Osama’s odyssey from Gaza, to Patissia, to Belgium

The journey of a 12-year-old boy from Palestine who found shelter, got an education, and put down ‘roots’ at a school in Athens

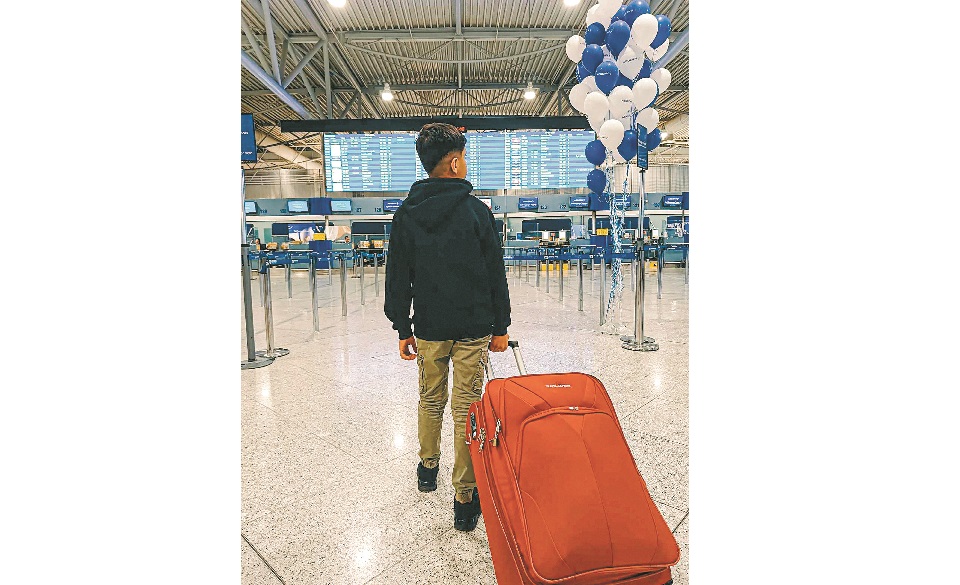

On the night of January 16, 12-year-old Osama from Palestine couldn’t sleep. Early the next day he would travel from Athens to Belgium to meet his big brother. He was excited to see him again after four years, but also nervous – about the trip, the new beginning there and of course the war back in his homeland.

When he left Palestine alone six months ago, Israel’s war in Gaza had not yet begun. Perhaps out of childish naivety, he felt that a wonderful adventure was about to begin. He had no second thoughts, nor had he felt fear. At the beginning of September, he had boarded a plane from Egypt to Turkey for the first time and from there he took a boat to the Greek islands. When, in the middle of the sea, someone shouted to him to throw his things overboard to lighten the boat, he did not object. He threw away his school bag, in which he had put a change of clothes. He only kept his documents and mobile phone. With it, he sent a message to his father that he had arrived safely on the small island of Leros, in the Dodecanese.

‘Our priority is not for a 12-year-old child, who does not speak a word of Greek, to learn language or history, but to feel good in the school environment’

At the local migrant camp he waited patiently for days for his case to be processed. On September 24 they put him in a coach. He didn’t know exactly what was going on. He was told he would go to a hostel in Athens – he just dutifully followed the instructions. The excitement he had felt a few weeks earlier was gone. Inside the boat, he did not feel well. It was dark and there was bad weather. He vomited and developed a fever. The journey seemed endless to him. When he arrived at the hostel of The Home Project – an NGO that supports unaccompanied refugee children – at midnight, he was exhausted. One of the staff at the NGO hugged him and he started crying. The next morning he ate breakfast, but was taciturn and timid. Due to the hardships he had endured, he looked younger – and that was something he felt himself. He suddenly missed his family and sought the care of the group at the hostel.

When he met Mr Yiannis, the interpreter, and the other children who spoke Arabic, Osama cheered up. His spirits also improved when he saw a school courtyard from a window. He knew that the process of reunification with his brother had begun and it was only a matter of time before he left Greece, but he wanted to go to school in Athens. Back in Palestine, he told the carers, he loved his school. Although his life had always been difficult – he had lost his mother when he was young and there were frequent conflicts in the area where he lived – he preferred to talk about the good things at the hostel: that every two days they went to the sea or that he was really good at roller blading. His father was a doctor’s driver who commuted daily between Egypt and Gaza. In the summer, having collected the money for the trip, his father decided to send Osama to his brother in Europe, in the hope that he would have a better future.

He started at the Greek school in early October. The teacher told him to sit next to Melek and Violetta, who spoke Arabic. A teacher who had studied theater and also spoke Arabic started teaching theater improvisation. “Our priority is not a 12-year-old child, who does not speak a word of Greek, to learn language or history, but to feel good in the school environment,” explains school principal Konstantina Bozonelou. At the school in Kato Patissia, where she took over in September, as well as in the previous one, nearby, where she worked as a teacher, 70% of the pupils are either children who have recently arrived in the country or children of second-generation immigrants, most of whom do not speak Greek properly.

The process of integrating them into school is not easy. “At our school we try and do everything we can to educate ourselves as teachers. Because we also feel awkward about this new profile of the school,” she explains. All of the teachers now attend inclusion programs for dealing with children from different cultural backgrounds.

A few days after Osama started school, the NGO had one more difficulty to manage. The war in his homeland. They saw him communicating with his father and waited for him to initiate a conversation on the matter. He opened up after a few days. His village, he told them, is on the border with Egypt. Although it was not the focus of Israel’s bombing campaign, there was danger. “But my dad is very careful and he’ll be fine,” he told them.

Those left behind

At school, Osama’s arrival was the occasion for an important discussion. How he left his homeland and what those who have stayed behind experience. In the following weeks he was seen increasingly restless and always with mobile phone in hand, longing and anxious to communicate with his father, who now rarely had access to the internet. “We see the devastating effects on our children coming from war-torn countries. Children who faint because of the trauma. We see how it destroys lives, entire generations,” notes Sofia Kouvelaki, CEO of The Home Project.

The staff at the hostel tried to support Osama in every way they could and saw how he, too, found refuge at school, in his new friends and in the various programs of The Home Project. He chose to spend his weekends at ACS and the Athens College, where he attended lessons and engaged in sports activities with other children from the hostel.

When the green light was given for the reunification with his brother in Belgium, the school wanted to organize a farewell celebration. But Osama suddenly refused to go to school. The reason, they understood, was that another farewell was difficult for him. They explained to him that a beautiful circle was closing and that his friends and teachers also needed to say goodbye. He returned to school and when his classmates revealed that they were going to throw him a party, he was excited. That day he put on his favorite clothes, borrowed cologne from an older boy at the hostel and gelled his hair.

In the school yard, they all joined in to plant an olive tree – Osama’s olive tree. “We will make sure it takes root and your little tree will grow to blossom and bear fruit. We will be sending you photos and we want you to send us photos too, to see you growing and progressing,” the school principal told him. “It will be a link to the place where you lived, even if only for a little while, and whenever you come back, you can stop by and see it. We planted it on purpose in this corner so that it can be seen through the barred door.”

His classmates hugged him and all together shouted his name. Osama, looking happy and moved, told them that he had another olive tree in the garden of his house in Palestine, which was at least 100 years old, with a huge trunk. The souvenir they gave him, a photo of all the children and staff glued on a card with wishes from everyone, he took with him to Belgium.

When he arrived at his new home it was the first thing he took out of his suitcase. He wanted to hang it in his new room.