Taming the beast of artificial intelligence

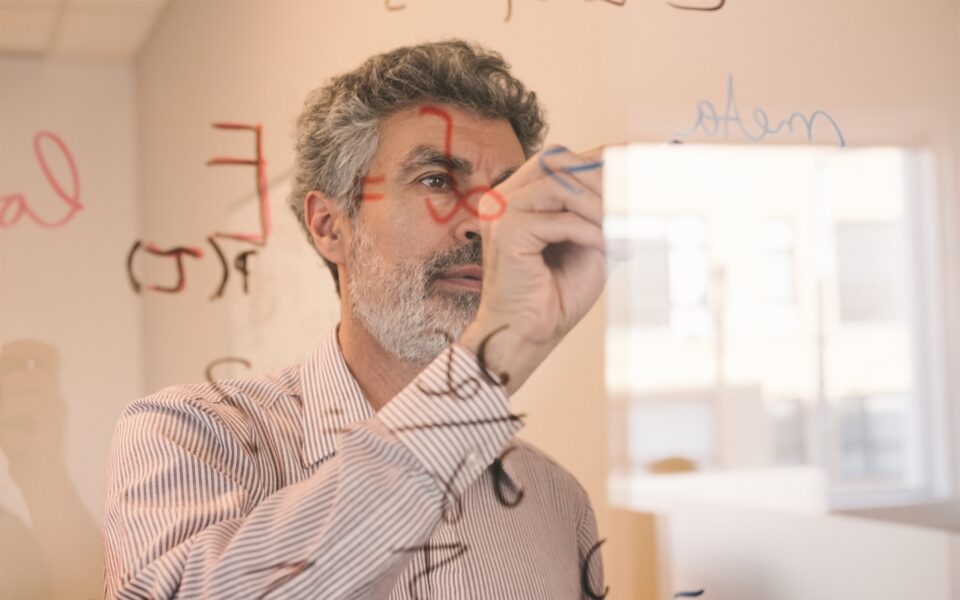

Canadian computer scientist Professor Yoshua Bengio, one of the ‘godfathers’ of machine learning, spells out the risks of AI to Kathimerini

Recently in the United States the case of a lawyer captured public attention, as he based his defense line on previous cases which, however, had not occurred. The lawyer admitted to receiving his references to these “nonexistent” cases through the use of artificial intelligence. This incident, along with others, alarmed the “fathers” of artificial intelligence, leading them to co-sign a second text prioritizing the risks posed by AI’s infiltration into our lives.

Yoshua Bengio, a professor at the Department of Computer Science and Operations Research at the University of Montreal and one of the three “godfathers” of AI, explains in an interview with Kathimerini why humans are at risk due to the rapid development of “intelligent” machines, how these machines are becoming smarter than humans, and which parameters need to be considered when drafting the regulatory framework for supervising companies operating in the field of artificial intelligence.

As part of the interview, we asked the artificial intelligence software ChatGPT about Professor Bengio’s scientific background. The response we received was that “throughout his career, Professor Bengio has received numerous prestigious awards, including the Turing Award, often referred to as the ‘Nobel Prize of Computing,’ for his fundamental contributions to deep learning,” while adding that “Professor Yoshua Bengio continues to shape the future of artificial intelligence, inspiring researchers, practitioners, and the broader community to unlock the vast potential of this transformative field.”

You are considered one of the pioneers in the development of artificial intelligence. What attracted your interest?

Around 1986, I was very much attracted by the research on neural networks, which was very marginal. The idea that there could be a few simple principles that could explain our own intelligence and also allow us to build intelligent machines, like the laws of physics for intelligence, was very interesting. Therefore, the idea that these laws could exist and that we could find them motivated me.

What are the key points that non-experts need to understand about how AI works and what risks should we warn them about?

First, they should know that the success that we have achieved in AI in the last few years has been thanks to the ability of machines to learn. We call that “machine learning.” We do not program those computers to do particular things or to react to new situations. Instead, we program them with learning procedures so that they can change their “neural weights,” which are like connections between artificial neurons. And so, what this means is that the abilities are not always as expected. A lot of the inspiration for that design came from human intelligence and human brains.

Now, for the second part of your question, what are the risks? The risks are that if we build very powerful systems, they could be exploited by humans in ways that could be very good or very bad. Just like any dual-use technology, the more powerful it is, the more dangerous it can be, but the more useful it can be also. So that is the first risk.

The main thing that I am concerned about is how these systems could destabilize democracies because they can understand language and they can use it to interact with us and potentially manipulate us, influence us, or make us change our political opinion. So that could be very dangerous. We do not fully see the details of how this can happen. Many people are discussing that we need regulatory legislation to protect us, for example, to force companies to show that some interaction is taking place with an AI system, not with a human, or that the content that you are seeing, video, text or sound, is coming from a machine.

The other risk that I am worried about, which is maybe slightly longer-term, is the loss of control; that is, we are designing these systems right now, but we cannot tell them to behave in particular ways. It is hard to make sure that they will not behave in ways that could be harmful to humans. And if we lose control they might start doing things that they want to do, and then they could act in ways that could be dangerous for humanity, especially if they become smarter than us. And they will likely be smarter than us because, as we know, we are machines. Our brains are machines, biological machines. And we make progress in understanding the principles of how our intelligence works. And we are going to continue making progress and develop principles that work for intelligent machines. Therefore, we know that it is possible to build machines at least as intelligent as us, but probably we can build machines that will be smarter than us.

‘If we lose control they might start doing things that they want to do, and then they could act in ways that could be dangerous for humanity, especially if they become smarter than us’

Right now, machines can read everything that humans have written. And no human can do that, right? So, they can have access to a quantity of data and learn from that large quantity which is much more than humans can manage.

Do you think machines could become wiser than humans?

They could become more intelligent. They are not yet, but in some aspects, they are, clearly, better than us already. Real wisdom requires an understanding of what is it to be human. And I do not think they have yet that understanding, but they can get there because they have read so much text that humans have written and this could come faster than we expected. So, if you had asked me a couple of years ago, I would say that it may take many decades. Now I am not so sure. It could be less than a decade. It could be just a few years.

From your experience, what does AI teach us about human barriers and human thinking?

These systems have been trained by reading tons and tons of texts, essentially, and sometimes images. And so, they are a mirror of the way humanity as a whole thinks, including the biases and incorrect views about the world. There are just repeating what they have read. But it is not just repeating word to word, actually, they can understand a kind of logical thinking. So, to an extent, we can analyze them as a way to analyze humans. However, they are also sometimes quite different from us because they operate not exactly on the same principles as biology. So, you can think of them as a kind of alien intelligence. Like a being from another planet. But at the same time, they are very much a mirror of us because they have been trained on our planet.

If you were in a position to impose a constitution of rules that would regulate the operating environment for artificial intelligence, what would be the basic rules?

We need a lot more documentation, transparency, audits and monitoring to keep track of how these systems are built. That is the first thing. Then, when these systems are going to be deployed, they need to be deployed in a way that respects some rules to protect the public. Many people have talked about how to reduce potential biases like racism or misogyny. One thing that I am worried about is that these systems could destabilize democracy. And for this, we want to make sure that we are going to have a rule that says when content that was generated by an AI is shown to a user, the user should see clearly that it was generated by AI. And there are technical ways of doing this, like by using what is called watermarking. To kind of identify this content is coming from AI.

What would be the possible developments of artificial intelligence in the post-ChatGPT era and what are we going to see in the next decade?

I think that one of the biggest challenges that many people are working on – including me – is how we make these systems more coherent, more reliable. To be able to reason through long chains of reasoning in a reliable way, while avoiding their tendency to what people call hallucinate, which means “false statements” with very strong confidence. It is what I call “confidently wrong,” and that is bad because it could lead to bad decisions if humans follow what the machine has proposed. So, if we compare machine to human cognition, we see that these systems are fairly good at imitating how our intuition works. So, these systems do not have a notion of truth. They are just imitating the style of writing of humans.

What area of interest would you advise your students to focus their attention on?

In three areas. The first one is how do we develop more applications for social good, healthcare, environment, education and social justice. There are not enough investments in these because it is not as important to the companies as social networks or recommender systems and on where companies are making the most money. Second, we need to better understand the gap between human intelligence and machine intelligence in order to build more reliable systems. And third, we need to do a lot more research on safety, meaning how do we design systems and policies, how do we change even maybe our economic system and how do we coordinate internationally to make sure we do not get catastrophic outcomes.