Rethroning the violin in Epirotic music

American ethnomusicologist Christopher King to hold a special event on the evolution of the northeastern Greek region’s traditional sounds in Athens

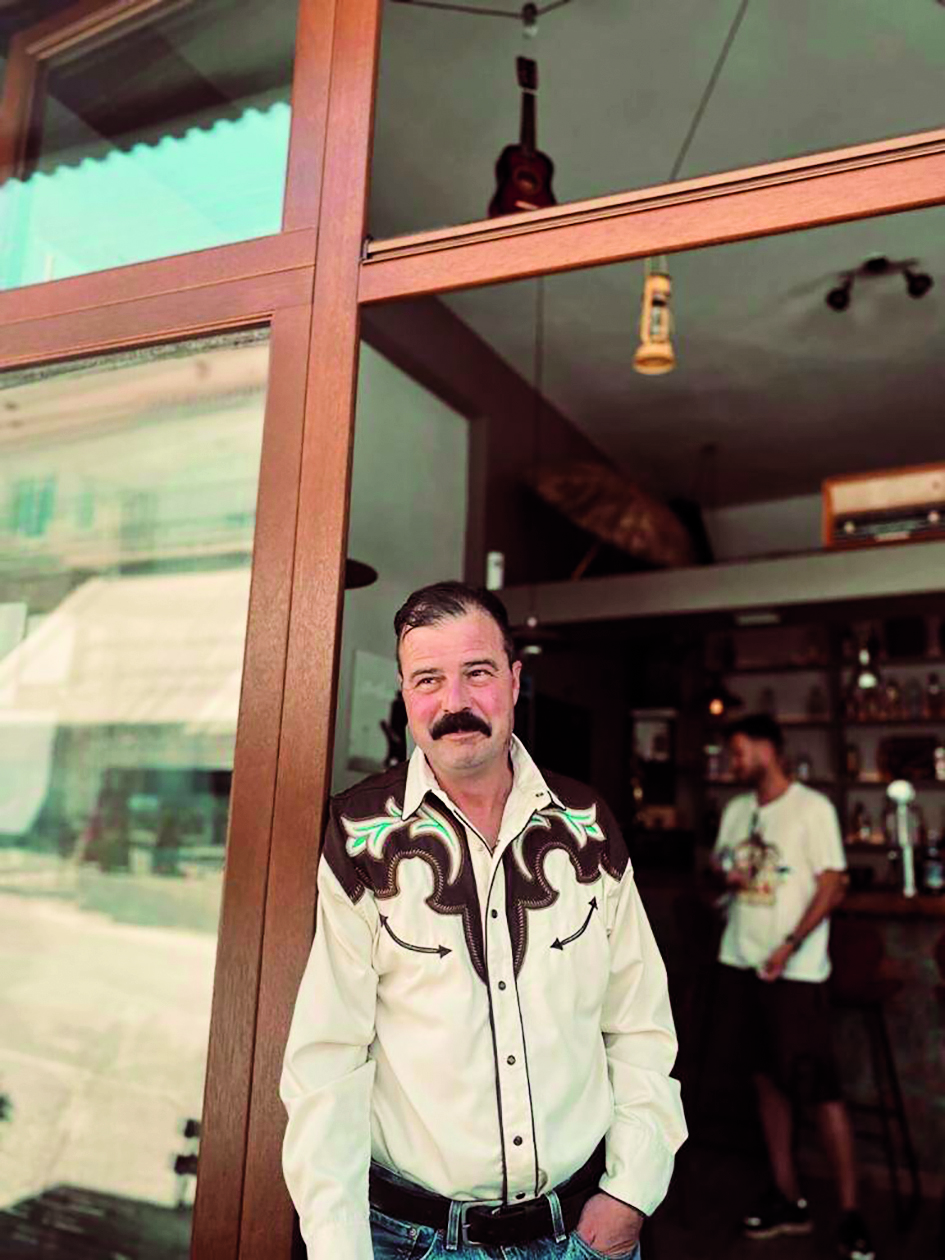

A multicultural lakeside city hosting people of different ethnic backgrounds and their music: “This was Ioannina 200 years ago, a completely different state and society than it was after World War II,” says Christopher King, the distinguished American ethnomusicologist who has made the northwestern Greek region of Epirus, of which Ioannina is the capital, his second home.

“I am certain that cultural exchanges also took place between the different population groups,” King tells Kathimerini a few days before he is expected at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens for a special event challenging the prevalent notion that Epirotic music is all about the clarinet.

At the November 30 event – wittily titled “When Violin Was King” – King will share rare recordings from the early 20th century, when the violin was the key instrument, present the conclusions of his own research into the subject and hold a free-form dialogue with Andreas Zombanakis, the president of the Board of Overseers of the Gennadius Library, while musicians Kostas Karapanos (violin), Aurel Qirjo (violin) and Marios Toubas (laouto) will perform traditional Epirotic music.

At the November 30 event – wittily titled “When Violin Was King” – King will share rare recordings from the early 20th century, when the violin was the key instrument, present the conclusions of his own research into the subject and hold a free-form dialogue with Andreas Zombanakis, the president of the Board of Overseers of the Gennadius Library, while musicians Kostas Karapanos (violin), Aurel Qirjo (violin) and Marios Toubas (laouto) will perform traditional Epirotic music.

King explains that despite the widespread view of the clarinet as the defining sound of traditional Epirotic music, the instrument has only been used by music ensembles in the region for around 80 years. “These were the influences of our parents and grandparents, who conveyed them to us,” says King, noting that while we know so much about Greece’s ancient and Byzantine history, there are serious gaps where the Ottoman occupation is concerned and in the 19th century.

He points to musician Alexis Zoumbas, who immigrated from the village of Grammeno after the First Balkan War in the 1910s to the United States, where he recorded more than 36 songs from his native Epirus. “Of those, only two were played on the clarinet,” notes King, who won a Grammy in 2002 for Best Historical Album.

A few years later, another Epirote musician, Mitsos Halkias, went to Athens and recorded a series of traditional songs on the violin. These recordings, along with old photographs of music ensembles, offer compelling proof that the songs we hear today played on the clarinet were originally played on the violin.

“The violin was introduced to Greece between 1650 and 1700,” says King, who has developed his own theory about how the instrument reached Epirus. “Gypsies living in Romania and who knew the violin immigrated at around that time to northern Greece and Albania. I am convinced that they must have had a very good reason for leaving, given that they were not nomadic, and that reason was music,” says the author of “Lament from Epirus” (2018, W.W. Norton & Company).

“They hoped that their music would bring them respect and more money than other occupations, thus reversing the stigma associated with them,” says King. “I have met musicians in Grammeno of Romani descent who are widely respected by the local community because of their art.”

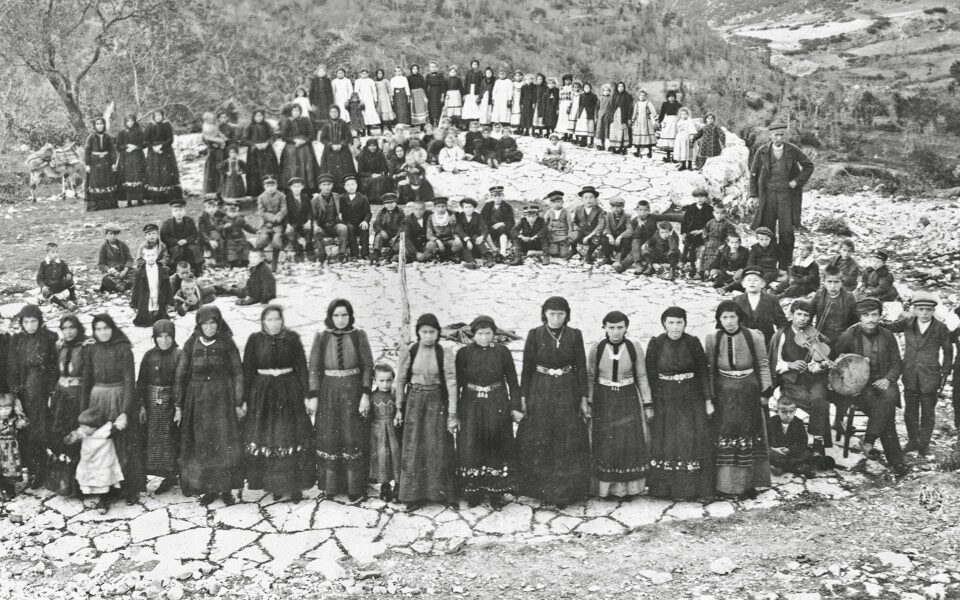

Every village in the area of Zagori had a Roma population at the time, usually living in neighborhoods created just on the outskirts of the main settlement. In Leskovo (today Tria Elata), for example, the Roma are thought to have made up 60% of the population, while Parakalamos and Grammeno also had large Roma communities.

The majority of musicians in those days were of Romani descent. “The melodies they played were a mix. They were influenced by the pentatonic music from Pogoni in Epirus, which was played on a flute but could be easily transcribed to the violin,” he says, adding that Ottoman and Arabic music, especially the dancing music played at court, was also in evidence. “They had further incorporated melodies from Romania and Ukraine, from songs that are still heard there, but also from music of the Romaniote Jews, which, unfortunately, is largely unknown to us.”

The violin was also present in the music of Ukraine’s Ashkenazi Jews – a genre known as Klezmer that survives to this day. “The Ashkenazis of Ukraine were in communication with the Romaniotes of Epirus because of their religion,” says King, noting that well-known songs like “Genofeva” and “Doina” are played the same way in Odesa and Epirus.

“Because of the Holocaust and the near-extermination of Ioannina’s entire Jewish community, we have no information about the ‘social’ music, the music played at their celebrations and weddings,” he says, explaining that there is more information about the music used in religious ceremonies thanks to the Romaniote Jews who immigrated before the Holocaust to New York, where there is still a synagogue established by the descendants of the Ioannina community in downtown Manhattan.

But 110 years ago, a typical Epirotic music band consisted of two or three violins and a tambourine, whereas now it consists of a clarinet, a laouto, a tambourine and an accordion. Before the violin, pride of place was held by the shepherd’s flute, known as a tzamara. The clarinet was brought to Greece in 1830 by traveling Turkish musicians, but it did not dominate Epirotic music until the 1920s.

“It’s an expensive musical instrument compared to the cheaper violin because of its mechanical parts,” observes King, adding that it nevertheless gradually replaced the violin, but not before it was elbowed out by the accordion – which was already familiar in the area – after World War II.

The only instrument that has alway been part of the traditional Epirotic band is the tambourine. “It’s the instrument every Roma musician learns first, so they can practice rhythm,” says King.