Greece’s allies in fight for Parthenon Marbles

Going behind the scenes of the talks that led to UNESCO’s 2021 turnaround and the return of the Fagan fragment to Athens from Sicily

“We learn to pick our fights in multilateral diplomacy, and [the return of the Parthenon Sculptures] was worth fighting for,” sums up one of Greece’s unexpected allies. Egyptian diplomat Maged Mosleh is speaking for the first time about the battle fought – and won – by Greece at the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee’s session in Paris in 2021. He was the chair of the meeting at the time and played a vital role in the unanimous support – for the first time in 40 years – of a landmark decision that was exclusively designed to pave the way for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece.

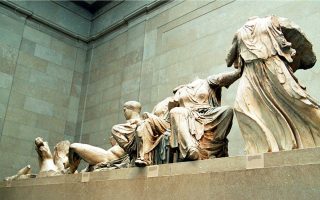

The Greek side had painstakingly prepared for the meeting, even planning how to connect with Paris via video conference. Acropolis Museum Director Nikolaos Stampolidis has chosen to make his stand from its second-floor balcony, setting up the camera so that it would show the room of exhibits, full of people, in the same frame as himself and the other speakers (Giorgos Didaskalou and Vassiliki Papageorgiou from the Ministry of Culture, and Artemis Papathanassiou from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Indeed, when the link to Paris went live, Mosleh spoke with enthusiasm about the museum, which he had visited the past: “I think we would all like to be there today,” he said.

Shift in mood

It was evident well before the matter of the sculptures even came up that the mood had changed. When Zambia’s claim from the Natural History Museum in London came up, the British side merely read a statement outlining its position, among which was a reference to the scientific value of a skull the Africa country wants returned. Mosleh immediately intervened: “I’m quite embarrassed here to say what I’m going to tell you. Just to understand the position of the UK – which you read so brilliantly, in this strong British accent – how is this scientific importance of any relevance to the return an illegally acquired object?” “You have the floor, please explain,” he insisted when the British representative balked. She went on to basically read the same statement again, to which Mosleh responded that the session was interested in hearing the position of the government and not of the museum’s board. He also commented that British museums should learn from the example of Cambridge University, which returned looted Benin treasures to Nigeria.

The Greeks took the floor on Day 2 of the session, as did the British, presenting their position on the matter of the Parthenon Sculptures. But then, the representatives of every other country spoke of their reasons for supporting Greece. “We have been dealing with this case since 1984 and have issued 16 recommendations calling for productive dialogue, yet nothing is happening. We want concrete steps and this committee has the discretionary power to help us in resolving the issue,” Papathanassiou told the committee’s chair. “What I heard is five, six, seven, eight countries supporting your cause. Put in a draft decision and the committee will decide,” Mosleh responded.

The text

Acropolis Museum Director Nikolaos Stampolidis has chosen to make his stand from its second-floor balcony, setting up the camera so that it would show the room of exhibits, full of people

The following morning, the delegation representing Zambia submitted Document 22.17. “When I read it, it was quite obvious that something was cooking behind the scenes,” Mosleh recalls. Zambia was demanding what Greece would never be able to include in the text it had already submitted concerning the sculptures, and which also needed to be approved by the UK.

That was the last meeting of the session though, and all recommendations and decisions had to be finalized and voted on. The clock was ticking and Mosleh was determined to present Zambia’s proposal, so he started reading the document whereby UNESCO strongly urged the United Kingdom to enter into talks with Greece, recognizing that the issue was a bilateral one, as opposed to the UK argument that it was a British Museum matter. “Are there any objections?” he asked. Greece, but also Canada – a UK ally – asked to take the floor. “I have no objection, but I would like to thank Zambia…” Papathanassiou started saying, before Mosleh cut her off: “The interpreters have to leave in a few minutes. If you want to adopt the decision, get to the point.”

The Greek delegate immediately switched off her microphone, giving the floor to the Canadian representative. “I must admit, I’m a little confused. That decision is specific to the Parthenon Marbles whereas we already adopted the recommendation that was agreed upon by Greece and the UK,” she said.

Mosleh responded without a second thought.

“I don’t understand why you are confused. That request for the return goes back to 1984, so Zambia found that we need stronger wording for a specific and separate resolution, a separate decision on the matter to speed it up. This was the logic behind the Zambian draft decision. Yesterday we came to an agreement that there would be an additional decision on the matter. Any objection?” he asked, again. No one raised their hand and the decision was adopted unanimously.

An important win

The decision was “adequately celebrated,” Mosleh recalls, and not just by the permanent Greek representation, “whose head had worked quietly and effectively at the diplomatic level, and by Zambia, but also by smaller countries which felt that the decision was also a victory for them.”

The following morning, of course, he received a visit from the disgruntled Canadian envoy. Kathimerini understands that British diplomats also conveyed the government’s strong dissatisfaction in Paris but also in Athens.

Mosleh was – and remains – adamant that everything was done by the book. In May 2022, after all, the decision was ratified without any objections. The British now have two years to abide by the decision. If they fail to do so, they will find themselves even more isolated at the world’s top cultural organization. Most importantly, though, the decision was instrumental in causing a complete shift in the climate. “It is a weapon in [Greece’s] pocket,” says Mosleh. “You have the decision; now you have to build on that.”

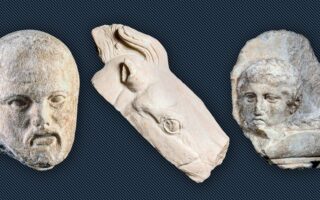

Artemis’ journey from Sicily to Athens

Alberto Samonà knew all about the so-called Fagan fragment, held at the Antonino Salinas Museum in Palermo, when he was appointed councilor of cultural heritage for the region of Sicily in 2020. The fragment had been hosted by the Acropolis Museum in 2008, but any discussion about its proper return had ended in a stalemate, due to lack of political commitment. Samonà, however, was determined to make it happen.

He visited the museum, where its director, Caterina Greco, spoke to him at length about the fragment from the eastern frieze of the Parthenon, which depicts a part of the foot of the goddess Artemis as she looks at the procession of the Panathenaia festival. Over their years of working together, Greco had formed a close relationship with her counterpart at the Acropolis Museum, Nikolaos Stampolidis, and they had debated all sorts of different scenarios about how the fragment had ended up in the hands of Robert Fagan, a former British consul for Sicily and Malta. She told Samonà that the most likely scenario was that it had been given to Fagan by Lord Elgin during a brief stop on Palermo. “This means that if it is finally returned, it will be the first piece of the sculptures looted by Elgin,” Samonà exclaimed. The Greek side didn’t know it yet, but it had two important allies in its bid for the sculptures’ return.

An important conversation which would either signal the green light or put the brakes on the idea had to take place, however, before any move could be made. Samonà met with the then president of Sicily, Sebastiano “Nello” Musumeci, for a long conversation on the issue. “He was very skeptical to begin with, concerned about the potential political repercussions. ‘How would people take it? Would the opposition take advantage of it?’” remembers Samonà. The regional official assured the president that the Sicilian people were mature and just, and would understand. “Go ahead,” said Musumeci.

Samonà had the OK to reach out to Stampolidis and a month later held talks with Greek Culture Minister Lina Mendoni, conveying the desire for the fragment’s return. Many more meeting followed with the Greek side, but also with the government in Rome.

“It was not a simple thing for the fragment to be erased from the state records and be passed to Greece. The Italian law for the protection of cultural heritage raised all sorts of restrictions and bureaucratic hurdles,” Samonà explains. He was also very aware that the move would have to be couched in very diplomatic terms. “There could be no thorny words,” he says.

It was Stampolidis who recommended that the fragment be brought to Greece as a “deposit.” Greece, they had agreed, would – not in return, but as a token of its gratitude – lend two other ancient pieces that would be put on display in Sicily for four years each.

The good news

Samonà called the Greek Culture Ministry to convey the good news as 2021 drew to a close: He had received the first OK from Rome for a long-term deposit (4+4 years), with the prospect of a permanent return of the sculpture fragment to Athens. Some on the Greek side were, nevertheless, skeptical and demanded that the matter of a permanent return be settled before any announcements were made. Even though he could not be certain of the outcome, Samona was optimistic; but he was also adamant that Greece had to accept the deal as it was. “I told them clearly, ‘If we wait, the whole effort might come to nothing,’” he recalls.

The fragment was eventually flown to Greece in the first week of 2022, with Samonà and Greco following a few days later. Samonà remembers feeling incredibly moved when Stampolidis showed them around the Acropolis Museum and stopped in front of the display case where it has been temporarily placed. “It was not an easy path, but it was the right one. I love Greece, also because of my own heritage. My ancestors came from Asia Minor, so I grew up hearing your history and how it shaped my country,” he says.

Even though the opposition in Greece accused the government of undermining the country’s position on the issue of repatriations by accepting the “deposit” for eight years, the reactions in Italy were only positive. Last February, Mendoni and Stampolidis traveled to Palermo to deliver a statue of Athena, as agreed. There, the Italian hosts were warmly applauded during a dinner for returning the fragment to Greece. This positive reception, says Samonà, was one of the reasons why the Italian government then gave the green light for a permanent return. The deal was sealed in June and the fragment was taken out of the case and put back in its proper place in the eastern frieze of the Parthenon at the Acropolis Museum.

Samonà is incredibly proud of his country for what was a historic decision. “What we accomplished shows that there is a way to return the Parthenon Sculptures. Everything we have read since about the return of other fragments from the Vatican, but also the discussion about the pieces at the British Museum, would all have been that much harder, if not impossible, without ‘operation Fagan,’” he says.