screen covering the facade of the royal tomb to be lifted. In fact, he conducted the tour himself, and not just of the tomb, but of the other monuments too.”

The tombs of the Macedon kings – among them that of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great – had been uncovered in the space of three years by archaeologist Manolis Andronikos, who literally razed a 12-meter artificial hill that dated to ancient times. The challenge for the Ministry of Culture was how to protect the monuments yet still make them accessible to the public.

The scene described by Dimakopoulos stays with me as I leave the new and impressive edifice of the new Museum of Aigai – which opened at the end of last year in Vergina, 75 kilometers west of Thessaloniki, and introduces visitors to the Macedonian metropolis – and head into the center of the small village for a dive into the world of the dead. What I see is similar to what Andronikos encountered before he began excavations in 1976: a green hill. It is much smaller than 12 meters today, of course, and has a path leading underground. It’s been years since I last visited the site and I have forgotten how awe-inspiring the Museum of the Royal Tombs can be when you’re enveloped by its darkness.

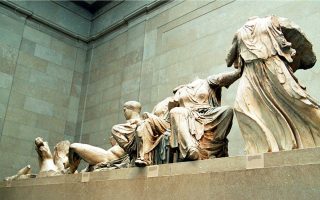

My eyes need time to adjust. I walk a few steps and stop at the funerary steles I see in front of me, before descending deeper still, to reach the entrance to the tomb of Philip II. I see what the archaeologists saw four decades ago: a monumental facade elaborately decorated by the ancient Macedonians in 336 BC with the scene of a hunt of wild animals, the blues and reds still vivid after so many centuries. I notice the king’s golden larnax and wreath, his armor and weapons, and the vessels found inside the tomb. I move on to the Prince’s Tomb and the other monuments contained in the tumulus.

“We wanted to strike a contrast between the outside and the inside. To create the sense of penetrating the belly of the earth, being surrounded by half-darkness, feeling that sense of awe, of passing from the world of the living – from warmth and light to darkness and cold – to the world of the dead,” Dimakopoulos, 83, tells me later, when I meet him at his home in Athens.

‘We wanted to strike a contrast between the outside and the inside. To create the sense of penetrating the belly of the earth, of passing from the world of the living to the world of the dead’

In his home in the western suburb of Aegaleo, a house built by his philologist father who also happened to be Andronikos’ teacher in Thessaloniki, Dimakopoulos describes how he first met the distinguished archaeologist and the meeting that took place in September 1983 in Vergina between the Culture Ministry’s officials and Andronikos to discuss how the Museum of the Royal Tombs would be designed.

“I told them that this was a special case. What we had to do was return the site to its prior state, not in a precise manner – we didn’t know what it looked like originally – but so that it would evoke a sense of what it was. And also to leave the interior open, a single space, so as to create a kind of shell,” he says.

The basic idea, which Andronikos also agreed with, was to build a single shell or many smaller shells that would protect the monuments but were also big enough to allow visitors to enter. These would then be covered with dirt so as to give the sense of a tumulus.

“Thanks to the natural insulation provided by the dirt walls, the conditions surrounding the monuments would be close to those that preserved them over the centuries in the first place,” he explains.

Indeed, the temperature inside the artificial mound never exceeds or drops below 17-18 degrees Celsius, while the lights are special high-pressure sodium lamps that contain UV radiation.

The restorer talks to me about the tombs’ geometric characteristics, the structural integrity of how they were architecturally designed, the similarities he sees with Plato’s teachings in geometry and the challenges of carrying out this complex project. The studies for it began in 1983 but it did not start until 1991. The museum was inaugurated in 1993, a year after Andronikos died.

“The entire structure is reversible, in that it can be dismantled and removed very easily,” says Dimakopoulos. “The walls, the beams and the columns were manufactured at a factory in Thiva and brought to Vergina. No concrete was poured there.”

I cast my mind back to my visit to the site and to the tomb of the “free columns,” as it’s known, the Tomb of Persephone and the Heroon, which is slightly elevated compared to the other monuments. I remember coming back out into the light and turning back for one last glance at the dirt mound, thinking that it looks like a noble gesture, a gift from the ancient Macedonians, who taught us a few more things about life and death.