Can housing become affordable again?

Old apartments are undergoing renovations and ground-floor commercial spaces are experiencing a shift in purpose. Formerly home to small businesses like grocery stores and office, they now accommodate cafes and art spaces. Key boxes for short-term rental units festoon entrances all over the city. The sound of visitors’ wheeled suitcases resonates from the sidewalks, yet public spaces remain unchanged, as our streets and public squares do not reflect the transformations occurring within the apartment blocks. Athens is undergoing an inside-out transformation, but the most significant changes are neither visible nor perceptible from the street; they involve the people.

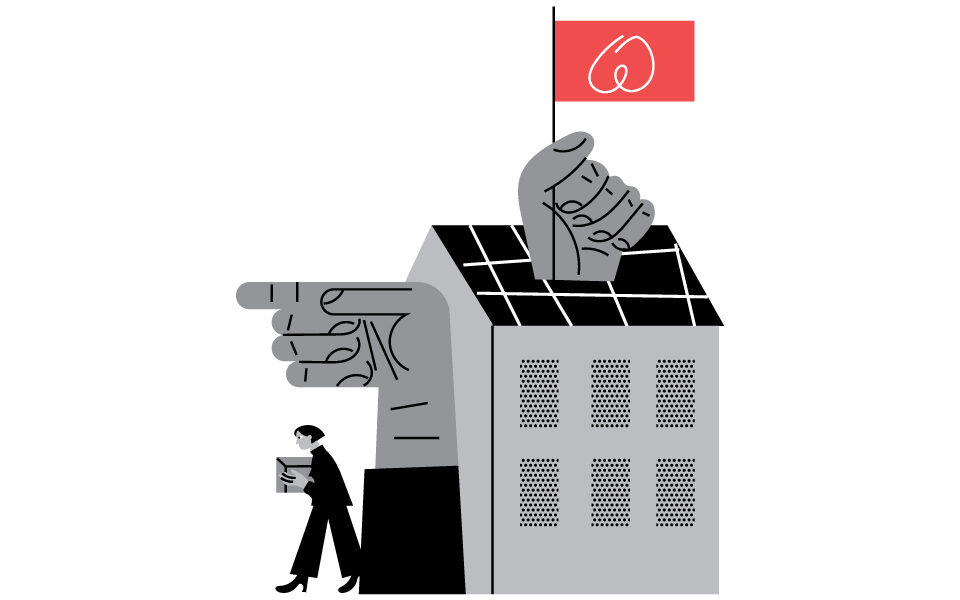

Downtown neighborhoods are experiencing the departure of many long-time residents. In their place, a diverse population from the Middle East, from China and from all over Europe is emerging, bringing a metropolitan character to the city center. Accompanying these new residents is a surge in tourism, which views the city as a consumable product. Airbnb has brought mass tourism directly into the “polykatoikia” (the building blocks that evolved in Athens in the 1950s), literally into the next-door apartment. However, this coexistence is neither harmonious nor advantageous for everyone.

Recent data from Eurostat reveals an extremely pressing social issue concealed behind the facades of Athens’ apartment buildings. Over the last four years, the cost of rent has surged by 40% and the average home sale price has skyrocketed by 70%. Simultaneously, the rate of homeownership is steadily declining, placing Greece in the 20th position among 33 European countries in the relevant table. The housing problem is prevalent in most European cities due to escalating construction costs and high interest rates, rendering construction investment unprofitable. In Greece, however, the problem is exacerbated by low wages. The cost of housing in Greece remains below the European average, making it an attractive investment for foreign buyers. However, given the fact that renting an apartment in the city center corresponds to an entire average salary, many are compelled to seek accommodation elsewhere.

The issue extends beyond the gradual displacement of the middle class from central neighborhoods; it encompasses the broader challenge of acquiring housing in Greek cities. This predicament predominantly affects younger residents, aged up to 34 years old, as, according to recent statistics, 72% of them still reside in their childhood rooms.

The postwar apartment was designed in accordance with the nuclear family model, which is no longer the sole model in contemporary times

The Athenian apartment building offered a solution to the huge housing problem in post-war Greece, addressing challenges much more formidable than those faced today. The “antiparochi” system (where old houses were exchanged for the right to apartments in newly constructed blocks) represented an intelligent collective initiative supported by the state to tackle the significant wave of internal migration. The polykatoikia that was the product of the antiparochi system not only provided housing for the new urban population but also facilitated the modernization of residential infrastructure and the dissemination of contemporary living standards. Can we come up with a comparable solution today to tackle the ongoing housing crisis? Could this crisis pave the way for the modernization of the apartment building typology?

The “Social Antiparochi” program that was recently unveiled by the government is a clever initiative aimed at creating social housing in state-owned properties. However, its effectiveness in providing ample incentives for the private sector to generate appealing residential units remains uncertain. Additionally, questions arise regarding the architectural aspects of the new apartment buildings. The postwar apartment was designed in accordance with the nuclear family model, which is no longer the sole model in contemporary times. It is time to contemplate how we envision living in 21st-century cities. The demand for new social housing in Greek cities presents an opportunity to explore innovative residential typologies that cater to diverse lifestyles and incorporate recent experiences, such as flat-sharing, the possibility of remote work or the conversion of rooms into shared recreational spaces. Alongside the conventional family apartment, novel cohabitation structures and the creation of imaginative shared spaces, like collective kitchens, should be considered. In times of crisis, such as the present one, it is the opportune moment to reconsider everything we had taken for granted and to plan for the future.

Panos Dragonas is an architect, curator and professor of architecture and urban design at the University of Patra.