Finding peace in troubled waters

In documenting refugee trauma, a director obtains some relief for her own guilty conscience

At 17 Hanan has already managed to conquer one of her biggest fears: water. A Yazidi refugee from northern Iraq, she nearly drowned in 2015 when the overcrowded rubber dinghy she was in was swallowed by waves on the perilous crossing from Turkey to Greece. Five years later, now working as a swimming instructor in Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony, Hanan is teaching her younger brother the basics of strokes, before his memories of trauma rise to the surface.

“I came across a newspaper article which said that a large number of refugees drowned in public pools in Germany because they did not know how to swim,” Nele Dehnenkamp, a freelance documentary filmmaker, says during a Skype interview from her home in Berlin.

“I thought, so many people, particularly young children, cross the Mediterranean and they don’t know how to swim. It must be so horrific for them to overcome this fear,” she says, discussing her short documentary “Seahorse,” which is being screened at the ongoing Thessaloniki Documentary Festival (TDF23).

Dehnenkamp, who has a background in sociology, began researching community pools around the country that are tailored to refugees. That’s when she came across Hanan. With her graceful and collected demeanor, the wide-eyed girl with the long dark hair immediately stood out among her noisy peers, she recalls. Auspiciously, the girl was keen to open up about her experience.

“I did not have to convince her at all. Hanan has a very strong interest in telling her story because, for her, it’s a way of healing. Every time she tells the story, it gets a tiny little bit easier to do that,” the director says.

Brutally persecuted by Islamic State (ISIS) militants, thousands of Yazidis, an ancient religious minority, were forced to flee northern Iraq. Hanan, together with her grandmother, her mother and her five siblings, spent a year at various refugee camps in Turkey before landing on the island of Lesvos in the eastern Aegean. They managed to reunite with her father in Germany a few months later.

“Greece is very present in her memories, because when she saw the Greek shore, she knew she’d survive. This feeling of survival is in her very much tied to Greece,” the director says. “One of her biggest wishes is to actually return to the place that she first set foot on in Europe, and swim in the sea,” she says.

Hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees used Greece as their gateway to Europe in 2015 and 2016, until the European Union struck a deal with Turkey designed to stem the flow. Thousands have died on the crossing.

Trauma

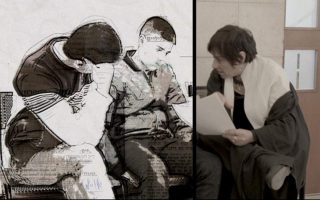

Survival and the challenges of assimilation are two of the themes that play strongly in the subtext of the 16-minute film, where Hanan and her young brother Sidar are seen communicating in German. The predominant ones, however, are memory and trauma.

“Trauma… there is a lot of horror tied to it, but also beauty,” Dehnenkamp says. “It comes from coping with trauma and managing to overcome it. It also lies in the pride Hanan takes in having been through all that and having learned how to swim,” she says.

The film’s title was originally inspired by Germany’s first swimming badge, Seepferdchen (Seahorse), which is recognized across the country as proof that a child can stay afloat in the water – like a seahorse. While researching the project, she found out that the part of the brain named after the Greek word for seahorse, hippocampus, because of its shape, is its memory center.

“It struck me that memories which are stored and archived in the hippocampus are usually tied to very strong emotions. Traumatic memories are connected to the amygdala, which is the area associated with fear in the brain. Extreme emotions, like the fear of drowning, are recalled more easily and they will most likely stick with you for the rest of your life,” she says.

Six years after Chancellor Angela Merkel’s famous statement “Wir schaffen das” (We will make it), which marked Germany’s open-door policy to refugees at the peak of the influx, Dehnenkamp is annoyed that most of her countrymen seem to understand the crisis as something that occurred in 2015 and is now over. “This is simply not true. For the people who crossed the sea, these memories will stick for the rest of their lives,” she says.

“This is, in a way, what I really wanted to show with this film: Going to a public pool in Germany to learn how to swim is the most everyday thing that you can do here. It’s what everybody does around the age of 6. But the child sitting right next to you may have a very good reason to be afraid to get into the water,” she says.

Germany took in around 1,000 Yazidi refugees under a special relocation program in 2014. It is now home to the largest Yazidi population outside of Iraq. According to a study published in 2019, almost 80% of Yazidi women in Germany said they had been raped by ISIS fighters; and half of them said they became pregnant as a result of rape.

Dehnenkamp says the country’s political class is mostly reluctant to acknowledge that the refugee crisis has had a long-term impact on German society. Doing so, she explains, would be recognizing the psychological trauma that many of the newcomers have endured.

“People have this idea that, ‘OK, you survived this life-threatening trip so you should be fine. You’re here, you’re safe.’ But it’s more complicated than that. And I think politicians have not yet taken that into account,” she says.

about social change,’ Berlin-based filmmaker Nele

Dehnenkamp says. [Dominique Brewing]

Empathy

In 2015, shocking images of Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi’s drowned body lying face down on a Turkish beach placed worldwide attention on the refugee crisis. The photograph also “haunted” her mind, Dehnenkamp says, describing it as one of the main events that galvanized her into action. Today, she is optimistic that projects like her documentary can have a similar effect on other people.

“I do believe that building empathy really helps bring about social change. I do hope that when people watch this film they will understand that an escape to Europe is not just a several-hour trip across the sea, but a lifelong challenge that you have to cope with,” she says.

“I cannot undo what she went through,” the filmmaker says of Hanan. However, she hopes that the documentary can serve as a platform for Hanan to tell her story. “She feels that all the ordeals she went through went unnoticed. And I don’t want her to feel that way,” Dehnenkamp says.

But the refugee girl is not the only one looking for healing, it seems. Dehnenkamp admits that watching the little boy Sidar, seen in the film hesitating in his orange floaties on the edge of the pool, gives her a feeling of guilt. “I feel guilty for letting [the refugee drama] happen as a European society,” she says. “It takes me back to the image of Alan Kurdi. Children are the most innocent beings out there; they should not have to go through all this,” she says.

Dehnenkamp says the traumatic memories currently hidden inside Sidar’s brain could well surface over time. “One day, he’ll probably ask, ‘Why did I have to go through all that?’” she says. “I have no answer to that. The least I can do is to document this and make sure it did not go unseen.”

Screening between March 4-14, the 23rd installment of the TDF has moved online due to the pandemic. For news and information, visit the festival website.

You can visit the film’s official website (in German), with details on Hanan’s journey to Germany, here.