What does the tourist boom mean for Greece?

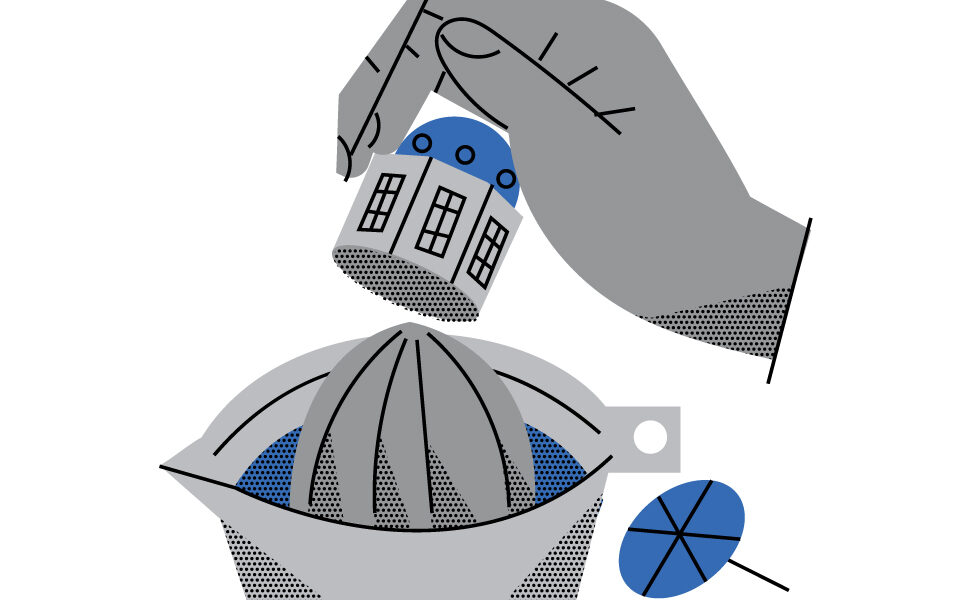

The Belgian city of Bruges, with a population of 20,000 residents, welcomes 8 million visitors every year. Here’s how a resident of the city described the current state of affairs to the Financial Times: “Twice this year alone, tourists have asked me where they could buy tickets to go inside the city center. They see it as a theme park. It’s always been touristic, but the scale is dangerously tipping toward ‘too much.’”

Are European cities becoming theme parks? The seemingly unstoppable rise of tourism is transforming host countries in ways that until recently belonged to the realm of the imagination. Greece is among the places most affected by this trend, as the global demand for it appears to know no limits. Most Greeks are appropriately concerned. A public discussion began two years ago about access to the “Greek summer,” a term describing the many ways in which Greeks and non-Greeks alike have been experiencing the joys of the summer season in Greece. The key question is whether the current tourist boom is something unquestionably positive and desirable for the country and its inhabitants.

Two issues tend to dominate the conversation. The first is overtourism, related to the sustainability of tourism. Is Greece, by attracting more visitors, ultimately “cannibalizing” its product, while also destroying itself in the process? The second points to how tourism limits access to the most desirable locations for locals; are Greeks in the process of being excluded from their own country? What are this year’s trends suggesting?

Tourism in Greece continued its upward trajectory, surpassing both 2022 and the record pre-pandemic 2019. Data from the Bank of Greece show that travel receipts between January and September 2023 period have reached 18 billion euros, compared to 15.6 billion euros for the same period last year and 16.1 billion euros for the same period in 2019. Air passenger data confirms that 2023 will be the best year for Greek tourism, besting the 31 million arrivals from 2019. In turn, these numbers underscore five key trends.

The first one is that tourism in Greece (but, also, globally) has so far proven particularly resilient to external shocks like climate change, regional geopolitical instability and inflation. In other words, demand for the “Greek summer” seems to be so great that it is offsetting the effects of negative developments. Clearly, this trend is driven by deeper, structural causes rather than being a conjectural, post-pandemic reaction.

Secondly, overtourism does not seem to produce, not yet at least, a decline in the most popular destinations. Places that initially appeared to be losing ground, such as Mykonos and Santorini, did regain their momentum following the end of August. Demand for, say, Santorini seems to outweigh the drawbacks of a poor experience caused by overcrowding. Some tourists may turn away from this island, but they are immediately replaced by many other willing visitors. The solutions proposed to tackle the problem of overcrowding, like the implementation of a national “destination management” strategy, seem rather unrealistic for a country like Greece. Investments in infrastructure might perversely worsen the problem by attracting even bigger crowds. So, while there is room for more people, the real question is at what cost.

Paros is now the new Mykonos, Sifnos the new Paros, Amorgos the new Sifnos, and so on. Places that were unspoiled until very recently are now being pushed into this meat grinder

Thirdly, the spread of tourist arrivals beyond the summer season is gradually turning into a reality, one likely to be further encouraged by climate change. Greek air passenger data show increased tourist flows in October and November, a phenomenon clearly visible in Athens, where an ever-rising number of hotels and Airbnb venues exhibit unprecedented occupancy rates, including during the winter months. Extending the tourist season has been a long-standing goal for the Greek tourist industry; however, this does not necessarily mean that the same numbers of visitors will be spread over more months; rather, it means that the numbers will increase even further. Fourth, this rise is driven primarily by the traditional tourist markets of Western Europe and North America; indeed, all this growth is taking place while the Chinese are still hunkering down at home. The coming tsunami from new, vast Asian markets has yet to begin, although all the signs are there; once this gets going, the numbers will explode.

Finally, tourism is boosting real estate development, as the demand for views, land, and vacation homes is becoming explosive. On top of it, this demand is taking place in a legal context characterized by very lax enforcement of land zoning rules. Essentially, this demand is transforming several of the most beautiful islands of the Aegean and Ionian seas, along with their formerly vibrant communities, into (primarily foreign) investment-driven suburban developments, dressed with a fake vernacular style. Santorini is leading the way, showing us what the future holds in store: A once beautiful volcanic island with a vibrant local culture, it has now effectively turned into a garish, overbuilt theme park for Instagram-obsessed sunset seekers. And the process is accelerating: Paros is now the new Mykonos, Sifnos the new Paros, Amorgos the new Sifnos, and so on. Places that were unspoiled until very recently are now being pushed into this meat grinder.

In short, tourist growth has been consistently upward trending over the last 60 years. This suggests that the rise of tourism is unlikely to abate; instead it will probably intensify over the course of the next decade. As a result, tourism-related income will also rise, which is what Greece mostly cares about now. At the same time, however, a rising proportion of this income will accrue to foreign investors, with the domestic side having to satisfy a rising demand for, mainly imported, low-skilled labor.

Tourism will shape the texture of daily lives in Greece in ways that are difficult to fathom today. It is easy to predict, though, that the Greek summer will fade into the sunset for most Greeks who will be unable to afford it. Despite growing citizen activism calling for free access to the sea, the pressure for commercial exploitation is such that it is likely to overwhelm it. Hence the need to shift away from merely worrying about what is happening now and toward generating innovative ideas about how to manage tourism. One thing is clear, though: If we fail to tame tourism, it will control us and the future will be all the bleaker for it.

Stathis Kalyvas is the chairman of the Board of Directors at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC) and Gladstone Professor of Government at the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations.