An ancient race with contemporary relevance

When Barney Spender ran the Athens Marathon in 2002, he probably did not envisage that running in Greece and tracing the legendary steps of ancient messenger Pheidippides would take up more than two years of his life in the future.

However, Spender and his multi-talented team of collaborators have finished a years-long project to make a documentary about the Spartathlon, the 246-kilometer race run since 1983 in honor of Pheidippides’ greatest achievement – running from Athens to Sparta in 490 BC to seek help in the fight against the Persians.

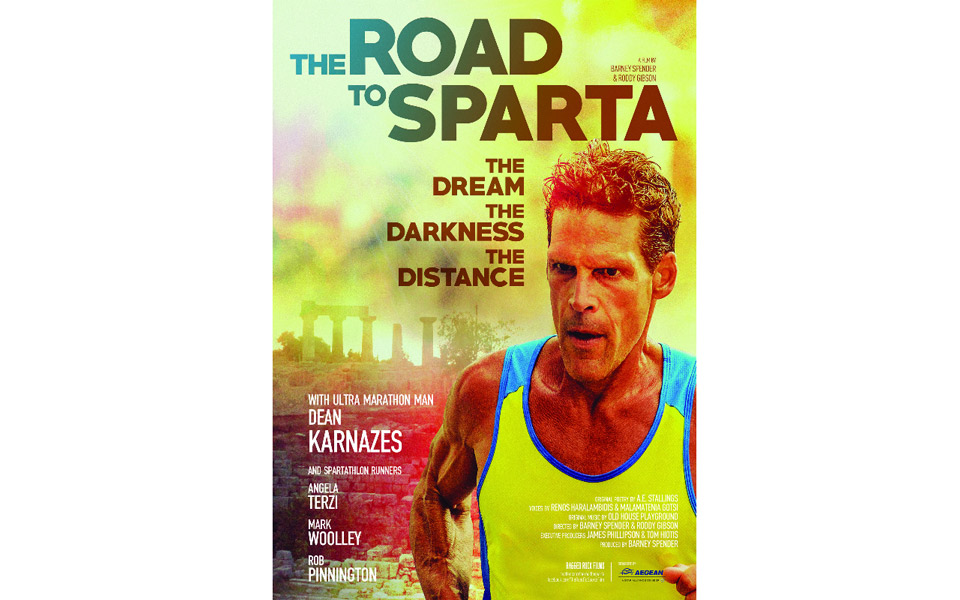

“The Road to Sparta” premiered in Athens last October and was short-listed for the 2017 British Sports Journalism Awards in the UK, finishing “Highly Commended.”

It is described as a love letter to the race and the astounding dedication of those that run it. Perhaps, though, there is more to it than that. After all, themes such as the long road ahead, endurance and exhaustion are all very relevant in Greece at the moment. Spender, who spent several years living and working in Greece just before the crisis broke out, spoke to Kathimerini English Edition about making the documentary and the unique qualities of the Spartathlon and those who run it.

What made you want to make a documentary about the Spartathlon?

Seeing it. And covering it as a journalist. When I lived in Athens (2004-09) I got to see it at close range and I fell in love with the madness of the event. I couldn’t believe that these people would run 246 kilometers. And of course it was linked to the Battle of Marathon, which suited my inner history junkie. When I moved to France in 2009 I came back to do a radio feature for RFI and just thought even that wasn’t enough. It has to be seen to be believed, this crazy odyssey across Greece. It has so many elements to it. Only a film could really get into the heart of it.

Was the attraction to discover what motivates people to run this grueling race or something else?

At the start, for sure. I had interviewed Scott Jurek, who won the race three times, and the British runner Emily Gelder and was fascinated by their single-mindedness, this ability to close off the pain and just run and run and run. I was fascinated by the inner strength that enabled them to carry on. In the film I ask Rob, one of our runners, about the problem of blisters and he said it wasn’t a problem: “Blisters are our friends,” he said. “They keep you awake at night.” That is nuts. I bloody hate blisters.

Did your personal experience from running the marathon in Athens, and elsewhere, give you a better insight into the way the Spartathlon runners tick?

To an extent. In some ways it prompted my curiosity on a couple of levels. When I was training to run marathons which are a mere 42 km, I found I could keep going until I got bored, which was around the three-hour mark. As I have never been very fast this meant the last 10 to 12 kilometers was a real slog. So when I heard about Spartathlon and runners clocking six marathons back to back, I was fascinated. How the hell do you do it? I think where it also helped was that the runners themselves accepted me as another runner. And I could see when I could and couldn’t shove a microphone up their nose. I loved the Athens Classic Marathon, by the way. I ran it in 2002. I clocked about 4:40, which isn’t exactly world-record pace but I remember almost every step of the way. I spent large chunks of it singing “Men of Harlech,” which may have alarmed a few of the other runners. Coming into the Kalimarmaro and slowly taking that final stretch to the line was easily the peak of my own sporting achievement.

The other thing about running Athens in 2002 was Pheidippides, I was full of the story about Marathon and him dropping dead in Athens etc. I hadn’t read Herodotus at that point and so didn’t know the true story. So when I did discover the Sparta run… well, the Pheidippides goalposts moved. I knew I wasn’t going to run it but I wanted to do the next best thing.

Your documentary follows several runners in some detail. By the end of the process, did you find something that connected them, especially given that some did not manage to finish the race?

Very much so. They all came into running via different paths and use running for different reasons. Rob started because he wanted to lose weight, Angie started running alongside her dad’s bike and just built up from a 5k, Dean was a successful corporate executive until he had a meltdown on his 30th birthday and discovered he could run a long distance and still feel good. Mark just says he lives for challenges like Spartathlon. They all have an incredible focus.

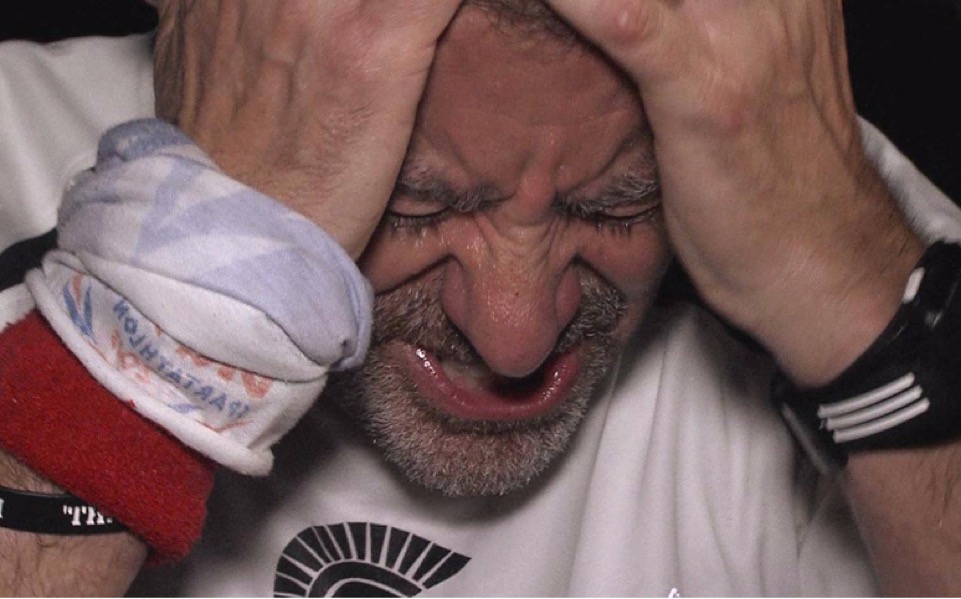

All four of them were outstanding with us on the shoot. Very trusting and very open to the warts-and-all treatment. From a dramatic point of view I didn’t really want all four to finish but on a personal level we were rooting for all of them. When they were going well it was great, when they were hurting it wasn’t pleasant. The temptation is to back off and be a supporter but we still had to get into their faces and show those bad moments. And that goes on beyond the shoot. It is there in the edit room as well as when you look back at the footage. There is something very raw about a person who looks you square in the eye and says, “I failed.” You have to be truthful and sensitive at the same time.

Do you feel that the runners are unsung heroes, given what they have to go through and the fact that the event attracts relatively little attention, compared to the Athens Marathon for instance?

Yes, they are unsung heroes but I am not sure they particularly want to be sung. I get the impression that they like the elite nature of the event. Only 350 runners get to take part each year – that’s all the hotel beds there are in Sparta. It is like being one of Leonidas’ 300. At the start, there is a camaraderie akin to soldiers going over the top. The runners know that only about a third of them will complete the race. You half expect a few strains of “Lili Marlene.” There is no cash prize for the Spartathlon winner, it is purely glory. That is very unfashionable in today’s sporting world where success is largely counted in financial terms. But these men and women just want the glory. Most of the credit for that has to go to the Spartathlon committee. The organization and ethos is fantastic. It is easily the best organized sports event I have attended anywhere in Greece. And, again, perhaps that has something to do with money. The race organizers are all volunteers, not a government-sponsored apparatchik in sight.

I have to say, though, that I am delighted that the Athens Marathon is finally a proper city marathon. When I ran it in 2002 I think there was a total of about 3,000 runners, maybe fewer. It deserves to be a big event. It is great for Marathon and Athens and it is a fantastic course.

Between the symbolic start at the Acropolis and touching the foot of Leonidas’ statue in Sparta, there are a lot of unglamorous moments for the participants, such as running along busy roads with trucks hurtling past. Does that just add to the grittiness or should there be more of an effort to make the Spartathlon special?

The Spartathlon is already special. It is one of the great races in the world. But people can be shocked by the paradox of modern Greece. Dean Karnazes was certainly taken aback. That first stretch past Elefsina isn’t so lovely and Dean was not exactly enamored about the cancerous fumes and dead dogs. And yet you then get this amazing tranquility of Arcadia and the runners climb Mount Parthenio with just the cicadas for company. And that is what makes it special. The run is what it is. This is modern Greece, not ancient Greece. It isn’t a Disney run. And it is certainly no harder than it was 2,500 years ago when Pheidippides did it. He was on his own, carrying his food, wary perhaps of bandits, knowing that if he slipped and fell and twisted his ankle, then his wife, family and friends back in Athens were screwed. He had real pressure on his shoulders.

In terms of putting the documentary together, what were the main challenges you faced?

Ha! Money. Obviously. We raised finance through crowdfunding and I found two fantastic backers, Tom Hiotis and James Phillipson. Aegean Airlines helped us out with some flights but we didn’t have the budget for any fancy-pants stuff. We basically had two cameras following four runners. That meant a lot of back and forth on the road as we hunted down our guys. And we had no backup crew so just as the runners went 36 hours with no sleep, so did we. It was our own Spartathlon. In terms of the narrative, the most difficult thing was working out how to work in the story of Pheidippides. Roddy and I considered and rejected quite a few ideas. And then, when I was out for a run, I had the idea to bring in the genius of A.E. Stallings. She is an American living in Athens, well-versed in Herodotus and simply a great poet. If you are a betting man, put a few quid on her to win a Nobel Prize for Literature within the next 20 years. Alicia loved the idea and produced six new sonnets for the film and with the music that has given it a lovely lyrical mood.

Of course the music also helps. When I was working at Athens International Radio we had a band in called Old House Playground. I loved their music and they were good guys. When I decided to go ahead with the film Tryfon (Lazos) was the first person I called. Even before Roddy, my co-director. I knew I wanted them for the soundtrack and I knew I wanted them on the shoot. That was slightly surreal to be driving around the Peloponnese in the dead of night and hearing a guitar and djemba quietly laying down the beginnings of the soundtrack in the back of the van. OHP’s music on this film is a story in itself.

Geography was also a problem. I am based in Paris, while Roddy, who was also the editor, is in London. That meant monthly trips across the Channel for editing sessions. These depended on our full-time jobs, our families and so on. So it took longer than we would have liked but that actually had a positive effect as we were able to dig deep into the characters. We treated them rather like you would treat characters in a feature film and that meant long conversations about what we cut and what we left in.

Was there anything that surprised you?

Yes, although I feel bad about saying that I was surprised by this because it should be normal: Basically everyone has worked on trust on this film. Everyone is working in deferred payment and has been happy and willing to do so. Perhaps that is a knock-on from the race itself. They have been doing it for the glory rather than the winner’s check.

I have been taken aback by the confidence that people have placed in my mad idea. There were a few raised eyebrows when I announced my intention to make the film on such a meager budget. But everyone who has contributed has made it possible. Tryfon said yes immediately, Clive Martin the music producer could barely contain his excitement, the runners were all quick to agree to it, Alicia bought into it, Bea who did the maps and graphics… I had never met her, Roddy had met her once… it took one meeting and she was on board. It has been such a team effort and that makes me very proud.

You premiered the film in Athens a few months ago and it may get an airing in Thessaloniki as well. What has the reception in Greece been like?

Yes, we premiered at the Athens Adventure Film Festival and the reception was terrific. We had a good audience. Angie and Rob were both there, which made it rather special, and a number of people from the Spartathlon organization. Alicia too. Everyone loved it. I was slightly nervous about how the two runners would react because they hadn’t seen themselves stripped raw like this. They both were in tears and said we had got the atmosphere exactly right about how the race feels for the runner. That was very pleasing.

Thus far it has been very warmly received. We were thrilled to be short-listed at the Sports Journalists’ Association Awards in Britain. It was BBC, ITV, Sky Sports and us. So that was nice. We are now heading into a run of festivals and screenings, starting with the Doc Market in Thessaloniki, and hopefully that means we will be able to sell it to some networks. The DVDs and the soundtrack should both be available for Christmas – and lovely little stocking fillers they will make.

The film starts and ends with scenes from modern-day Athens – riot police, protests, the flea market. Is there any message or inspiration that today’s Greece can draw from the story of the Spartathlon?

We thought it was important to ground the film in modern Athens although I don’t want anyone to think we are equating the riot police with the Persians of 490 BC. It is more like austerity is the modern Darius. We wanted to draw parallels between the ancient and the modern without saying it is the same thing. The threats are different but they are equally real to the citizens of this great city. Perhaps the only conclusion we can draw is that the threat we see now is nothing new for Athens. The Persians, the Romans, the Ottomans, the Nazis, the Colonels and now austerity have all done their worst. Each time the Greeks have found the strength to fight back. It is a long difficult road and the blisters are hurting, but the Greeks will do it. That is not in doubt.