For the winner in Turkey, one prize is an economy at the edge of crisis

ISTANBUL – Inflation in Turkey remains stubborn at 44%. Consumers have watched their paychecks buy less and less food as the months tick by. And now, government largesse and efforts to prop up the currency are threatening economic growth and could push the country into recession.

It’s a tough challenge for whoever wins the runoff election for the presidency Sunday. And it’s an especially complicated one if President Recep Tayyip Erdogan remains in power because his policies, including some aimed at securing his reelection, have exacerbated the problems.

“The relatively strong economy of the past several quarters has been the product of unsustainable policies, so there will most likely be a contraction or recession,” said Brad W. Setser, an expert in global trade and finance at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Working Turks will feel poorer when the lira falls in value,” he said of the local currency. “People will find it harder to find a job and harder to get a salary that covers the cost of living.”

Economic turmoil in Turkey, one of the world’s 20 largest economies, could echo internationally because of the country’s broad network of global trade ties. It will also likely dominate the immediate agenda of whichever candidate prevails in the runoff election.

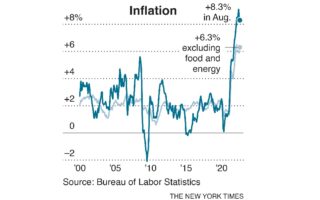

During Erdogan’s first 10 years in power, he oversaw dramatic economic growth that transformed Turkish cities and lifted millions of people out of poverty. But some of those gains have been eroded in recent years. The national currency has lost 80% of its value against the dollar since 2018. And annual inflation, which reached more than 80% at its peak last year, has come down but was still 44% last month, leaving many feeling poorer.

While economic orthodoxy usually calls for raising interest rates to combat inflation, Erdogan has insisted on doing the opposite, repeatedly reducing them, which economists say has exacerbated the problem.

During his reelection campaign, Erdogan showed no intention of changing his policies, doubling down on his belief that low interest rates would help the economy grow by providing cheap credit to increase Turkish manufacturing and exports.

“We will work relentlessly until we make Turkey one of the 10 largest economies in the world,” he said at an election rally this month. “If today there is a reality in Turkey that does not allow its pensioners, workers and civil servants to be crushed under inflation, we succeeded by standing back to back with you.”

In other rallies, he vowed to continue lowering interest rates and to bring down inflation.

“You will see as the interest rates go down, so will inflation” he told supporters in Istanbul in April.

In the run-up to the election, with the cost-of-living crisis on many voters’ minds, Erdogan launched a range of expensive policies aimed at blunting the immediate effects of inflation on voters. He repeatedly raised the minimum wage, increased civil servant salaries and changed regulations to allow millions of Turks to receive early government pensions. All of those commitments must be honored by whomever wins the election, meaning greater government spending into the future.

Exacerbating the economic stress is the vast damage caused by the powerful earthquakes that destroyed large parts of southern Turkey in February. In March, a government assessment put the damage at $103 billion, or about 9% of this year’s gross domestic product.

At the same time, the government has heavily intervened to slow the decline of the Turkish lira, mostly by selling foreign currency reserves. During one week in early May, the reserves declined by $7.6 billion to $60.8 billion, according to central bank data, the largest such decline in more than two decades.

To address that, Erdogan has reached agreements with countries including Qatar, Russia and Saudi Arabia that would help shore up reserves in Turkey’s central bank. Saudi Arabia announced a $5 billion deposit in March, and Russia agreed to delay at least some of Turkey’s payment for natural gas imports until after the election.

The terms of most of these agreements have not been made public, but economists said they were part of a short-term strategy by Erdogan more focused on winning the election than on ensuring the country’s long-term financial health.

Should Erdogan win, as many analysts expect he will, few expect him to dramatically change course.

“I don’t think the current government has a plan to fix this because they don’t admit that these problems are due to policy mistakes,” said Selva Demiralp, a professor of economics at Koc University in Istanbul. “I don’t see a way out for the current government.”

Erdogan came out ahead in the first round of elections May 14 with 49.2% of the vote but fell short of the majority needed to win outright. The main opposition candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, won 45%, and a third candidate, Sinan Ogan, won 5.2%. Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu will compete in the runoff.

Most analysts give Erdogan an edge because of his strong showing in the first round and the likelihood that he will inherit significant votes from Ogan, who formally endorsed Erdogan on Monday. Erdogan’s political party and its allies also maintained their majority in parliament, allowing Erdogan to argue that voters should choose him to avoid a divided government.

If Erdogan sticks to the status quo, economists expect the currency to sink further, the government to impose restrictions on foreign-currency withdrawals and the state to run short of foreign currency to pay its bills.

In its campaign, the political opposition promised to follow more orthodox economic policies, including raising interest rates to bring down inflation and restoring the independence of the central bank, whose policies are widely believed to be overseen by Erdogan himself.

But if he becomes president, Kilicdaroglu will inherit a financial situation that will require immediate attention, economic advisers to opposition parties have said.

In addition to honoring the additional spending added by Erdogan in recent months, a new administration would need to respect his financial arrangements with other countries, the terms of many of which are not clear.

“What are the political terms? What are the financial terms?” said Kerim Rota, who is in charge of economic policy for Gelecek Party, a member of the opposition coalition. “Unfortunately, none of those numbers are reflected in the Turkish statistics.”

If it came to power, the opposition would need both short- and medium-term plans to bolster the government’s finances and restore the confidence of investors, he said. But restricting its ability to maneuver would be the majority in parliament led by Erdogan’s party and its allies.

“We need a very credible medium-term program, but the question is if the majority of the parliament is on the AKP side, how can you manage a five-year program?” he said, using another name for Erdogan’s party.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.