‘I had to find the strength to carry on’

Greek NFL champ George Karlaftis talks about the impact of losing his father at age 13, moving to the US and the climb to the top in football

The world of sports has often provided us with beautiful fairytale-like biographical accounts. And some of these incredible journeys started in Greece, as though following in the footsteps of Hans Christian Andersen, who traveled to the country in 1841 and wrote about the impressions its colors and landscapes had made on him.

Some of the famous Danish storyteller’s greatest heroes were people with special gifts like kindness, talent and generosity. One such young man is George Karlaftis, the 21-year-old US National Football League (NFL) champion defensive end of the Kansas City Chiefs. Formerly a water polo player for Athens club Panathinaikos and the national youth team, Karlaftis talks to Kathimerini about his early years in Greece and his rise to stardom in the world of American football.

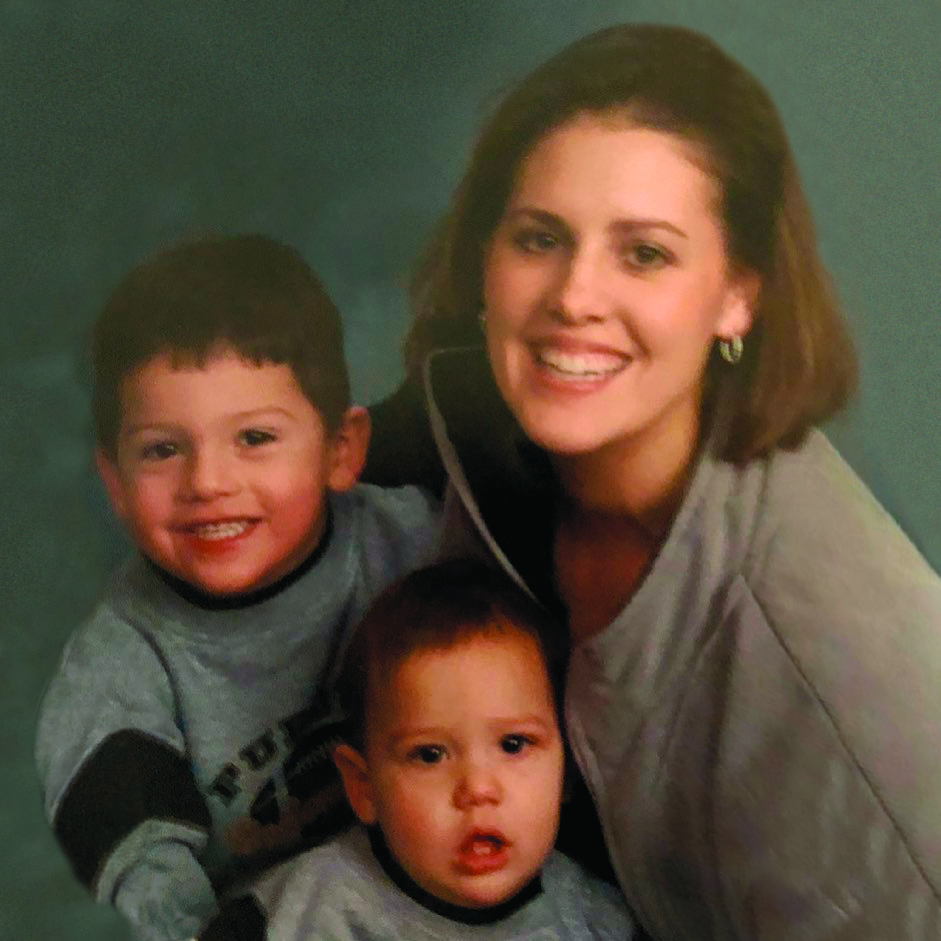

Karlaftis was born in Athens on April 3, 2001, and grew up in the leafy northern suburb of Psychiko until he was 13. That was in 2014, the year when he lost his father Matthaios, who died of a heart attack at the age of 44. “When I was given the bad news by my mother, my uncle and a close friend of his – they were together when they told me – I burst into tears. I couldn’t believe it. After two or three hours, though, something inside me told me that I would have to find the strength to carry on for my family. I knew that I had to be there for my siblings, and especially for my mother,” says Karlaftis, referring to two brothers and sister, and his American mother, Amy.

Despite his young age, he felt that it was important to push his own feelings aside. How could a child do such a thing? “I remember being in the pool during polo practice and suddenly breaking into sobs, for no reason. It was a very difficult moment. It was a moment that lasted months and years.”

What gave him the strength to stand by his family, beyond a sense of duty? Two very important people in his life, he says. “My grandfather Giorgos, really, and my uncle, Aristidis. I have learned everything I know from them and from my father and mother, and I have relied on them throughout. I knew that I had to be there for my brothers, my sister and my mother, for anything they needed,” he stresses.

Throughout our conversation in Athens, his grandfather sits in an armchair across from us, in a relaxed yet attentive pose, with his head resting on the three fingers of his right hand. He cuts a dignified figure, discreet and courteous, as he listens, thinks and observes, as though keeping check (in the best possible way) on the quality of the discussion.

“My mother is from the United States and that’s where her family is. We thought it best after losing my father to move there because life was easier and offered more opportunities. I live in Kansas now and my mother and siblings are in Indiana,” says Karlaftis.

“I grew up in a family where love was the most important thing. It was Number One. That’s what I was taught by my grandfather and grandmother: love, truth, faith, respect for the members of my family and for others. That is everything,” he adds.

Karlaftis’ fate appeared to be written in the stars, as sports was a very big part of growing up and a chief interest and activity for his entire family. “My mother did sports, though not at a very advanced level. Both sides of the family are athletic. For my mother, it was basketball, swimming, volleyball, all sorts. My father did track-and-field and played a bit of football too. I knew I wanted to do something sports-related from a very young age. There were times when I wanted to be a soccer player, then a basketball player, then a water polo player, but I ended up in American football,” he says.

‘That’s what I was taught by my grandfather and grandmother: love, truth, faith, respect for the members of my family and for others’

Karlaftis’ father sustained a serious head injury playing football at the University of Miami in Florida that forced him to give up sports. He completed his degree and got a PhD in civil engineering from Indiana’s Purdue University – where he met Amy – before going on to work as an associate professor at the National Technical University of Athens, producing important research. He was given tenure on the day of his death. There is now a Young Researcher Award named after him.

‘C’est la vie’

George began taking an active interest in football about a year into his stay in the US. It was a big change from water polo.

“There’s a French expression: C’est la vie – that’s life. A lot of different things happened; my plans changed, my life, my environment and my friends,” he says.

Explaining why he thinks the sport has never taken off in Europe, he says: “I think it’s like soccer, which has had the same kind of lukewarm reception in the US. Football is a very different sport, one that is, I would say, quite barbaric and quite hard to understand. Maybe that’s why it isn’t played so much outside the US. A few efforts are under way in the UK and in Germany, and I understand that they’re doing well, but it’s a tough game and a very expensive one too. The gear alone is very expensive. The helmet, uniform, shoes – they cost at least $1,000. It’s also hard to grasp in terms of the rules, theories etc, but also because it plays out very fast on the field,” explains Karlaftis.

What with one thing and another, his coach, Andy Reid, and other Americans have started calling him “Greek Freak,” a nickname that began with the Greek-Nigerian basketball star Giannis Antetokounmpo. Karlaftis appears to find the moniker amusing; not so his grandfather, who believes Giannis has the “copyright.”

“It’s a real honor to be called that, given everything that Giannis Antetokounmpo has done, not just for himself and his family, but for Greece too. Being compared to Giannis is a real honor. I haven’t spoken with him yet. I’d really love to, both as a fan and athlete to athlete. I guess it hasn’t really sunk in yet, because I grew up watching him and saying, ‘I want to be like him,’ and now here I am, a pro athlete. It’s a lot to take in,” he says.

It’s in the genes

Football is a high-impact sport that can take a heavy toll on the body. What kind of physical, mental and technical preparation goes into reaching this level?

“Good genes, first of all, which I inherited from my grandfather and my parents. My height is good at 1.94-1.95 meters, and I have speed – not to boast or anything. I realized that I had good athletic qualities from a very young age, but school was always my top priority. I also knew that if I wanted to succeed, I had to work very hard. That’s something my family instilled in me. And that’s what I did. From knowing nothing about football, I reached the top with my team. That’s what comes from a lot of hard work, love, sacrifice and principles. The principles you’re instilled with, whether positive or negative, stay with you for the course.”

Karlaftis is now enjoying the fruits of his labor and an enormous amount of fame and popularity, especially after his team won the Super Bowl earlier this year. His mind is not on fame, though.

“I’m happy about it and will be for the rest of my life. It’s an incredible achievement that gives me a lot of joy and satisfaction, but I already need to start focusing on next season. There’s a lot that needs to be done, with the team and personally so that I can become a better player and better help my team,” he says.

Successful athletes are also often seen as role models by youngsters and can be a strong presence in their lives. Does he find the idea of representing a certain way of life, certain principles and values, too much to bear? “No. What I want to tell all kids, and those in Greece especially, but also in the US, who see me and say, ‘I want to be like him,’ is to follow their dreams. I have had some pretty crazy dreams in my life, ever since I was a kid. And I’d also like to urge parents to encourage their children. I always had the support of my family. If there is one message I want to send to children, it’s always follow your dreams and believe in yourself.”

Roots and opportunities

Greece has not been Karlaftis’ base for some years now, though he makes a point of staying close to the people that attach him to the country. “My cousins, my aunt and uncle, and my grandfather are here. I come twice a year or as much as my schedule allows and I know I always have my family. I have friends, a small house on Paros that I adore and visit every summer, and, of course, I have my grandfather whom I speak with every day. Greece is always with me. Even the helmet I wore at the Super Bowl had the Greek flag on the back,” he says.

So what, briefly, do Greece and the US mean to him?

“That a tough question,” he says, pausing to think. “I’d say, fatherland. Yes. It says it all. And the US? I’d say opportunities, lots of opportunities.”

For Karlaftis, the US is indeed the land of opportunity; and one of the country’s most important attributes, he says, is that it is well organized. “If there was some way to give children in Greece opportunities, especially in education, that would be ideal. Opportunities and organization.”

Panathinaikos

Green is Karlaftis’s favorite color; no surprise since he’s a die-hard Panathinaikos fan – the Athens team whose symbol is a clover leaf.

“I’ve been Panathinaikos since I was a kid, a baby,” he says and smiles as he shows me a photograph of him as a 2-day-old infant in his uncle’s arms, dressed in a onesie emblazoned with the team’s logo. “I was born Panathinaikos. My father, my grandfather, my brothers, my cousin Giorgos, all Panathinaikos. The other half of the family is, of course, Olympiakos,” he says laughing, referring to his team’s archrival.

“I followed the team in soccer and basketball and later played water polo for them. Playing polo for Panathinaikos and for the national team was like a dream come true,” he says.

His grandfather Giorgos has something to add before we say goodbye, giving us the perfect epilogue to our conversation: “When my grandson went to Kansas, people from the team asked me, ‘What can George do for us?’ I answered, ‘I don’t know what he can do for football, but I do know that he’s a very good young man.’”